For the past several years, without fail, various trade magazines, in partnership with some think-tank or another, have boldly predicted the coming 12 months to be “The Year of Sherry”. They point to Majestic Wine recording a 25% increase in sales, the bastardisation of the wine with pop in order to appeal to hen-dos and the opening of numerous trendy tapas restaurants in Shoreditch as sure fire evidence of this. It never comes to pass. But it definitely will next year.

Poor Sherry. The fortified white wine of Andalucía, has had a torrid time of it for the past 30 years. Ask most people with a passing interest in wine what they think of it and they’ll tell you it’s the cheap, sweet tipple of little old ladies, tramps and Uncle Monty from Withnail and I, best drunk from a glass thimble. Harvey’s Bristol Cream and Croft’s Original are largely responsible for this.

Source: DO Jerez y Manzanilla

Perhaps this is in part due to the fact industry insiders, who pride themselves on liking things no one else does, simply can’t believe a wine of such high quality, offered at such extraordinary value can continue to be so underappreciated (cf. Riesling).

They’ll point to its versatility as a food wine, its length, consistency, uniqueness and how it’s always released ready to drink. Styles other than Fino and Manzanilla can also be left open for days if not weeks without losing their freshness and are therefore ideal for drinking a couple of glasses at a time.

The problem is, like so many of the best things in life, Sherry is, particularly in its driest expressions and even more so when biologically aged, an acquired taste. In my experience, handing a glass of Fino as a pre-dinner heart-starter to a guest hoping for the usual Marlborough Sauvignon Blanc or Pinot Grigio can be like offering a bowl of anchovies to a teenager weaned on Haribo Starmix.

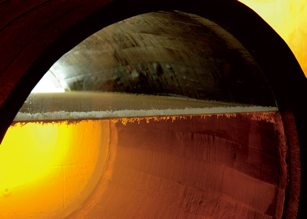

Before I became a fully paid-up member of the wine-plonker fraternity, I never gave Sherry much thought. Why drink something ostensibly so demanding when you can guzzle a lovely sweet fruited Shiraz from McLaren Vale? Basically, to someone without any experience of Fino Sherry especially, it just doesn’t smell right. The ageing of the wine under a film of yeast or flor (picture below) contributes to its characteristic aroma, in part due to high levels of the chemical compound acetaldehyde, which would be seen as a fault in most other styles of wine.

Sherry covered in a layer of flor. Source: DO Jerez y Manzanilla

Studying Sherry under the tutelage of an obsessive, I became besotted with the drink and that is down not only to his infectious passion but also an understanding of how and why Sherry tastes the way it does. Once we get past our initial distrust of it and are able to appreciate it for what it is, a world of affordable pleasure awaits!

It should be noted that the mere act of drinking Sherry makes you cleverer, cooler and suaver than everyone else. Despite being Spanish it’s the quintessential choice of old-school British sophistication. I’ve also never met a Sherry lover who wasn’t a thoroughly good egg.

There is a lot of exciting stuff going on in the Sherry region, from unfortified flor-aged whites, unfortified red wines, single vineyard bottlings and vintage expressions.

Over the next two weeks however, we’ll look at the traditional, dry and what I like to think of as true styles of Sherry, where they come from, how they’re made and what to eat them with. But first, a bit of history…

A potted history of Sherry

The town of Jerez in South West Spain is thought to have been founded by the wine-loving Phoenicians in around 1100 BC, then the Carthaginians had a pop at it and then the Romans. Those Romans, who loved a drink and had a habit of turning every corner of their empire into one big vineyard, set about making huge advancements in viticulture here. By the time the Moors rocked up in 711 AD the winemaking culture of Jerez (by this point called Seris) was in full swing and the conquering Muslims did little to curtail the locals’ passion for boozing. Then came the Christians who cranked production up still further and trade with France and England began towards the end of the C15th. By this time, many of the wine merchants were Englishmen who in true Anglo-Saxon style introduced production rules and established quality standards.

The English and Spanish weren’t getting on very well throughout the C16th for obvious reasons – the former had begun establishing theme pubs and Indian restaurants in Cadiz. Under orders from the court of Elizabeth I, English Privateers such as Drake raided Spanish ports, plundering huge quantities of wine from the region and it was this bounty that helped forge the initial popularity of Sherry in England.

Source: DO Jerez y Manzanilla

Despite continued setbacks, mostly on the back of subsequent Anglo-Spanish wars with a bit of Phylloxera thrown in for good measure, the industry continued to grow and by the mid-to-late C19th was booming. In order to keep up with demand, products were cut with inferior plonk from outside the region. This, allied to a price war and the proliferation of imitation New World “Sherry”, saw its reputation and demand in Victorian Britain and Holland drop dramatically.

Shortly before World War I the Sherry Shippers Association embarked on a marketing program which saw Sherry’s fortunes revived before the market collapsed again in the face of World War II.

An upturn in popularity in the UK, fuelled by styles such as Harvey’s Bristol Cream, was followed by yet another period of price-cutting initiated by the Rumasa group. Rumasa had borrowed huge amounts of money from the banks to buy up swathes of bodegas in the 1960s in order to supply Harvey’s and they went bust in the 1980s sending the region into another downward spiral.

However, Sherry seems to have finally learnt its lesson. Vineyard areas and stocks have been dramatically reduced as the market has acted to bring supply in line with demand. Quality, not quantity, is now the watchword of winemakers and the introduction of very high end, limited production wines as well as clever marketing has helped improve the category’s reputation markedly. Producers such a Tradicón and Equipo Navazos have bought up old Soleras and even single barrels from defunct bodegas in order to bring them to market and showcase their unique quality. Products of such an extraordinarily high standard have earnt rave reviews from critics which has translated to an increase in demand from consumers.

The premium end of the market is now focused on authentic, dry expressions as the region recognises the floundering fortunes of sweeter styles of wine. Quality has never been higher and this, allied to the remarkable value they offer and clever management from the regulators may just see this category thrive once more. In short, there has never been a better time to drink Sherry.

Next time we’ll get nerdy as we take a look at where Sherry comes from and how it’s made.