Who will keep the engine running when the next generation wants to become Youtubers?

Within the great variety of topics that younger generations worry about – climate change, equality, peace, etc. – demographics is not really seen as a pressing matter. The fact that the population is aging is widely known, but the consequences of this trend seem to be less often on people’s minds. This is probably the result of humans being short-term thinkers and an aging population is a slow process without obviously visible effects: there are no melting ice caps involved. At least, not right now. But who will keep our economy going when we are aging so fast? The old saying goes that “you can’t fight demographics”, but can we at least adapt to it?

Europe’s demographics

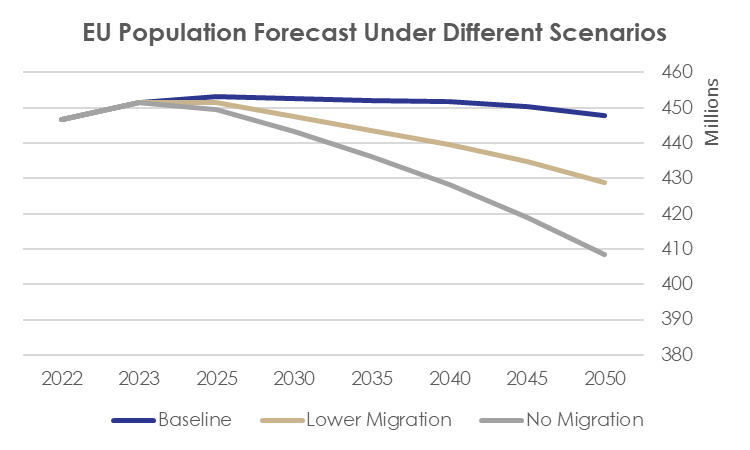

The baseline forecast from Eurostat suggests that the population in the EU will start shrinking from 2025 onwards. The pace of shrinking is however highly dependent on immigration. With conservative right-wing governments on the rise in large parts of Europe, it is not unlikely that immigration will be slower than initially expected. Eurostat’s “Lower Migration scenario” predicts a population loss of 23 million between 2023 and 2050. That’s more than twice the population of Sweden.

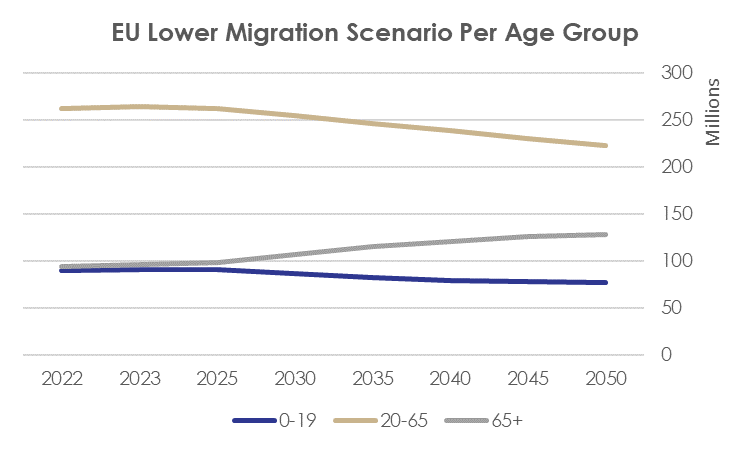

As Europe is aging as well, the population decline is coming forward in the age groups of 0-19 and 20-65. The number of elderly (65+) is set to increase by 32 million over the same period. This “grey pressure” ensures that more work must be done by a smaller number of workers, especially in sectors such as healthcare. This labour shortage deserves more attention.

The labour conundrum

Record-low unemployment and other economic forces have caused a shift in the labour market. Where workers used to follow job opportunities, now the job opportunities have increasingly started to follow workers. The demand for labour in most western European countries is high while supply is low. This is being reinforced by the aging population but also by changing geopolitics. Wars and trade regulations have caused disrupted supply chains over the past years, which is why more and more companies want to move their businesses back to Europe. This should grow the demand for labour even further. So how can we deal with this imbalance?

Well, there seem to be several (imperfect) options:

- Increase the retirement age: a highly unpopular measure but many countries already got started with this. As a 30-year-old, I don’t have any illusions. I will probably have to work longer than previous generations and it is likely that the retirement age will go up further over the next decades.

- Accept a slower economy and society: firms will move away to places with more workers available. Goods and services take longer to produce. Queues for childcare, health care and new housing will persist.

- Automation and AI: will this be our saviour? Maybe. The issue is, however, that AI will mostly replace office jobs in, for example, marketing, accounting and software. It seems unlikely that the people that lose their jobs in these sectors will switch to healthcare and construction. It’s problematic that AI is likely to replace higher-paid jobs because why would someone switch from a well-paid job to one with a lower salary? We may have to rethink the ways we compensate nurses, teachers and construction workers.

- Education and public image: the impact of social media on kids is quite scary to me, especially after reading several research articles on which profession kids want to have when they grow up. Apparently, at least half of them wants to become a Youtuber or influencer. I don’t think all of them will end up being one of course, but half of them sounds scary for a job that has no relevance in the wider economy. And you don’t need education to become a Youtuber: you can basically start right away. It might therefore become increasingly important to educate kids from a younger age on different kinds of jobs and attempt to change the public image of societally relevant jobs that lost popularity over time.

- Immigration: this is likely to be essential in filling the labour market gaps. Unfortunately, this often gets overlooked in the political debate. Selling this idea to the wider public might be difficult. Another hurdle is the need to make sure that immigrants can actually work, for example, by providing language courses or training. Nevertheless, strong anti-immigration policies might come back to bite us later on.

I think we will need a mix of all the options we have. How else will we have a house, a nurse and a pension by the time my generation can finally retire?

The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of Tristan Capital Partners.