While some argue that covid-19 measures are the start of a permanent new universal basic income (UBI) to mitigate the risk that societies are entirely torn apart, others see UBI as a draw for (younger) people to migrate to cities. Another line of thought sees UBI as a potential impediment for workers looking for self-fulfilment in urban jobs.

Let’s look at some of the socioeconomic data in Europe in order to better understand the various lines of thought:

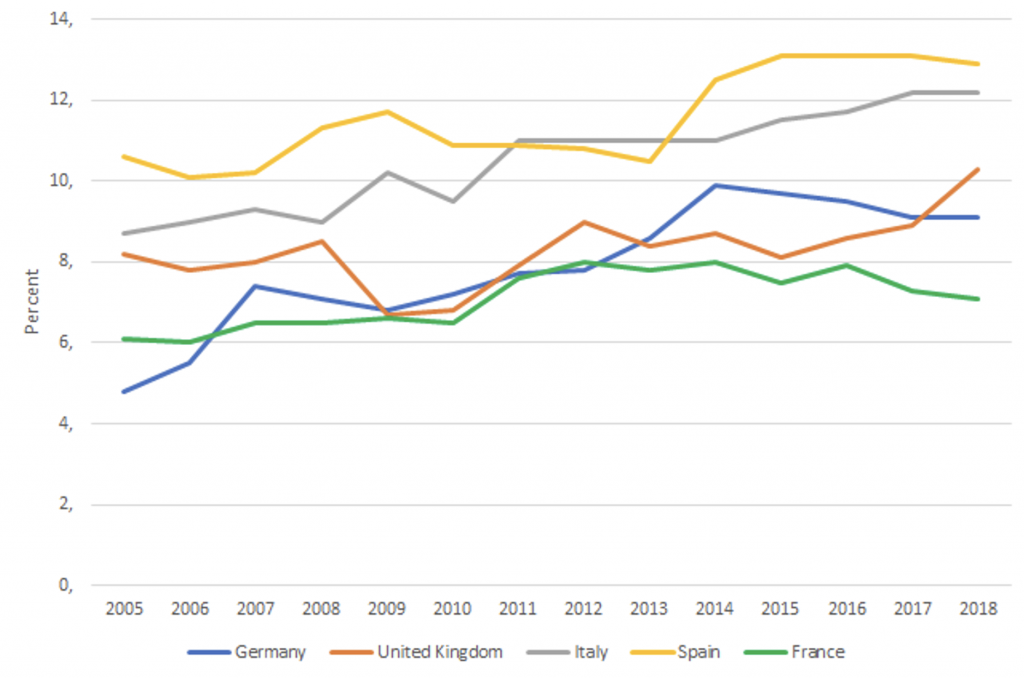

In-work at-risk-of-poverty ratio

(60% of anational median income, all employed adults aged over 18)

Pretty much all large European economies saw a significant rise of the ‘working poor’ since 2005, most notably Germany (4.8-9.1%). The ‘working poor’ group is defined by having 60% or less of their respective national median income.

When drilling down on those numbers (thanks, Eurostat) two main disparities become obvious: age and education.

Let’s see how this impacts the ‘working poor’ ratio.

