What Blackstone’s recent US housing deals tell us.

In late June 2021, Blackstone acquired Home Partners of America Inc (HPA), a company owning roughly 17,000 single-family homes across the US, which is as much of a rent escalation play as it is underwriting capital value appreciations.

This week, Blackstone expanded its US housing footprint by shelling out $5.1b to take over a portfolio of 678 rent-controlled housing communities from AIG across major metropolitan areas. The idea here is obviously to capitalise on the expectation of political support for expanded federally funded low-income housing tax credits, while keeping an eye on potential rent escalations once grace periods end.

Now, what are the parallels to sub-Saharan African markets? Well, the HPA deal, albeit an interesting blueprint to boost home ownership among the emerging middle-class in SSA, will be a tough one to replicate. That’s primarily due to the lack of functioning (mortgage) capital markets, in-flux land registers and title deeds, as well as the generally short-term view of SSA investors.

The second transactions, though, targeting the low-income housing market and in particular its taxpayer-induced risk backstops, is an interesting one.

How does the federal US rent-control scheme work? In a nutshell, it provides (dollar-for-dollar) federal tax credits for investments made in rental units with rents of max 20% of the local median income. Given the progressive nature of most tax systems, that obviously provides arbitrage opportunities for investors.

The idea, while not always enjoying bi-partisan support, is an interesting mechanism that cuts to the core of the low-income housing issue: affordability.

Ensuring affordability of housing is on the political agenda of pretty much every western society today, as it is in sub-Saharan Africa. The main difference is magnitude.

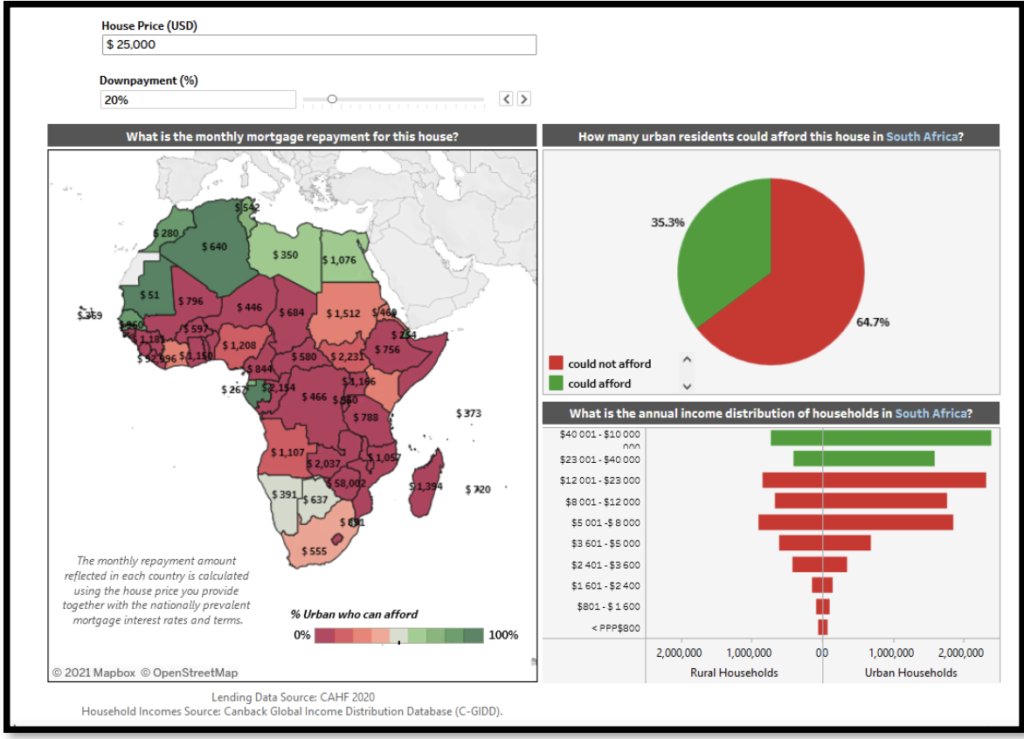

Let’s take a look at South Africa, the continent’s most developed and industrialised country, to get a sense for the issue. The calculation is based on the lowest-cost house at $25k available in the 2019 market, as reported by the Centre for Affordable Housing Finance in Africa, an independent think tank.

What does it tell us? Despite the fact that South Africa has relatively well-developed capital markets, efficient construction and developer businesses and material procurement, only 1 in 3 urban households can afford the cheapest house available.

How can this be tackled for the remaining two-thirds? South Africa chose an interesting, albeit somewhat unique route partially applicable to other sub-Saharan countries.

Following the end of apartheid in 1994, the Reconstruction and Development Program (RDP), a set of socio-economic measures to alleviate poverty, especially among the disadvantaged black population, was put in place. The programme’s measures, geared towards the provision of basic needs, also included an allocation of $2-3b annually to provide free basic houses (so-called RDP houses) available to families earning a maximum of $3,000 pa. This roughly covers the four lowest income brackets in the graph above.

