Another instalment in a series of articles detailing how to design a secure, income-producing portfolio.

There are around 72 million baby boomers in the U.S. and they’re an affluent group. They account for less than a quarter of the U.S. population but half of net household wealth, as of 2015, according to Deloitte. Much of that wealth is held in IRAs, 401(k)s, or other investment vehicles; in other words, most of their wealth is in stocks. As they retire, currently at a rate of 10,000 a day, a lot of these boomers are planning to sell stocks to generate cash to live on. That means that this enormous swathe of the population has purchased securities on the assumption that, at the very moment they will all need liquidity, markets will be sufficiently bullish to support them all selling at more or less the same time. That’s market timing on a grand scale. A lot of people are making a big bet, with their retirement security hanging in the balance.

There are already reasons to think that this bet won’t go as well for them as they’re hoping. We know that the decades during which boomers poured the greatest volume of savings into liquid securities also coincided with a period of high stock valuations. This makes intuitive sense as a simple matter of supply and demand. The baby boomers, who are the largest generation in U.S. history, demanded securities in great volume, to serve as their savings vehicle; their demand is essentially the aggregate of millions of those individual financial planning meetings. Their collective hunger for stocks would naturally push prices up, and price data support this idea.

Will U.S. stock markets experience a steep decline and a 20-year bear market when the bulk of the boomers have cashed out? No one knows. Market timing is a bad idea because we don’t know how markets are going to behave in the future, and if we project that they’re going to be bearish we can be no more certain than if we’re projecting bullish. At a minimum, though, we should not merely presume that markets will accommodate our retirement.

Plenty of people argue that the boomers’ retirement will not inflict great pain on markets. The most common defence, and one often made by large financial institutions, is that markets are highly efficient at pricing in widely known events. According to this view, everyone knows the boomers are going to retire and sell a lot of their stocks and thus it’s already priced into today’s valuations.

This argument is, of course, rooted in efficient markets hypothesis (EMH), which we unpacked in a previous article. We now know that EMH is an unproven theorem, not a fact, and moreover it’s a theorem based on a rear-view[1]mirror assessment of markets. But the retirement of the boomers is an unprecedented event in U.S. financial history. The EMH cannot predict the impact of a boomer exodus, as it has not seen anything similar. It’s possible that the very fact that so many millions have crowded into the same strategy at the same time is evidence that retirees are not accounting for the potential consequences of a bulk selloff. Everyone needs retirement savings (stocks) and everyone needs cash in retirement (sell stocks, at more or less the same time). For each individual, the strategy makes sense. It’s in the aggregate that it’s dangerous.

Perhaps the most plausible argument against a post-boomer market downdraft is that the Fed will step in to forestall the worst pain. You could argue that this is already happening. The very first boomers turned 65 in 2011, and since many retirees spend cash reserves before liquidating securities, it’s plausible that a large selloff is only just now getting underway.

“The idea that the Federal Reserve will always find a way to step in and inject liquidity stimulus to support stock markets is increasingly common.”

But a quick glance back at history shows this is a new development. Historically, central bank liquidity stimulus was viewed as a temporary action, to be used in crisis conditions. Indeed, the Fed was always seen as “the lender of last resort.” This changed with the Great Recession. Since then, there has been an unprecedented volume of monetary stimulus that has continued far longer than any prior lender-of-last-resort activity. That is, while the lender of last resort was originally intended to be just that – a last-resort intervention – we have made monetary stimulus an almost permanent fixture.