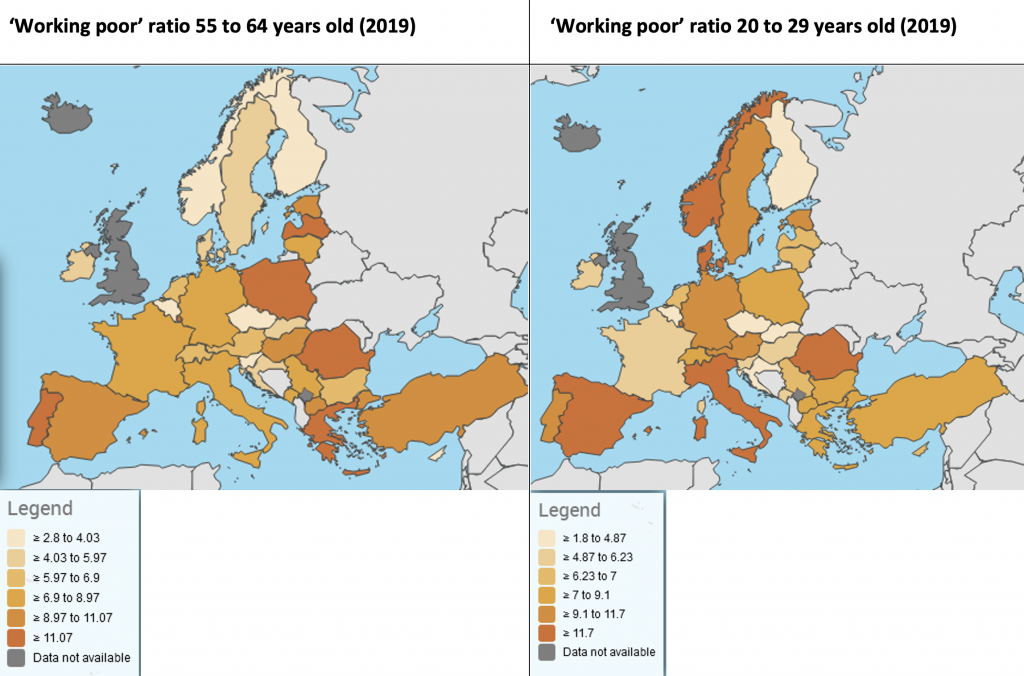

The effect of age on the ‘working poor’ ratio

There is a significantly higher risk for entry-level employees in their twenties to belong to the ‘working poor’ portion of the labour market, especially in southern Europe, but also in economic powerhouses such as Germany and countries with an abundance of natural wealth like Norway.

Now, let’s take a look at education as an indicator for the risk of belonging to the ‘working poor’ group.

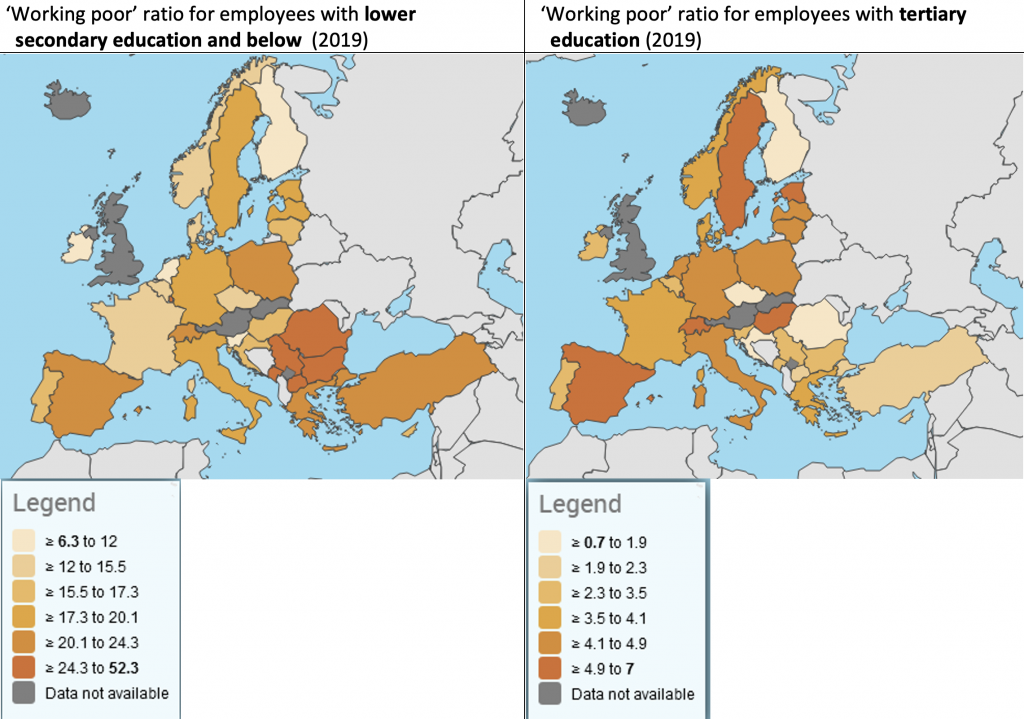

The effect of education on the ‘working poor’ ratio

Well, while the story told by these heat maps above isn’t terribly surprising, it is still stunning to see that the maximum risk of belonging to the ‘working poor’ group is up to 7x higher for folks with a lower secondary education or below, compared with those who have had a tertiary education.

