The other day I met an intelligent and successful property developer (not always the same), who told me that back in 1997 he had sold a business and used the proceeds to move into buy to lets. He explained that he had built up a geographically diverse portfolio of properties in London, Kent and a fashionable university town in the north.

Sometime in the middle of 2007, after a sustained period of house price growth across the country, he sensed that it was time to think about taking a few cards off the table. So he sat down with his accountant and asked his views. The advice? Sell London and keep the rest.

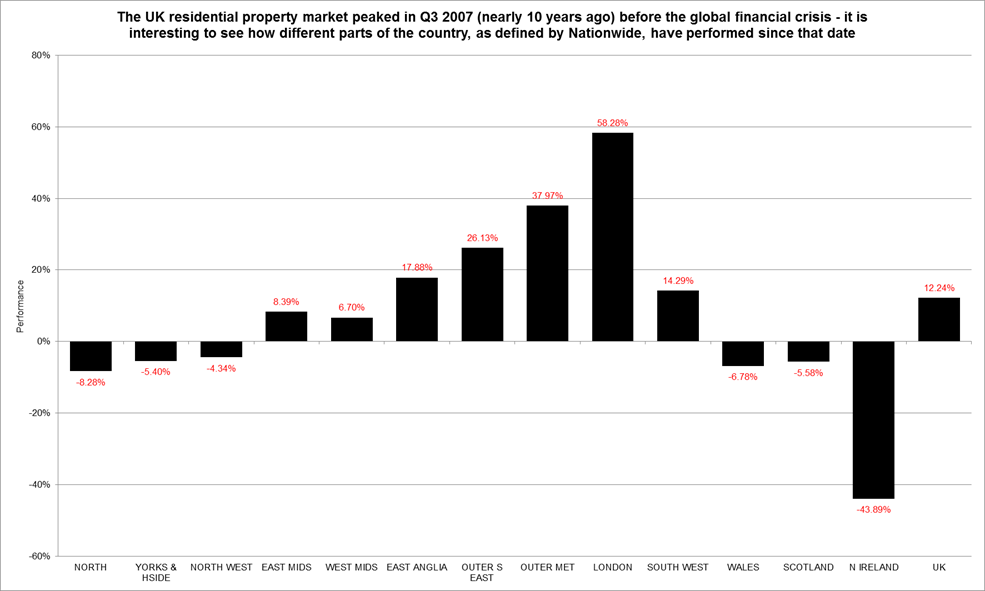

In light of that advice, readers may be interested to take a look at the chart below:

Chart data sourced from Nationwide and the Bank of England.

Chart data sourced from Nationwide and the Bank of England.

The bars measure the performance of each regional market since Q3 2007 (when, as it happens, almost all of the regional markets peaked). What is clear is that, nearly a decade later, six regions still remain underwater.

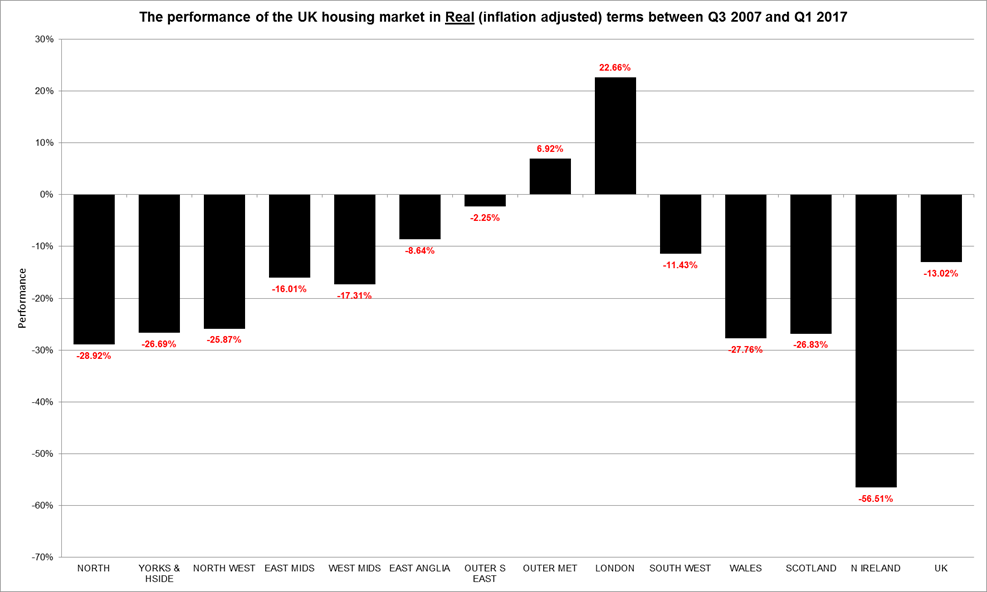

The next chart, however, is more relevant – particularly from an investor’s perspective.

Chart data sourced from Nationwide and the Bank of England.

Chart data sourced from Nationwide and the Bank of England.

This chart shows the real returns over the same period. You will note that that four of the seven regions that produced a positive nominal performance (the East Midlands, West Midlands, East Anglia and the South West), are actually down in real terms – which leaves us with London, and its immediate surrounding region, as being the only positive performers once inflation is accounted for.

The good news is that my new developer friend held on to his London portfolio and reduced his exposure to the regions. This story makes one take stock of the fact that, in spite of all the hype of late in the UK press about ‘house prices rising’, many regional investments have failed to protect investors’ capital when measured from the last peak.

This story also raises the investor’s dilemma of what you do when you suspect that markets are peaking. Do you sell your best performing stock (which between 1997 and 2007 was London) and hold the laggards, hoping that they will catch up? Or do you hold the best performers, trusting that the fundamentals will continue to drive performance?

The dilemma of what to sell and what to buy has always confronted investors over time, and across different asset classes. One similar example is brilliantly captured by Peter Lynch in the introduction to the first edition of his book One Up on Wall Street. On a golfing vacation in Ireland in October 1987, it became apparent that Wall Street was about to crash and there would be a significant requirement to raise cash from the anticipated outflows from his infamous Magellan fund. He took an immediate decision to reduce his weighting in cyclicals and increase his weighting in growth stocks – it was brave at the time, hurt in the short term, but proved very right in the long run.

Whenever I try to finesse markets, I’m always reminded of that wonderful phrase “top pickers and bottom pickers become cotton pickers”. If you stick to fundamentals you will win in the long run.