This article goes back to basics and outlines why a consistent record of dividend payments is the first thing I look for in a company, and why dividend cover is the first of many ratios in my investment spreadsheet.

Dividends make up the backbone of my investment strategy, so the first thing I look for in a company is a track record of consistent and sustainable dividends.

If you’re new to investing, here’s a quick definition:

Dividend per share (DPS): Dividends are cash payments made from a company to its shareholders. In theory, cash should be paid out to shareholders as a dividend when the company cannot invest that cash within the business at an attractive rate of return.

There are several reasons why dividends are central to my approach. The most important reasons are:

Dividends support efficient capital allocation

A company should only retain cash generated from operations if that cash can be used to produce an attractive return. The main uses of retained cash are:

- Maintaining the existing business

- Organically growing the business (e.g. buying stock or investing in factories, stores or equipment)

- Acquiring other companies

- Paying down debt

- Buying back shares

- When those options are exhausted, cash should be returned to shareholders as a dividend.

With companies that don’t pay a dividend there is, in my opinion, a greater risk that cash retained within the business will be used to expand the CEO’s empire (and pay packet) rather than maximise returns for shareholders.

Dividends create commitment and accountability

Companies with progressive dividend policies have made a promise to investors that they will maintain or grow the dividend each year.

This provides a public and very concrete goal for management to achieve. Of course this promise can be broken, but on average dividend-paying companies have historically performed better than non-dividend payers.

Dividends are a helpful yardstick

A progressive dividend gives investors a gauge for the long-term progress of a company. While earnings (and to a lesser extent revenues) bounce around from year to year, a progressive dividend can act as a more stable indicator of a company’s underlying growth rate.

Dividends provide investors with a regular income from their investments

Perhaps the most obvious benefit of dividends is that they’re a form of cash income. For investors who want an income from their investments, dividends are an excellent way to receive that income without having to sell any shares.

This removes any confusion around what is or isn’t a sustainable withdrawal rate, because withdrawing dividends should always be sustainable.

Dividends also provide an always-positive return which is independent of a company’s share price. This can help reduce the volatility of your portfolio and provide a positive return even if (heaven forbid) one of your holdings eventually goes bust.

Looking for a long record of continuous dividend payments

Benjamin Graham, the father of value investing, once said that “Each company should have a long record of continuous dividend payments.” The logic behind this rule is simple:

If investors want to buy companies that are likely to pay a consistent dividend in the future, the best place to find such companies is among those that have paid a consistent dividend in the past.

This leads to the first of many rules of thumb which I use to guide my investment decisions:

Only invest in a company if it paid a dividend in every one of the last ten years.

Most companies pay dividends multiple times per year, so if a company missed a single interim or final dividend then that may be okay, as long as some sort of dividend was paid every year. However, if no dividend was paid in one or more years then the company goes straight into my metaphorical waste paper bin.

Although I look for a consistent track record of dividend payments, it’s important to remember that dividends are paid at the discretion of the company’s board of directors. Unfortunately, this means you can never be 100% sure that a company won’t cut or suspend its dividend at some point in the future.

The coronavirus pandemic is a good example of this. During the global pandemic, even very defensive companies such as J Sainsbury (a supermarket) or AG Barr (maker of the IRN BRU fizzy drink) suspended their dividends. This doesn’t make them bad companies, it just means sometimes the economic outlook is so bad that suspending the dividend is the sensible thing, no matter how defensive the company.

Having said that, it is possible to invest in companies where the odds of suffering a dividend cut or suspension are relatively low, and the first step in that direction is to look for a track record of consistent dividends over at least the last ten years.

Getting your hands on ten years of financial data

There are various ways to get hold of a company’s financial results for the past ten years. The obvious place to look would be the company’s annual reports, but that approach is very time consuming and any per share data, such as dividends per share, will not have been adjusted for share splits or share consolidations.

Share splits and consolidations change the number of shares a company has and the price of each share, but they don’t affect the value of each shareholder’s holdings. However, they do affect per share figures such as dividends and earnings per share, which means per share figures from older annual and interim results have to be adjusted to take account of the change.

You could correct for splits and consolidations by hand, but my preferred approach is to get ten years of data from data providers such as:

- Morningstar

- SharePad (or ShareScope)

- Sharelockholmes

You can then supplement that as necessary with data from the annual results and reports, which you can find on:

- The company’s website

- annualreports.co.uk

- investegate.co.uk

- beta.companieshouse.gov.uk (including annual reports more than ten years old for when you’re doing a really deep dive on a company)

Now that we have the necessary data, let’s analyse the dividend record of a real company which has been in my portfolio at some point over the last few years.

