My wife and I went pillow shopping on Oxford Street over the weekend – doing our bit for brick-and-mortar retail (you’re welcome, kind reader). On the way home, we were switching from London’s Elizabeth Line to the Overground when, to our bemusement, a fellow commuter decided to await their friend at the foot of the escalator. As you’d imagine, what followed is best described as a mechanically fed human pileup… perhaps we really should fear the rise of the machines.

This situation reminded me of a recent commitment I made to an industry colleague to share a simple mathematical equation known as Little’s Law which could estimate the impact of the UK’s much derided homebuying process on the availability of homes in the private rented sector (PRS). If you don’t get the relevance of the escalator straight away, be patient. It’ll come.

What is Little’s Law?

According to the Corporate Finance Institute, Little’s Law “is a theorem that determines the average number of items in a stationary queuing system, based on the average waiting time of an item within a system and the average number of items arriving at the system per unit of time.” It was introduced to me a number of times throughout my tertiary education – most recently a few years back during a class on technology and operations management. The equation is used in manufacturing, retail, aviation, and many other fields. In this analysis, we’ll be using it in the home sale process to determine the impact of delays (average waiting time within a system) on the total availability (or supply) of homes in the PRS (average number of items in a stationary queueing system).

How long does it take to buy a home in the UK?

Estimates of how long it takes to buy a home in the UK vary widely. A general consensus seems to exist around three-to-six months which relegates a needlessly excessive percentage of the country’s housing stock to a state of occupier purgatory. According to Siran Seevaratnam from Osborne Clarke, some of the primary causes of this delay are marketing, loan applications, contract negotiations, surveys, and other factors. Added to the homebuying timeline are, of course, any challenges emerging from the negotiation, finance application or contract of sale processes. This is before any complexities emerging from the buyer and/or seller being part of a “chain”. Since completion of a sale can be achieved without titles formally being registered, Seevaratnam does not consider the HM Land Registry’s (HMLR) backlog as a significant factor in homebuying delays, however it could affect the perception of some buyers if the home is resold before registration of title is completed. On 26 May 2023, HMLR reported that although 33.9% of changes to existing registered titles are automated and processed within a day, 37.3% take longer than a month and that “in some instances these applications are taking around 6 months to complete.” Errors in an application, or a complex change or new entry can take upwards of a year.

Housing tenure in England

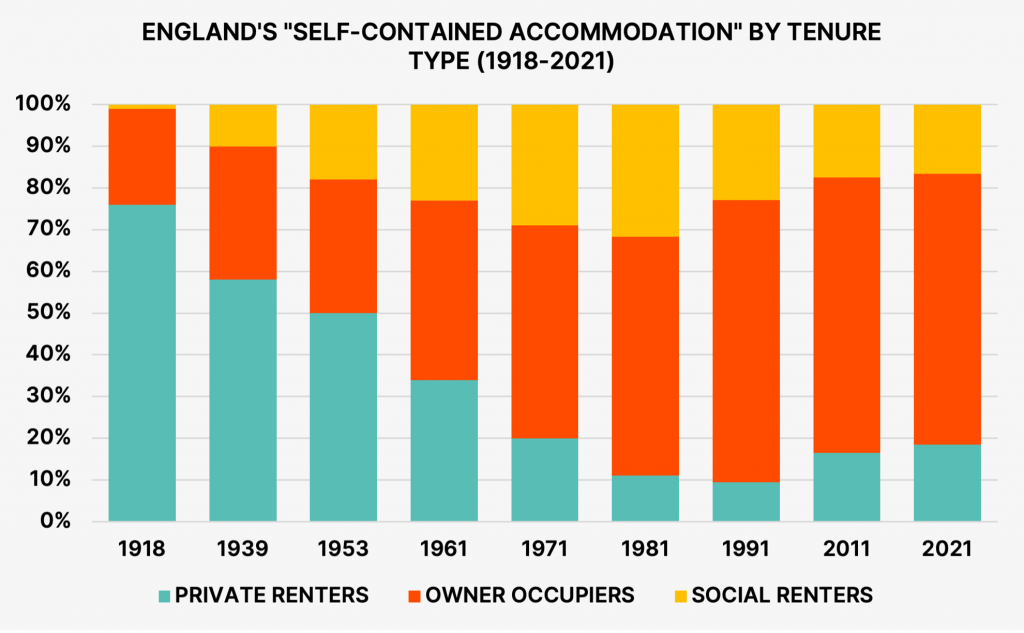

According to the 2021-22 English Housing Survey, there “were an estimated 24.2 million households in England living in self-contained accommodation.” Of these, 64% were owner-occupied (split further into owned outright and mortgagees). 19% of England’s self-contained accommodation was attributed to the PRS, and 17% to the social rented sector. This has changed over successive generations and continues to change (Figure 1). In the interest of simplicity, my analysis will treat these numbers as static.

