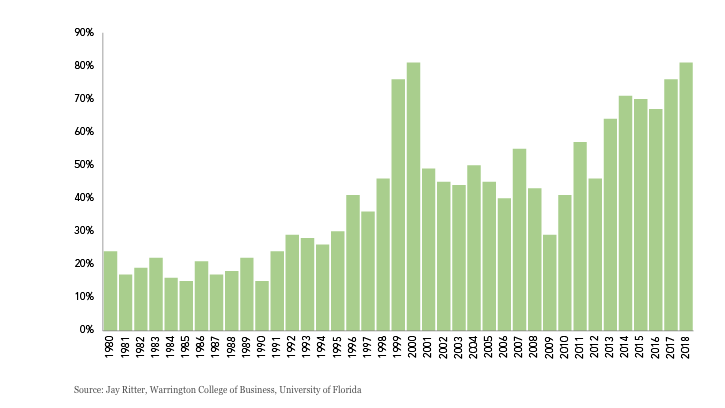

The percentage of unprofitable companies listing on public markets has never been higher.

Percentage of US IPOs which are loss-making

This is the year of the tech unicorn IPO. So far we have had Uber, Lyft, Beyond Meat and Pinterest; later in the year we expect to see AirBnB, WeWork, Slack and RobinHood. In the last two years, there was also Spotify, Deliveroo, Hello Fresh and Snapchat. The slate looks like the app menu on a millennial’s iPhone.

So what do these companies have in common? Well, aside from being predominantly conceived in Silicon Valley, their customers being young professionals and being backed by the new Masters of the Universe in venture capital, none of these businesses make a profit.

Bizarrely, this seems to be a badge of honour. One eminent investor said ‘profits are what you make when you run out of good ideas’ and in one fell swoop turned centuries of accepted mercantilist wisdom on its head. Investors are being asked to imagine what these companies might one day become – but pay up now. The problem is that in making consistent losses, someone needs to keep writing a new cheque to keep the business going.

‘We may never achieve profitability’ confessed Uber’s own IPO prospectus. At a peak valuation of $1o0bn, this should make shareholders a little nervous. The products are ubiquitous: some have reached the status of verbs. The business model is a land grab – sell at a loss to gain market share then squeeze and disrupt incumbents. The end goal is market domination, raise prices and earn monopoly profits at some point in the distant future. This is the Amazon playbook and it is a long game – 24 years in and 2018 was the first year the core retail business made a meaningful profit.

Unicorns embody today’s new era thinking. Revenue growth and TAM (total addressable market) are the key metrics. Beyond Meat aims to grow sales by 22x over the next decade, maybe it will, but where are the barriers to entry in veggie burgers? Uber’s estimated TAM is a somewhat optimistic 15% of world GDP.

Zero interest rates make this possible. The opportunity cost of capital is very low and depressed discount rates mean profits far into the future are still worth something today. In a low growth world, growth of any kind attracts capital.

Consumers love these products because they are hugely subsidised. Customers are incentivised to switch from incumbents. Every dollar these companies lose is a dollar back in the pocket of consumers. If investors ever demand a profit margin, prices would have to rise.

John Kenneth Galbraith described ‘the