Reviewing Ted Baker’s dividend

Ted Baker (TED) is a FTSE 250 fashion retailer listed in the defensive Personal Goods sector. It is known for its quirky British-themed style and has around 500 stores across the globe. It sells through three main channels:

- Retail (stores and online)

- Licences (product and geographical)

- Wholesale (e.g. through third party department stores)

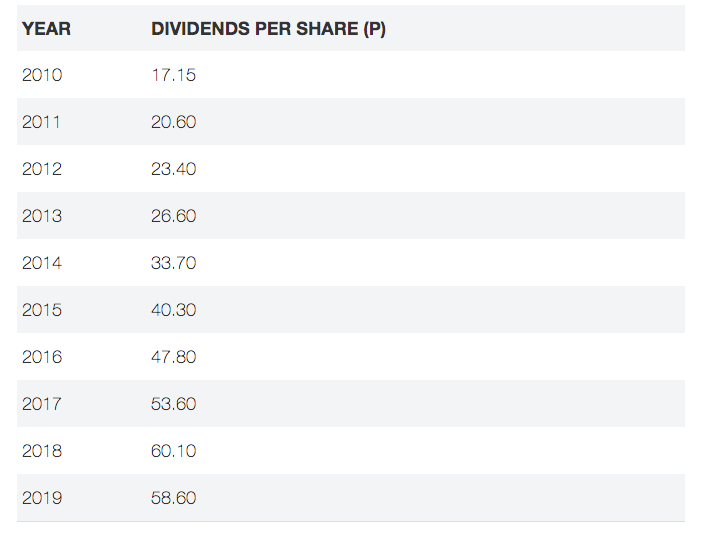

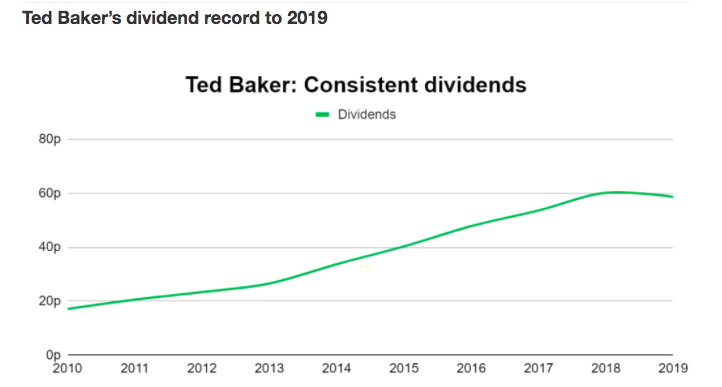

Ted had the following dividend record for the ten years to 2019:

Looking for dividend payments in every one of the last ten years is a pretty simple test. Either a company made a dividend payment in every year or it didn’t. In Ted Baker’s case it did, so at this stage of the analysis Ted would still be a viable investment candidate.

Looking for consistently covered dividends

Of course, dividends don’t appear out of thin air. A company must produce profits before it can pay dividends, and those profits will in turn depend on revenues.

To avoid any confusion, here are some more definitions:

Revenue – The total amount of money earned by a company during a given period (typically a year) before any expenses are deducted. You’ll find it at the top of a company’s income statement. It’s also known as sales or turnover.

Earnings – The amount left over after all expenses and taxes have been deducted from revenues. Also known as profit after tax or post-tax profit.

Earnings per share (EPS) – Earnings divided by the number of shares. It’s often quoted in pence and is the earnings part of the well-known price to earnings ratio (PE). Also known as reported or basic EPS.

Adjusted EPS – Some companies quote adjusted earnings figures. These remove one-off, non-recurring income and expense items such as income from the sale of a building or redundancy expenses following a plant closure. The idea is to provide a better picture of a company’s core or underlying performance by removing items that are unlikely to recur. Some data providers quote normalised earnings, which is a standardised version of adjusted earnings.

For many years I focused on adjusted EPS in an attempt to get a better view of a company’s underlying performance, without the distracting noise of one-off expenses. However, experience has taught me that adjusted EPS can sometimes paint an overly rosy picture of a company’s past.

This happens when a significant amount of expenses are repeatedly classified as one-offs by management, even when those expenses seem to recur year after year. Sometimes it can even look as if management are trying to make their results look better than they actually are.