Transaction volume, implied length of tenure, inventory

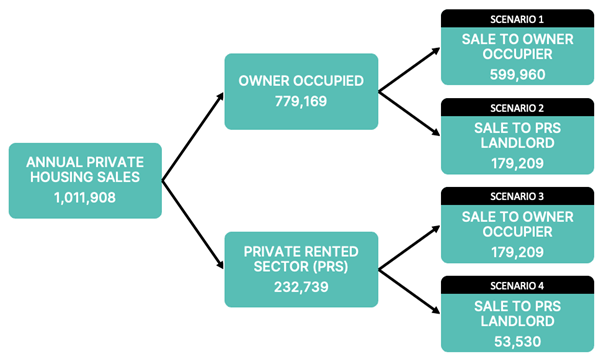

According to UK Government data on property transactions, the 10-year average annual count of private property transactions in England is 1.01 million (net of annual social housing sales) – resulting in roughly 5% of England’s owner-occupied and PRS housing stock being sold each year (and an average holding period of 20 years). By using current percentages of owner-occupied and PRS housing in the private housing pool, we will assume a probability of 17.71% for a private market home sale being from an owner-occupier to a PRS landlord (reflecting an average of 179,209 sales each year).

When private landlords face delays buying from owner-occupiers

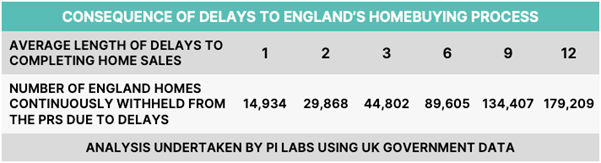

As shown in Figure 2, an estimated 179,209 average annual sales are made from an owner-occupier to a PRS landlord (Scenario 2). In this scenario, the total PRS stock in England increases by one. The delay in completing the sale can also be phrased as the delay in adding a home to the country’s PRS stock. By deploying Little’s Law, we can claim that longer delays result in a higher number of homes withheld continuously from the country’s PRS stock. If, for example, it takes an average of six months to sell a home, approximately 44,802 homes consequently aren’t available in the PRS. Each month increases the quantity of homes withheld from the PRS by 14,934 (see Table 1).

What happens when a PRS home is sold?

Figure 2 estimates that 232,739 PRS homes are sold annually. The seller is unlikely to be able to predict who will buy the home, but owner-occupiers-to-be represent the majority of the seller’s target market (Scenario 3). In this scenario, challenges emerge regarding tenant-in-situ, particularly in the first six months of a tenancy. Therefore, the seller is incentivised to appeal to this pool of buyers, which may include offering the home with vacant possession (evicting the tenant). It is also possible the tenant elects to vacate the property and find an alternative in order to avoid the uncertainty of the home being sold to an unknown buyer. In both cases, a lengthy sales period results in a lengthy vacancy (and demand for PRS housing, on the part of the former tenant, increasing by one). Every month these homes are vacant prior to completion represents 19,395 homes continuously withheld from the PRS. Further research could illuminate exactly how prevalent this is, and what level of rental vacancy it causes (for simplicity, Scenario 1 is ignored in this analysis).

When first-time buyers are delayed in exiting the private rented sector

Another type of transaction worthy of analysis is when first-time homebuyers are exiting the PRS to become owner-occupiers. Similar to the previous example, these scenarios involve a property transaction reducing demand for PRS housing by one. Delays to this process result in the first-time buyer remaining a tenant in the PRS, social housing or a family home longer than needed. If we assume just 200,000 of the UK’s estimated 356,000 first-time buyers in 2019 were exiting the PRS as a result of their purchase, every one month delay to their purchase resulted in an additional 16,667 homes continuously withheld from the PRS.