In 2019 the entire EU-28 area (pre-Brexit) had a total of 24.1 million people in its working population with a lower secondary education or below (maximum nine years of schooling). Some 4.2 million of these work in retail, hospitality and food services.

Taking all this data in and considering the impacts of almost a year of lockdowns, a particularly vulnerable group emerges.

But there are other (pre-covid-19) indicators too which make the UBI discussion timely and necessary.

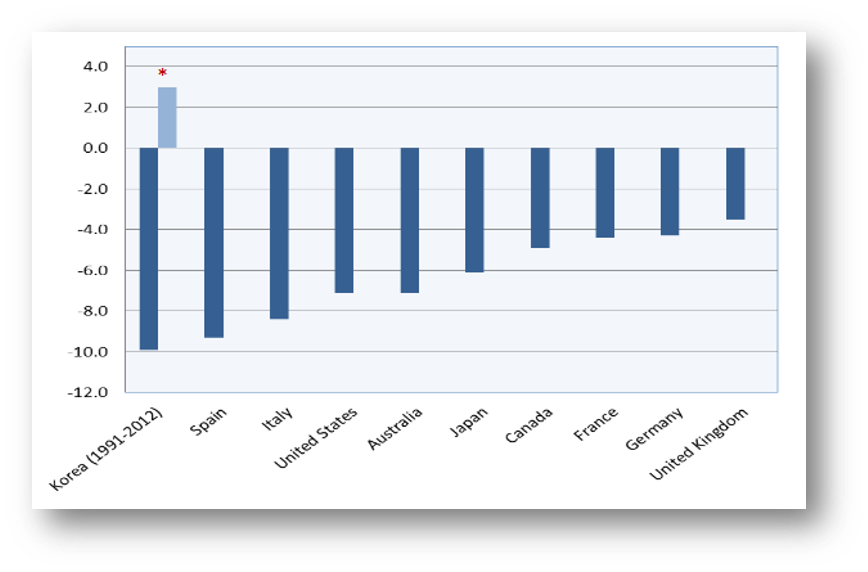

Between 1970 and 2014 the labour share across major G20 countries saw a constant downward trajectory. Given the rapid replacement of manual labour with digitised and automated processes (think department store versus Amazon, traditional warehousing and conveyer belts versus fully automated/digitised/robotised warehouse and manufacturing facilities) in recent years, this trend has been gaining significant momentum. Covid is just the shot in the arm.

Changes in labour shares in G20 countries (plus Spain) 1970-2014

Now, OECD research shows a direct relationship between a decreasing labour share and increased income inequality. This trend is a particularly troublesome development in continental European countries with a social fabric historically geared towards less disparities.

Evolution in labour income share versus Gini index (2000-15)

So, where does this leave us?

Well, UBI is an interesting concept, which arguably has been deployed by some European countries as part of their social safety net for quite some time using different headings. As the holy grail of income and wealth distribution, UBI is rather similar to programmes like the top-up income paid in Germany, received by 9.2% of the population. This includes 1.3 million ‘working poor’ in Germany alone.

Will we see more (camouflaged) UBI in the wake of the covid-19 fallout?

Absolutely. The inability to earn due to lockdown restrictions will make it the single source of income for many. Structural labour market changes will add job losses. It probably won’t be called UBI, but if you look closer it will have all the same features.

Would UBI be a facilitator for people to migrate to cities?

It depends. For those looking for enhanced education, skills and earning power, it would. For others whose earning capacity against a city’s costs level remains low, UBI would be better spent outside urban areas… from a purely homo economicus’ point of view, that is.

Would UBI be a potential impediment for workers looking for self-fulfilment in urban jobs?

Well, I don’t think so, unless the self-fulfilment is mainly manifested by slogging for the next bonus cheque, which is unlikely to be replaced by a rather modest UBI. Moreover, UBI would add choice for workers to seek work fulfilment either through pursuing an ancillary interest or to bridge the potential income gap while telecommuting from a lovely country house.