REITs are becoming what they always should have been: low-leveraged balance sheets and long-term income streams with a sustainable, growing dividend

Three features stand out for me in the quoted property sector this year. First, the catastrophic but entirely predictable demise of retail, where the valuation profession has finally recognised the reality of the situation. Second, the number of senior REIT executive directors who have decided to ‘retire’. And third, the spread of share price performance between the winners and the losers. They may all be interconnected to varying degrees, but speculating on why senior managers are exiting is not for me to comment on – publicly, at least – so I will start with the share performance.

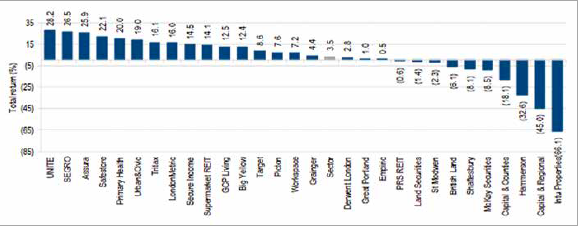

It really is extraordinary, but all those REITs to the left side of the chart in figure 1 trade at premiums to their NAVs and therefore have equity issuance as a currency and some have been using it to good effect. Unite is in the process of a transformative deal to buy Liberty Living, Primary Health used its paper to buy quoted rival MedicX, and LondonMetric used paper in part to acquire A&J Mucklow. All acquirers’ shares went better on the announcements and in the after-market; in other words, the equity market will happily support the right deal and accept premium, i.e. ‘expensive’ paper. More relevant is the fact

Figure 1: REIT performance Year-to-date

that all the REITs, with the arguable exception of Segro, Tritax and LMP, operate in the ‘alternative’ asset classes such as student accommodation, healthcare, self-storage, or long-income. The arguable exception bit refers to the fact that until perhaps this decade sheds were almost an alternative sector too, having underperformed seemingly forever, but then the rise of e-commerce meant simple sheds were replaced by state-of-the-art logistics.

Languishing to the right of the chart are not just those REITs that own retail but, soberingly for management teams, the four that used to be the sector leaders by market capitalisation: namely Landsec, British Land, Hammerson and Intu. Two have lost their chief execs or are about to, two have lost their heads of retail, and two have lost their finance directors – although one of those FDs has picked up the poisoned chalice of becoming Intu’s chief executive. After its acquisition of Liberty Living, Unite will become the UK sector’s fourth-largest REIT, with a market cap of about £3.7bn; Intu’s market cap is currently sub £500m and falling. Five years ago it was the other way round.

Half of direct property investment in the UK last year went into so-called ‘alternatives’, in spite of a healthy London office investment market – although overseas interest here has waned notably this year. Barely any money went into retail. Out with the old and in with the new is an understatement. The boards of the former large-cap companies did not grasp the scale of the impending collapse of retail – which, given they are the experts on the sector, is pretty remiss really.

For more than four years I have proffered the argument that yields were way too low and rents too high. For what it’s worth, I think so-called prime retail yields will rise by 200bps from about 4% to about 6%, which takes a third off values, while rents will fall by at least 25%, possibly more, which would halve the capital value. Too aggressive? I don’t think so. After tentative write-downs in 2018, Intu’s valuers took a broad-stroke 8-12% off its UK assets in the six months to June. There was little obvious difference in the capital performance of the ‘trophy’ Trafford Centre or Lakeside and the tail of smaller centres that it desperately needs to sell. Those two centres have dropped about 20% in value over just 18 months. Oh, and estimated rental values were down 7% to boot. Initial yields are still below 6% – but wait until rents rebase at lease expiry over the next several years. Debt covenants are being tested and will almost certainly be breached. As a colleague said, the only stable thing about Intu’s numbers is the dividend – which was maintained at zero.

Companies talk about “when the market stabilises”, but the e-commerce revolution shows no sign of slowing – just ask the shed landlords about that – and the major shopping centres need to evolve to reflect the fact that these centres simply won’t revert to what they used to be. Some faint hope may be at hand, however. By definition the big shopping centres are well located and often, though not always, in city centres. It is potentially valuable land, but perhaps more valuable for uses other than retail. I’ve never envisaged tumbleweed blowing through them – far from it – but they are probably too big, which may be a perverse positive, and they have a lot of land around some of them.

The only problem is that the quoted owners have scant capital resources to fund the requisite changes, although they are at least embracing the notion. Their eyes are firmly focused on reducing their debt burden by trying to sell assets into a virtually non-existent marketplace to try to contain the rise in their LTVs. Rock and a hard place. Also, their traditional ‘skills’ are in retail, even if they didn’t see its demise coming, but at least they will have the land value as equity, should alternative uses become inevitable. Perverse though this is, it’s the alternative sectors the retail landlords are focusing on as a potential panacea. Yup, guess what: they are looking at student accommodation, medical centres, the private rented sector, shared workspaces, and build-to-rent to be developed around (and indeed above) their centres.

So, we go back to the chart above. Our stock recommendations haven’t changed much for the last few years, and those recommendations have been anathema to all that has happened over the last many years. You buy the expensive shares and you sell the cheap ones! Buyers to the left, sellers to the right. Unheard of, but it’s been spot on and will almost certainly remain that way, because I can’t yet see what stops these sectoral trends continuing. Retail is in rental and valuation freefall, with grappling hooks

in short supply, while London offices are seeing stronger-than-expected tenant demand with no worrying level of oversupply (or indeed leverage) but very limited evidence of rental growth and currently weaker investment demand. The two major asset classes of the REIT sector for all of my career offer few positives at the moment and perhaps for a goodly while ahead.

It is likely that we will see further consolidation to scale up the ‘right’ companies, just as in the first six months of the year, and it would appear that equity investors are happy to support this. Slowly and very painfully Darwinism is shaping the REIT sector into what it should be, more than 12 years after its creation: namely, low-leveraged balance sheets, long-term income streams (preferably RPI-linked from strong covenants), and with that rising income stream then being passed through to investors as a sustainable, growing dividend. That – and nothing more – is the object of the exercise, after all. Sounds simple doesn’t it? But if you’ve got it, you’ve got a premium rating and opportunities; stray far from it, and the discount to NAV is an embarrassment.