When property developers are delayed in supplying new PRS housing

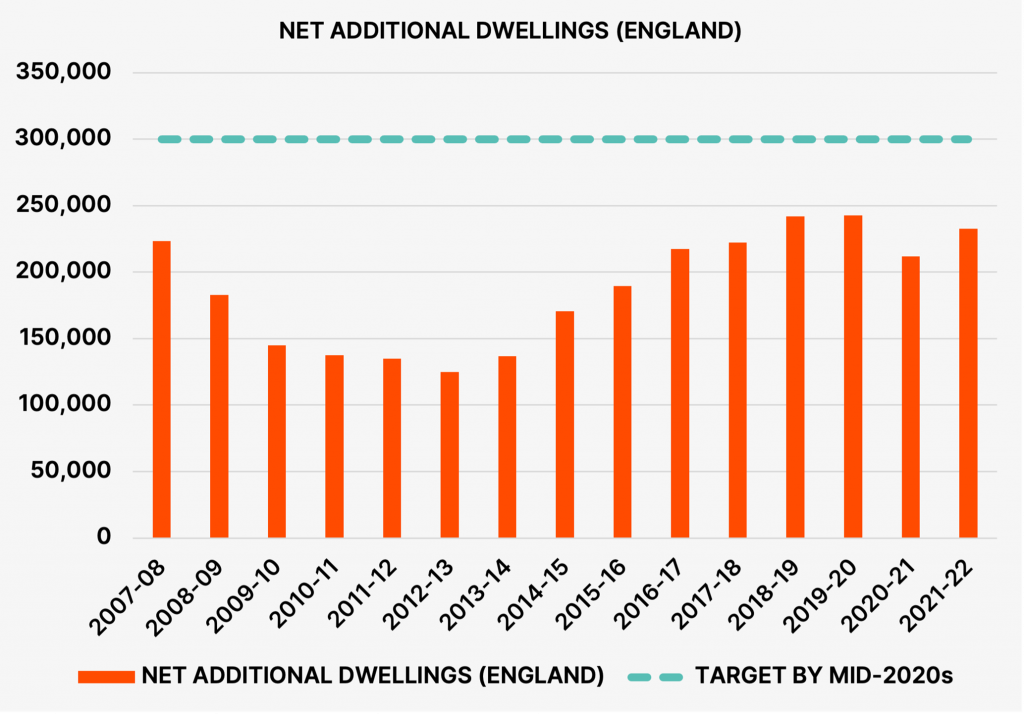

A recent Financial Times article cited “slow and inconsistent decision-making” of planning in the UK as a cause of “much-needed housebuilding and development”. The aptly dubbed “housing crisis” is being nominally addressed by the UK Government through a target to reach 300,000 annual net new homes in England by the mid-2020s, as well as a number of initiatives aimed at improving the quality of housing. In past years, the quantity of net new homes has fallen considerably short of this level (Figure 3). HMLR’s data offers a glimpse into the opportunity to close this gap. Given that 253,449 applications were made to HMLR for “first registration” and “transfer of part” titles in England and Wales over the 12 months to May 2023, Little’s Law tells us that each month of avoidable delay in the supply of new housing represents another 21,121 homes continuously withheld from England and Wales (or 4,013 withheld from the PRS when assuming existing ratios). Of course, there is also plenty to say about the phenomenon of “speculative vacancy” and “land banking” on the part of property developers.

Solutions

By combining the four areas analysed in this paper (owner-occupiers selling to PRS landlords, PRS homes being prematurely vacated for sale, first-time buyers exiting the PRS, and supply of new PRS housing), we end up with 54,589 homes continuously withheld from the PRS for each month of delay. In other words, shortening the homebuying process in these three areas by just one month automatically makes available up to an additional 54,589 private rented sector homes. So how can we make this happen? In 2015, Pi Labs invested in LandTech – visualisation and productivity software aimed at streamlining the property development process. Before platforms like this, developers faced the challenge of consulting troves of planning documentation sources and letterbox drops in order to achieve the same outcome. More recently, Laiout participated in our 2022 Growth Programme. Their aim is to reduce the inefficiencies of the design stage – in particular by offering AI-enabled floor plate suggestions which incorporate the relevant regulations of each jurisdiction. Both of these tools easily trim weeks or months off their respective legacy processes. Another area where technology and automation has been tested is in the conveyancing process – but this has been slowed by the fact that a 30% electronic adoption rate results in just a 10% probability of a transaction being completed electronically (due to the requirement for all parties in the transaction to have adopted the technology). Some technology adoption is therefore a quick win – improvements can impact individual transactions and scale over time. Others will require widespread adoption before tangible improvements eventuate. There’s a massive opportunity for technologies that can tangibly improve the homebuying process.