To avoid this I now focus on basic or reported earnings per share, which always deducts all expenses. This gives me a better picture of how the overall company is performing, warts and all.

Calculating dividend cover

The calculation for dividend cover is relatively simple:

dividend cover = EPS / DPS

In other words, I want earnings to be greater than the dividend. I’m looking for consistently covered dividends, so my rule of thumb for dividend cover is:

Rule of thumb for dividend cover

Only invest in a company if dividend cover was greater than one in at least five of the last ten years.

Let’s see how this rule of thumb can be applied to another company I’ve owned in the last few years.

Consistent dividend cover at Burberry (BRBY)

Burberry is a FTSE 100 luxury fashion retailer. Like Ted Baker, it’s listed in the defensive Personal Goods sector. Also like Ted Baker, Burberry sells through three channels:

Retail (over 400 stores globally, plus department store concessions, discount outlets and e-commerce)

brand licensing (where other companies get to manufacture goods carrying the Burberry name)

Wholesale (e.g. department stores and other retailers)

Burberry paid a dividend in every one of the last ten years, so it passes my first rule of thumb.

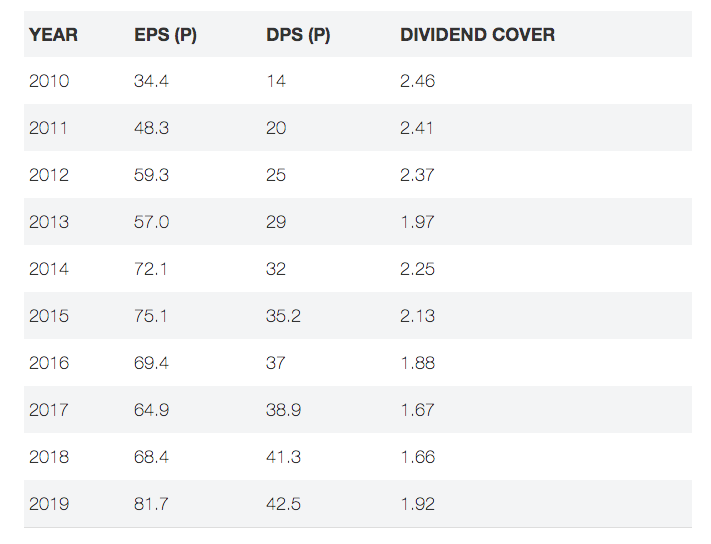

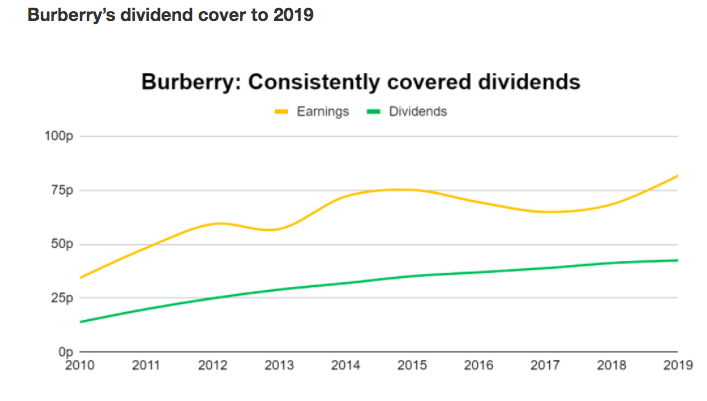

To check its dividend cover for consistency we’ll need the company’s earnings and dividends per share covering ten years, which you can see below.

As the table and chart above show, Burberry’s dividend was covered every single year, which means its dividend cover score is ten out of ten. Ten is obviously more than my minimum requirement of five, so Burberry easily meets my standard for dividend cover.

Obviously this is just the first step and there’s a lot more to do before a company can be deemed investable or not, so in the next article in this series I’ll go over how I measure a company’s growth, as growth is of course a key component of long-term returns.

For now though, here’s a quick reminder of my rules of thumb for dividends and dividend cover:

Rules of thumb for dividends and dividend cover

Only invest in a company if it paid a dividend in every one of the last ten years.

Only invest in a company if dividend cover was greater than one in at least five of the last ten years.

If you’d like to try out these rules of thumb, take a look at my investment spreadsheet.

Disclosure: At the time of writing I still held Ted Baker and Burberry. Ted Baker has suffered some high profile problems in recent years and I’ve already learned from and written about what went wrong at Ted Baker.