This article was originally published in December 2020.

The investor’s dilemma faces all of us: if we don’t invest, the purchasing power of our money will slowly decline; if we do invest, we are exposed to the risk of loss. It results in many sticking with cash.

A bank account feels safe. But the purchasing power of cash will erode in time: a dollar ain’t what it used to be. For many, a bank account is seen as the lesser of two evils. After all, investment offers no guaranteed return and no money-back guarantee. And there are always stories of investments that have gone wrong.

If someone is unable to invest in a way that preserves capital, is it any surprise they stick with a bank account? Losing money negates the purpose of investing. It is rational to avoid investing if we do not know how to preserve capital. But it is also rational to learn how to invest in a way that preserves capital.

We can resolve the investor’s dilemma if we can invest in a way that preserves capital over the long term. This offers an investment-style return without the risk of a large and permanent loss of capital. This article considers how to achieve this.

Short-term risk: volatility

For those with a short-term horizon, volatility is risk. A market slump is painful if you need to realise capital within the next couple of years. And market slumps happen from time to time. Investors with a short-term horizon are therefore advised to have a cash reserve.

All investors are at risk of market declines in the short term. But only investors with a short-term horizon need to realize a loss. In the short term, we cannot solve the investor’s dilemma. This is because we cannot both invest and avoid the risk of loss in the short term.

Long-term risk: capital preservation

Risk gets turned on its head when we are considering the long term. Investors with a long-term time horizon are not forced to sell at a loss during a market slump. Risk is no longer volatility because markets eventually recover. Risk is now the preservation of capital over the long term.

Investors with a long-term time horizon want to avoid the risk of a large and permanent loss of value. This is something that we cannot easily recover from.

We therefore need to invest in a way that will make the risk of a large and permanent loss of value negligible. This is how we seek to solve the investor’s dilemma over the long term.

Risk changes

It is hard to hold two contrary ideas on risk at the same time. In the short term, don’t lose money means we need to own bonds and/or cash savings accounts. In the long term, don’t lose money (in real terms) means we need to invest in volatile asset classes like the stock market.

To paraphrase Warren Buffett: Cash is less risky than stocks in the short term, but stocks are less risky than cash over the long term. (Provided you own good stocks.)

In practice, academics and investors tend to view risk only as volatility. In other words, what is the chance of losing money in the short term? Cash feels safe within this context. The hard part is conceptualising that a volatile stock market can be a safe place to invest over the long term.

Performance mitigates risk

Over the long term, the best protection is performance. Investing in real assets will generate a higher return than a bank account. Good performance will lower our exposure to the risk of loss. This is because it builds a performance buffer.

By way of example, a 25% housing slump can happen at any time. But if you bought your house 15 years ago and are up 300% on the purchase price, would a 25% decline matter?

Resolving the investor’s dilemma

Over the long term, the investment problem is to maximise our return while keeping the chance of a large and permanent loss of value at zero. Capital preservation is the constraint under which we invest. Techniques that help to preserve capital include the following:

1) Diversification through funds

Diversification has been described as the only free lunch in investing. It helps to reduce blow-up risk. In a portfolio of 25 stocks, a disaster for one company will only result in a 4% loss. Companies do blow up from time to time.

Investment funds deliver instant diversification. This takes a lot of the work, and transaction costs, out of the investing process. Funds allow us to diversify on a global basis, which is something that is hard to achieve when buying stocks directly.

Funds were invented to solve the investor’s dilemma by offering low-cost diversification. If selected well, they will be able to preserve capital over the long term. They are a simple tool that helps meet an investing prerequisite.

2) Start with passive funds

Passive funds should be the default starting point. A few active funds have gone very wrong in the past, with Neil Woodford’s funds a case in point. Active managers take concentrated positions with the aim of outperforming. But this only works out if the underlying companies are sound.

Passive funds are low-cost ‘plain vanilla’ investments. They require less monitoring than active funds. Companies that are performing badly will become a smaller part of an index. Passive funds are also lower cost and well-diversified.

In short, active funds have blow-up risk due to the nature of active fund management.

It is also the case that active fund management is a zero-sum game. This means that after fees, most active managers will underperform their benchmarks. An additional reason why low-cost passive funds should be our starting point.

3) Start with the world

People tend to invest in the stock market of their home country. We are most familiar with the companies listed in the country in which we live. There is also a perceived currency risk to invest overseas.

But unless your country has the world’s best stock market, it pays to invest on a global basis. A national stock market may also be higher risk because it is less diversified and exposed to the economy of one country.

Currency risk is short-term volatility. It doesn’t matter, if you have a long enough time horizon. If a global fund performs well, it will provide a buffer to absorb short-term currency volatility.