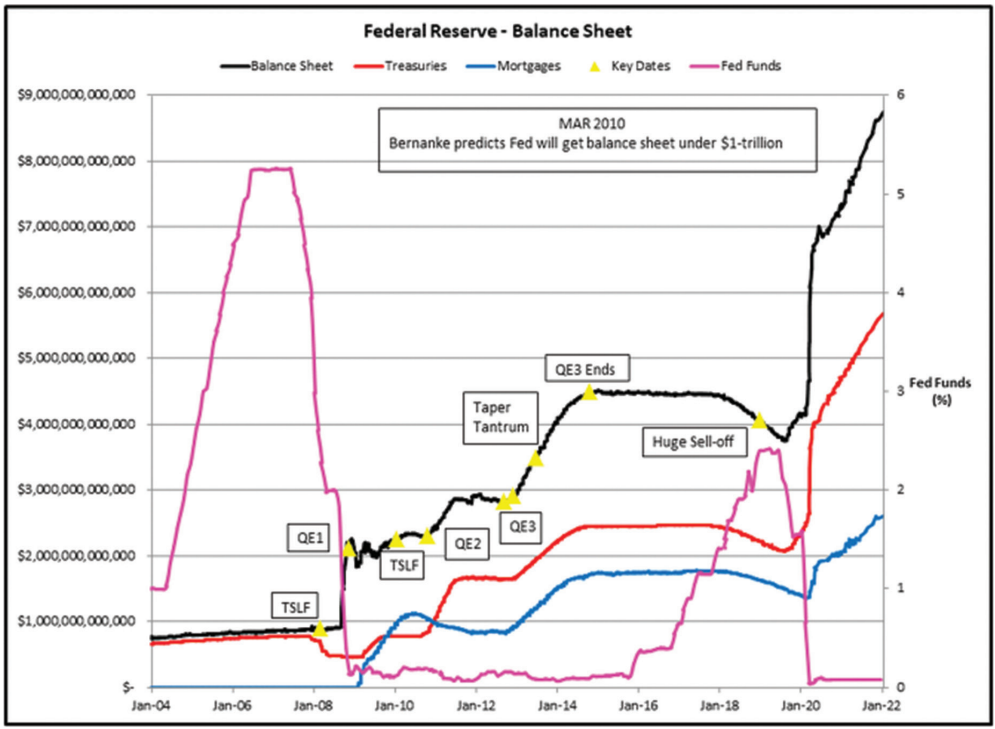

We have, in a sense, become dependent on the Federal Reserve, which continually acts as if our economy and financial markets are on life support and constantly require fresh oxygen and a blood transfusion. This is a dangerous state of affairs. Given that the Fed is already using its tools on a day-to-day basis, it has limited options in the event of a real problem. The Fed balance sheet soared above the $1 Trillion mark for the first time in the wake of the 2007-2008 Financial Crisis and continued to rise into 2014 where it stabilized at around $4.5 Trillion. The Treasury Balance Sheet had begun to contract below $4 Trillion when COVID hit, and then reversed and exploded higher to nearly $9 Trillion where it sits today. The balance sheet is comprised of approximately 2/3 U.S. Treasuries and 1/3 Mortgage debt.

But “free money” is never free. The Fed kept interest rates, as measured by the 10-year Treasury, below 1% for most of 2020. During 2021 the 10-year rate rose above 1% and last year exploded above 4%. Today’s rate is approximately 3.9%. This was an unprecedented increase in rates which produced the worst performance for U.S. bonds over their 250-year history. In 2022 10-year bonds lost over 10% while longer-dated 30-year Treasury bonds lost almost 40% in value.

Real estate markets are still adjusting to the higher cost of debt and may continue price discovery during the balance of 2023. May markets have not yet seen a market clearing price that fully incorporates slower fundamentals and higher rates. Yet the bigger issue is that the Fed has kept interest rates low ever since the financial crisis, which gives them little room to move in the event of a new catastrophe. If the Fed can’t move interest rates back down, it’s then left with its other tool: expanding the money supply. But that creates inflation. It’s like we’re in a low-riding vehicle and kicking out our shock absorbers.

The ultra-low interest rates and interest rate volatility also have side effects of their own when we’re facing near-zero or even negative rates. When the cost and availability of debt capital moves fast, people don’t know how to respond. Where should they go, where do they put their money? As a result, people are currently moving huge tracts of cash around the world, putting money back into fixed-income instruments that they had previously pulled out of. These big movements affect the markets, of course, creating uncertainty and volatility. For this reason, we are now seeing the type of volatility previously associated with market lows at market highs. And as I’ve said, and will continue to emphasise, volatility is expensive.

The Fed’s activities may already be counteracting the effects of the boomer retirement, but not without costs. Remember, every person of the same age expects that their retirement accounts will accommodate their needs, all at the same time. And even as rising volatility exacts a toll in the present, the greater danger is that we encounter a genuine crisis and discover that our central bank is out of options. We’re removing supports from our system all the time – and, simultaneously, vast numbers of retirement-savers are engaging in market timing, gambling their living standards on the myth that markets always will accommodate them.