Inflation is running hot, even before wage-price pressures have begun.

Central bankers tell us the current burst of inflation will be transitory and workers will not mind the temporary squeeze on their living standards.

In today’s full employment economy, this is not convincing. The implied policy response is flawed, potentially even reckless.

The US inflation rate is at a 40 year high (US Bureau of Labor Statistics). The Bank of England forecasts UK CPI inflation will hit 7.25% this spring, by far the biggest inflation overshoot since the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) was created in 1997 (Bank of England (Feb 2022), Monetary Policy Report).

We are told not to worry. The current inflation burst is transitory. Policymakers cite two reasons for this: first, because the energy shock will hurt demand (it will lower inflation) more than it lifts firms’ costs. And second, because supply chain bottlenecks, driven exclusively by the pandemic, will be resolved swiftly as health risks subside. This perspective has never felt convincing. And the scale and persistence of the inflation spike has made it increasingly untenable.

The problem is that monetary policy remains exceptionally accommodative. Central bankers are so far down the rabbit hole, and markets so anchored to the belief in persistently low interest rates, there is no obvious way out. To keep a lid on inflation, economies need materially higher real interest rates; but what they need, financial markets cannot tolerate.

Central bankers disagree. In their eyes, inflation can be contained while keeping real interest rates (inflation-adjusted interest rates) at or below zero. They claim the background environment remains structurally disinflationary (China, globalisation, digital technologies, demographics, etc) and the economy is sufficiently flexible, so a wage-price spiral won’t emerge, as it did in the 1970s. If evidence emerges that suggests otherwise, then policymakers assure us they have the tools to manage the problem without undue economic disruption.

“Critically, the inflation threat is greatest in the country that matters most for global financial markets, the US”

At a minimum, this view appears cavalier. Economies are facing multi-decade highs in inflation, yet the policy accelerator remains flat-to-the-metal and labour markets are red hot (Atlanta Federal Reserve). Critically, the inflation threat is greatest in the country that matters most for global financial markets, the US.

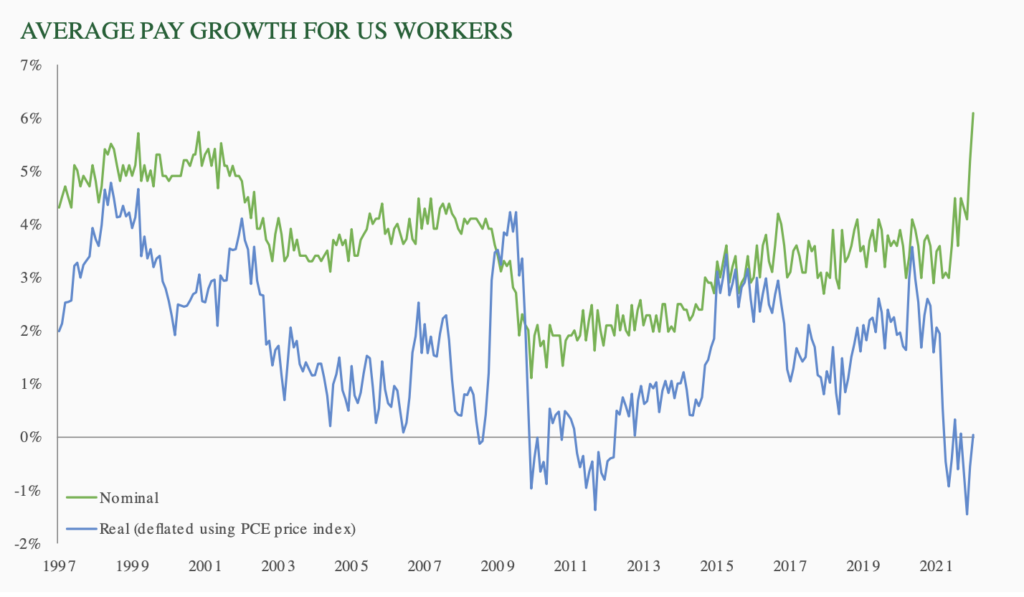

This chart shows workers face a potentially sizeable hit to their real (ie, inflation-adjusted) income at a moment in history when they, in fact, have the upper hand (Atlanta Federal Reserve Wage Tracker, BEA). While trade unions may be a spent force, those in work seem more than willing to resist the cost-of-living squeeze now underway by demanding higher wages.

Economic history tells us that ‘cost-push’ shocks fizzle out most of the time. But whether they do is contingent on the circumstances in which they strike and the response of policy to them. If workers are able to resist the squeeze to their earnings, fears of a wage-price spiral may quickly become a reality.

Recent developments in Ukraine remind us the future is unknowable. But the inflation regime is clearly changing: higher and more volatile inflation is already with us.

What one can say is current asset prices do not reflect this risk. The rules of the game for investors are changing and portfolios anchored to a belief in transitory inflation are dangerously exposed.

Originally published by ruffer.co.uk and reprinted here with permission.