What about families earning too much to be eligible for free (RDP) housing, but too little to qualify for a mortgage, the so-called ‘gap’ or ‘affordable’ market?

Through its Department of Human Settlement, SA implemented another programme, FLISP (Finance Linked Individual Subsidy Program) for families with an annual income of max ZAR 180k (PPP$ 26.4k) which gets close to the affordability threshold of roughly PPP$ 33k shown above. The one-off FLISP support of ZAR 87k (PPP$ 12.7k) can be used to support financing a property costing up to ZAR 300k (PPP$ 44k), which appears to be inline with general market prices.

What lessons does this hold for other SSA countries?

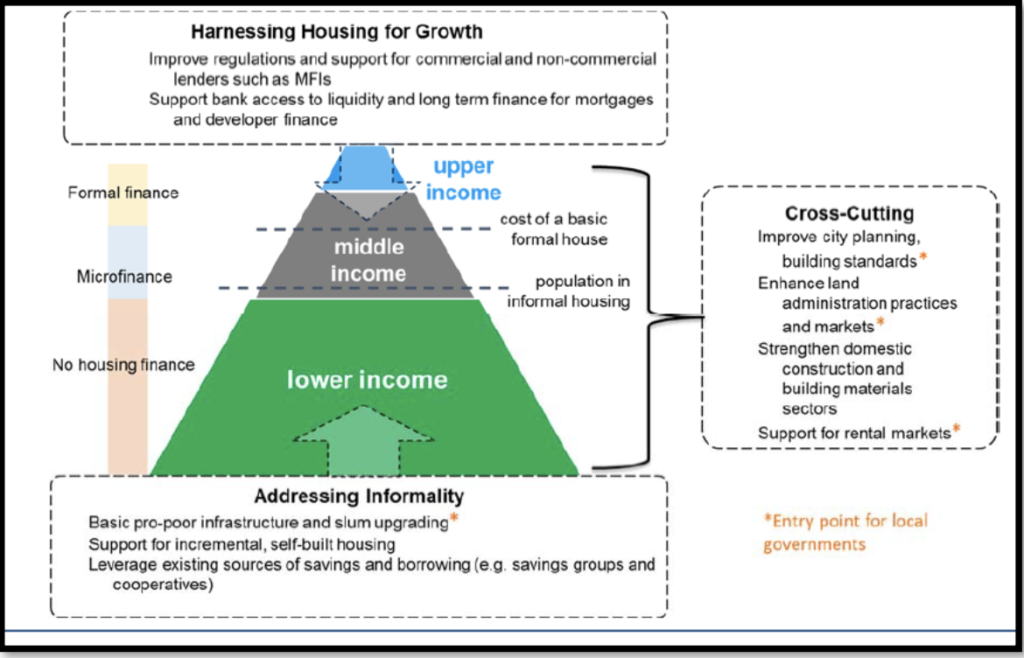

There’s no ‘one-size-fits-all’ solution. Different socio-economic groups will require different measures. While direct government intervention using large scale, low-cost development programmes will be needed to alleviate the short-term pressure caused by rapid urbanisation, additional interventions are required to cover the gap/affordable sector. That’s especially relevant given the absence of accessible and affordable private mortgage finance in most SSA markets.

Providing direct financial support like in the case of SA is one avenue, tax credits for developers like in the case of Kenya is another one, as are risk backstops provided by international development agencies. Examples include the recent $36M CDC investment in South Africa’s DiverCity platform or UNOPS’ massive partnership with the Guinean government to deliver 200,000 low-cost housing units with a total project volume of $8b.

Apart from financing solutions, another important element is increased transparency at the planning and zoning stage, primarily driven by digitisation.

Equally important are efficiency improvements in material procurement (nearshoring and domestic production along with enhanced trade – AfCFTA is a good start) to reduce overall construction costs. The following graph compiled in 2015 by World Bank analysts provides a helpful visualisation of the necessary action items required to improve access to quality affordable housing.

How much time do we have? Very little. The sub-Saharan region is urbanising at breakneck speed. At the same time, population growth in almost all SSA countries adds to the urgency.

But there is more.

Apart from putting a roof over people’s heads as an essential requirement, especially for the younger generation to lead a productive and fulfilled life, it also helps rapidly ageing societies outside of sub-Saharan Africa, as the regions’ demographic dividend has the potential to offset deficiencies elsewhere.

A happy home is more than a roof over your head, it’s a foundation under your feet. (Amish Proverb)

We are currently seeing several promising low cost, large-scale residential and ancillary projects in SSA offering significant impact investment opportunities at-scale along with attractive returns. If you would like to learn more, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.