It’s 2020 and YYY’s value-add fund is in acquisition mode.

The target return is set at 13%, and the manager presents a deal; a three-year business plan with 60% leverage and a CapEx budget of 40% of the capital value. The location? An emerging area in Hamburg, with a yield offering a 25bps premium over the city’s CBD.

The plan relies on this CapEx to drive rents up by 40%, yields to compress by another 25bps, driven by capex, and a quick exit in three years.

Projected IRR: 13.03% and equity multiple at 1.4x.

I don’t know about you, but my first reaction is that a lot has to go right for this deal to work. CapEx is 40% of the property’s value; what if construction costs rise? Yield compression in Hamburg where yields are sub 3%? A three-year business plan? What if there are no buyers at that level?

This deal involves CapEx risk, location risk, liquidity risk, leverage and macroeconomic risk. And the manager is not getting a bargain either at 25bps above prime yield! Risk taking in a deal like this is really expensive.

This is typical of a late-cycle deal run by an overly optimistic―or under-pressure-to-deploy―manager. And while this example is hypothetical, it wouldn’t be far from reality to say that deals like these often end up with returns well below zero. Stories like this reveal why it’s critical to understand different types of real estate risk and recognize when each is priced attractively, or not.

Over the course of two real estate cycles―yes, I am still young, and I intend to work well into my 80s―I’ve noticed that risk-taking follows a predictable pattern: early after a downturn, investors are risk averse and tend to keep risk low and focus on assets that seem core. Higher-risk deals are often sidelined. “Too risky”, “Location is not core”, “CapEx is too high”, “Lease is too short”, “It’s in a ‘B-city’”.

As the market begins to stabilize, investor sentiment shifts, liquidity rises, and pricing becomes keener. Then, the curse of the target return kicks in. “It needs to be 13%”, “We need more debt”, “A slightly quirkier location will have to do”, “Add some rental growth to the underwriting, please” are typical comments.

Finally, late in the cycle, confidence can transform into boldness, and investors stretch for high returns by pushing aggressive assumptions. “We need to deploy the capital, otherwise investors will not be happy,” cries the CEO.

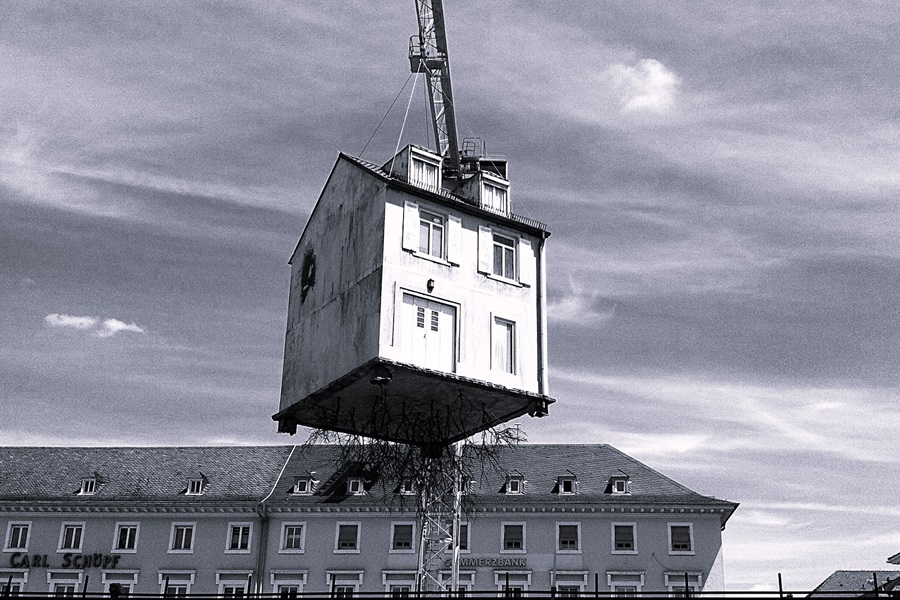

An example of this is the trend of three-year office repositioning plans at the top of the last cycle, where investors compressed timelines, increased leverage, assumed favourable yields, and so on…

It is for this reason that risk has become my bugbear. And it is for this reason that I am a co-founder of Evonite. Risk needs to be at the forefront of underwriting. How can you be in value add if you cannot measure, or at least score the risk of each deal?

The key question isn’t whether to take on risk; it’s about which risks to take and when, and at what price. Some risks—when priced correctly—present a high potential for return.

Development risk, for instance, can come at a bargain when the gap between development and investment yields is wide enough. Geneva offices in 2013 serves as a classic example: office development yields hovered around 9% while office investment yields were closer to 4%. You could go speculative; the “margin of safety” was so big that it made sense to take the risk.

Similarly, leasing risk is attractive when short leases are undervalued relative to long-term leases. A retail park in Leipzig in 2012 shows how this can play out. A simple lease renewal and re-tenanting of a difficult unit can change the yield from circa 7% to circa 5.5%, give or take.

CapEx risk is another classic. In periods of uncertainty many are not willing to take on improvement costs. But it tends to be in those periods where the cost becomes attractive.

Location risk is another one. Berlin’s Kreuzberg and Friedrichshain neighbourhoods in 2014 were about to take off as attractive office locations. Office rents were low―a massive discount to CBD, but the areas were cool and tenants were moving in. Demand was on the rise.

And then there is liquidity risk, the most important of all, which should be the subject of another article in itself.

With these types of risk in mind, it’s clear that value-add investments aren’t just about taking on CapEx and high leverage. Value-add strategies are about capitalising on risk that’s temporarily mispriced by the market. Other people call this “value investing”: buy low when perceived risk is high, and therefore risk is cheap.

Value add can also be about growth: capture income growth by responding to demand dynamics in rental markets Other people call this “growth investing”.

The art of real estate investing lies in knowing when risk is priced attractively. Development risk in Geneva offices, leasing risk in Leipzig retail parks, location risk in Berlin’s Kreuzberg are all examples where a keen investor could find opportunities where others might see challenges.

By understanding cycles, identifying “cheap” risks, and recognising when the market is shifting from boldness to overconfidence, investors can make decisions that stand the test of time. If there’s one thing past cycles have shown, it’s that disciplined risk-taking, paired with a strong grasp of market dynamics, is essential for long-term real estate success.