Following on from last week’s introduction, we’re now going to have a look at how the drink is made.

The production of Sherry is fairly technical so what follows is a very simplified version of events, if you can believe it. If you happen to be writing your thesis on the matter and are after more detail, Julian Jeff’s brilliant “Sherry”, in print since 1961 and now in its 5th edition, is well worth a look (www.sherry.wine).

The Palomino Fino grapes are harvested in early September. Once they’ve been removed from their stems and pressed to separate the liquid from the skins, the resulting juice is fermented quickly at a relatively warm, controlled temperature in stainless steel tanks to produce a neutral, dry base wine with around 11% – 12% alcohol.

Once the fermentation of the must has finished and the nascent wine has been clarified it is fortified with a very, very alcoholic grape brandy mixed with an equal proportion of base wine so as not to “shock” it. The level of alcohol the wine is fortified to depends on the wine that is being made. If the winemaker is looking to make a wine that ages under a layer of yeast (flor) such as a Fino, the base wine is fortified to around 15% alcohol as this is the alcoholic strength at which the flor is happiest. If he or she is after an Oloroso, a wholly oxidative style, the wine is fortified to at least 17% which prevents the flor from growing and therefore the oxygen is free to attack the wine with gay abandon from the start.

We will look at the different styles of bottled Sherry next week but it’s worth mentioning here that they are made from two different styles of base wine that come from the same grape and are made in a similar way. Sherries such as Fino and Amontillado are made from fino base wine (note the small “f” to differentiate it from the bottled version) which in turn is made from grapes from older vines grown on the best Albariza soils. They are pressed gently, if at all, to yield a pure, elegant, free-run juice, low in impurities. The first press, if you like. Olorosos, in contrast, are made from oloroso base wine produced from the fruit of younger vines which grow on heavier, clay based soils and they will be pressed with more force to produce a coarser product with a higher level of impurities, body and astringency. This isn’t to say Olorosos are therefore inherently inferior to Finos and Amontillados, just different. A winemaker certainly wouldn’t be able to make a great Fino from the oloroso juice but a true Oloroso couldn’t be made from the gentle pressings intended for Finos.

Whatever style is being produced, the finished base wine is now ready for ageing and blending…

The Solera System

Now, if you’re a cork dork, this is where it gets interesting. One of the keys to the production of Sherry is the Solera system of maturation and blending. Sherry wasn’t always made this way. It basically came about in order to ensure consistency. This system isn’t unique to Sherry and not all the wines are made this way but the vast majority are and it’s worth examining before looking at the different styles of bottled Sherries next week.

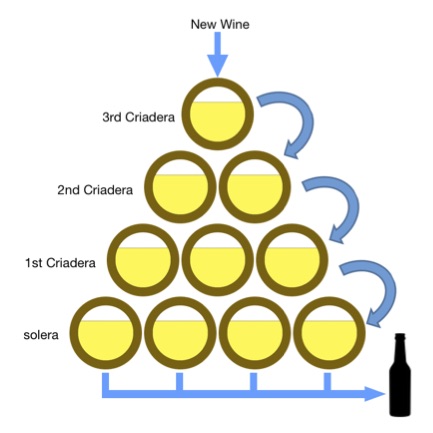

For the sake of clarity examine the two-dimensional pyramid of Sherry casks above, all filled to around 5/6 capacity. The reason for leaving this ullage in barrel will become but in a nutshell it allows the layer of flor to “breathe” and thrive on the styles of Sherry that require it and for sufficient oxygenation to occur when producing wines that are aged oxidatively.

Real Soleras don’t look quite like this and the different barrels may even be kept in separate bodegas. They usually comprise of 3 or 4 layers (known as criaderas) but more complex Soleras can have as many as 15. Wine from the bottom criadera, confusingly also referred to as a solera (note the small ‘s’), is where the wine for bottling is drawn from. The casks are never completely emptied and once the bottling has taken place the 1st criadera is replenished with wine from the 2nd criadera which in turn is refilled with the next level up and so on. The criadera at the top of the system is refreshed with new wine. This process is known as “running the scales” and its frequency depends on what wine the producer is trying to make with Finos requiring the most regular refreshment in order to maintain the flor.

This system is integral to Sherry production because it enables consistency with all those wines being blended together and keeps the wines fresh. Without the introduction of younger wines, Amontillados and Olorosos would become too concentrated, astringent and ultimately unbalanced. When making a Fino Sherry the process enables the flor to survive by replenishing the nutrients it needs allowing it continue imparting its flavours and protecting the wine from oxygenation which is not desired in this style of Sherry.

Claro? Good. As mentioned, next time we’ll be getting into the different styles of dry Sherry, what foods to pair with them and some recommendations to try. In the meantime feel free to get in touch with any comments or questions you might have. Emails can be sent to the address in the bio below.

Photo credit: Pexels