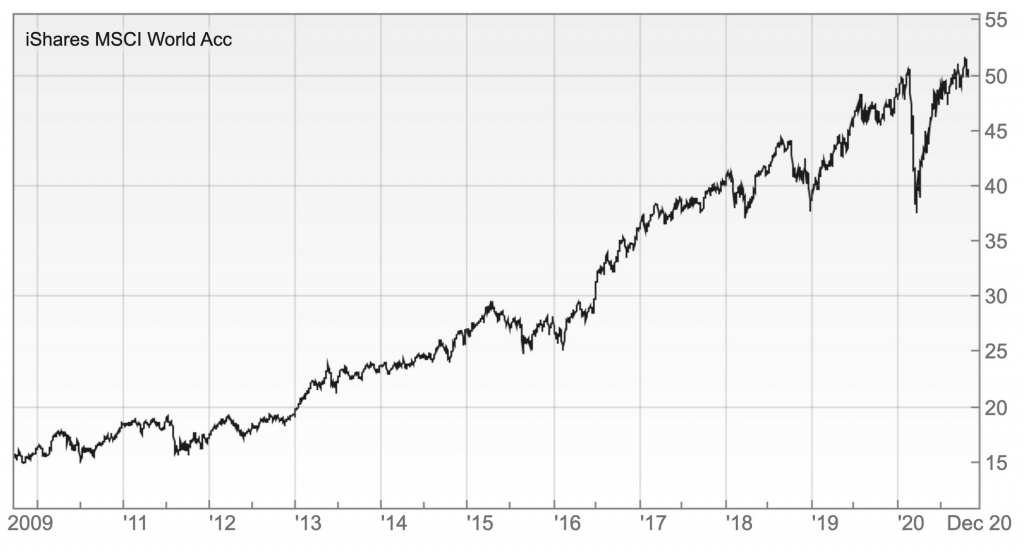

A prominent global passive fund is the iShares MSCI World ETF (SWDA) equity fund, with £20bn in assets. It acts as a useful starting point.

The iShares MSCI World ETF (£)

Seeking to add value over a World Tracker Fund

We can potentially add value to a global passive equity fund. The aim is to generate a higher return while keeping the chance of a large and permanent loss of value close to zero. This is achieved by owning funds with attractive companies and that avoid weak companies.

When it comes to fund investing, we do not have to pick individual stocks. We only have to 1) identify where winners are likely to be (e.g. sectors) or 2) identify investment managers that can pick winners.

We only have to be roughly right. Investing in individual stocks investing is not so forgiving. To quote the economist John Maynard Keynes: “It is better to be roughly right than precisely wrong.”

The following outlines our approach to fund selection at Fund Hunter.

Select passive first; active funds second

Passive funds remain the default starting point. There are a host of passive alternatives to the iShares MSCI World ETF. We can take positions on passive country, sector, subsector and factor funds. New passive funds come to the market all the time. While most are ill-conceived, there have been some gems.

The next stage is to consider active funds. Their performance needs to offset higher fees. The allure of active funds is that they can avoid lower-quality companies and potentially pick stock market winners. Active funds can be lower risk than an index if they own stocks that are less likely to blow up. In 2020, for example, we have seen significant setbacks in the banking, mining and leisure sectors.

Identify the best default fund

It is helpful to identify a default fund. This is what we would invest in for the long term if we could only invest in one fund. It serves as a benchmark to judge other funds. In other words, it acts as an opportunity cost fund. Are you willing to sell the default fumd to invest in an alternative?

We cannot add other funds just for the sake of it. They have to add value versus the default. The starting default fund is a passive world tracker like the iShares MSCI World ETF. But there are likely to be better default funds. The better the default fund, the higher the benchmark for other funds. It acts as a powerful decision-making tool.

When choosing funds, own good companies

Funds that owns good companies will inevitably do well over the long term. It is possible to overpay. But the biggest danger is owning companies that do not survive. Buying cheap companies is much like buying cheap used cars; they tend to go wrong.

We therefore look for funds that own good companies. We can do this either by analysing the companies or by analysing investment managers. When it comes to passive funds, we start with the stocks. When it comes to active funds, we can analyse the stocks and the process.

It is impossible to follow every company that a fund manager owns. The question is whether they have what it takes to pick winners and avoid losers. Do they have an edge over rivals?

What are good companies?

If the aim is to own good companies, we need to consider what they are. We want to own companies that have the wind at the back rather than a headwind. The hard part about investing is that it concerns the future. We cannot adopt rules based only on what has worked in the past.

Companies that have done well in the past may struggle in future; companies that are loss-making may be future stock market winners. Apple was dismissed by a number of active fund managers but is now the world’s largest company. Tobacco was one of the top-performing sectors but is now struggling with weak growth and regulatory change.

The end goal is to own companies that can both generate and grow free cash flow per share. This means strong customer relationships (franchise power) and a growth runway. Companies are valued in line with the scope to generate free cash flow. But if stock-picking were only about the historic financial numbers, it would be easy.

Summary

Our aim as investors is to generate the highest return possible while keeping the chance of a large and permanent loss of value at zero. Funds are a powerful tool to achieve this. They deliver instant diversification and we only need to be roughly right.

The investor’s dilemma has led to many sticking with low-interest bank accounts, but there is another way. For those with a long-term time horizon, the real risk is not investing.

A version of this article was originally published by Fund Hunter. This article is republished with permission.