I think you would be hard pressed to find anyone who thought house prices were cheap.

For example, a 30-year-old first-time buyer will need a 5% deposit at the very least.

The average UK house price (according to Nationwide) reached £273,000 in 2022, so even a measly 5% deposit will set them back almost £14,000, and few 30-year-olds have that much cash sitting around.

No wonder home ownership among 25-34-year-olds has almost halved over the last 30 years, and that the proportion of joint first-time buyers has increased to 63%, outnumbering individual first-time buyers who used to make up the majority.

This is clear evidence that house prices are simply unaffordable for most people under 30 unless they pair up with someone and buy as a couple.

The other option is to borrow from The Bank of Mum and Dad (BOMAD), if you’re lucky enough to have one. BOMAD lends about £5 billion per year, funding about £80 billion of property purchases that otherwise wouldn’t happen.

The growth of BOMAD lending is a key reason why the average deposit (according to the Halifax First-Time Buyer Review) is now an astonishing £62,000. That’s more than the average house cost in 1997.

And even if our intrepid first-time buyer does manage to scrape together a 5% deposit, they’ll need a 95% mortgage. If they want to buy an average house with its average price of £273,000, they’ll need a mortgage of about £260,000.

If our first-time buyer earns the average UK wage of £32,000, they’ll need to borrow eight-times their income. That’s a problem because most banks only lend up to five-times income. If you need more than that you’ll need a salary far above average or a much bigger deposit (most likely via BOMAD).

If our first-time buyer is half of a couple, there is a chance they could buy using Nationwide’s Helping Hand scheme. If they earn a combined £55,000 or more, Nationwide might lend them 5.5-times their combined income, or £302,500.

So that’s one specialised product from one lender in the market who might be able to lend the average 30-year-old couple enough to buy an average house without a huge deposit from BOMAD.

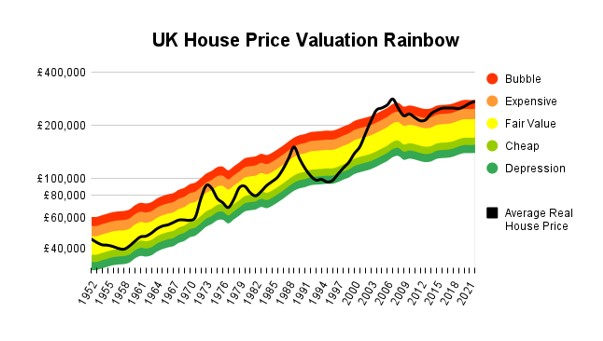

To me, this is another clear sign that houses are massively overvalued. In fact, I don’t just think house prices are overvalued, I think they’re in yet another bubble.

The bubble argument is based on the house price to earnings (PE) ratio, because there is obviously a strong connection between how much people earn and how much they can pay for a house.

The amount first-time buyers can pay comes from a combination of their mortgage (four or five-times their income) plus their deposit (historically less than one-times income), so we should expect the average house to cost something like five or six times the average wage, and that’s exactly what we’ve had in the UK for most of the last 70 years.

Occasionally, something happens to push prices above their normal range, and the housing PE ratio has varied between 3.9 in 1995 and 8.6 in 2022, but these periods rarely last more than a few years.

For example, the 1980s property boom peaked in 1989, when the average house cost 6.9-times the average wage. The boom then turned into a bust, with house prices falling 21% in nominal terms and 44% relative to wages.

The 1980s boom was followed by the 2000s mortgage bubble, where banks gave 125% mortgages to anyone with a pulse. That bubble peaked in 2007, with the average UK house costing 8.5-times the average wage. Once again, the bubble burst and over the five years from 2007 to 2012, the average house price fell 12% or 25% when adjusted for inflation.

That bubble was followed by the current Help to Buy bubble, which the government began inflating when it launched its idiotic Help to Buy scheme in 2013.

Help to Buy enabled more than £100 billion of home purchases that otherwise wouldn’t have happened, and pumping that much money into the housing market, with no meaningful increase in supply, inevitably led to massive price increases and another unsustainable bubble.

At the peak of the Help to Buy bubble in 2022, the average house cost an incredible £273,000, or 8.6-times the average wage. That leaves the housing PE ratio at its highest level for more than 70 years.

History tells us that all bubbles eventually burst, so the housing market is now extremely vulnerable to some combination of (a) higher interest rates, (b) a deep or prolonged recession and (c) negative sentiment towards buying a house.

Some of those risks have begun to crystalise and there is a real chance that the average house price could revert to a historically average 6-times earnings.

If that happens in 2023, house prices could fall as much as 32%, from £273,000 to £186,000.

However, I don’t think that’s likely. Instead, a far more likely outcome is that house prices fall to historically average valuations over the next five or ten years.

If inflation somehow remains at the Bank of England’s 2% target (which seems like wishful thinking) and if earnings grow 1% faster than inflation, a reversion to historical housing valuations would give us the following scenarios:

(1) If the housing PE reverts to a historically typical 5.8 by 2028, the average house price would fall by 21% to £216,000. This is similar to what happened when the 2000s mortgage bubble popped.

(2) If housing PE reverts to a historically typical 5.8 by 2032, the average house price would fall by 8% to £250,000. This seems like a more positive scenario, but it means that house prices would slowly decline, year after year, for an entire decade.

A prolonged decline could put millions of young people off buying a home, and that is exactly what pushed prices so low in the 1990s crash. So, here’s my third and final scenario:

(3) If the housing market is in a 1990s-style depression in 2032 (housing PE of 4.0), the average house price would fall by 37% to £172,000.

Some people will say that the government would step in to save the day. But if it does, it will only make the problem worse in the long run.

Personally, I would rather see house prices decline to fair value over the next five years, through a combination of price declines and above-inflation wage growth. But whether that happens or not is another matter.