I recently went on a private tour of one of the most eccentric private houses I have ever seen. Charles Jenks, who, very sadly died in 2019, was an architect and a polymath. He studied English Literature then Architecture at Harvard and his love of symbolism – which he used ostentatiously and without any regret in the few buildings (and, later, landscape creations) he designed – stemmed from his love of literature. Why, he reasoned, could one not use symbols in architecture when they were used with such success in literature?

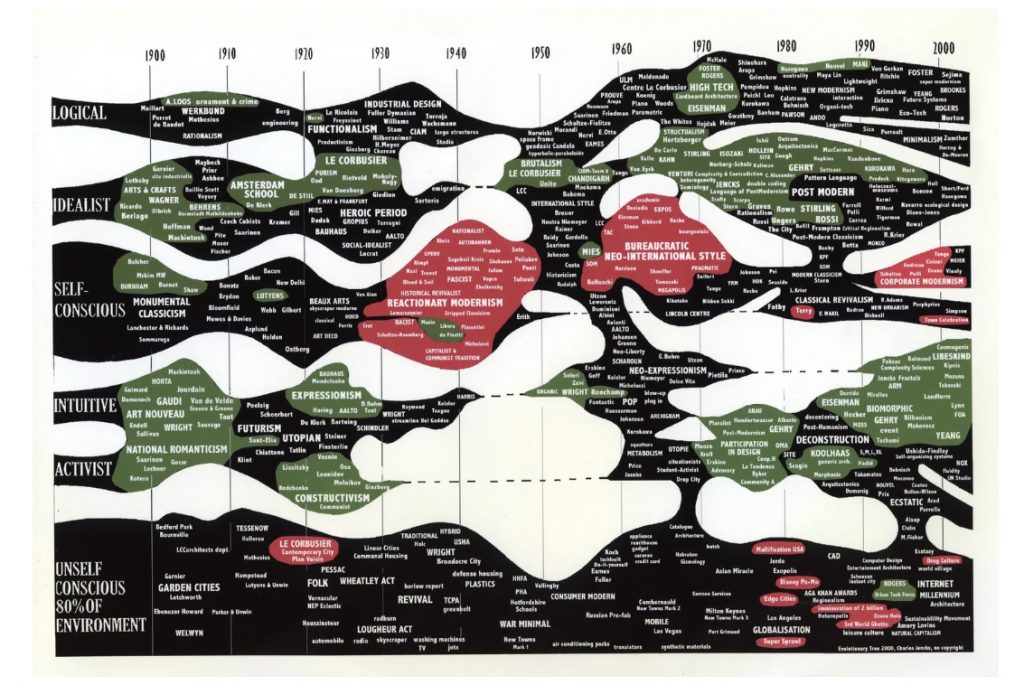

The Cosmic House in Notting Hill, London is a marvellous one-off shrine to one of the fathers of Post-Modernism. This surprising architectural, and now deeply unfashionable style resulted from the inevitable boredom with the rather serious and self-important modernism that preceded it and briefly gained ascendancy in the 1980s throughout the Western world. If I were to pigeonhole Charles Jenks, I would say he was one of the greatest “pigeon-holers” that ever existed. His great flowing diagrams of the history of architecture and its various movements mimicked Charles Darwin’s charts of evolution. Using these giant architectural flow charts, he coined, and later championed, the term “Post-Modernism” in architecture.

The Cosmic House sits in a rather plain late 19th century white stucco-ed residential terrace. However, upon entering, the house opens immediately to the fantastical world of Jenks’s mind. The main themes of his approach to architecture (sun/moon, heat/light) are engraved in the mirrored doors of the entrance hall – just in case you forget. Then turn right and you are placed in front of a fireplace (designed by Michael Graves) of magnificent and exaggerated proportions which, we are told, does not work. This is the whole point. The purpose of the fireplace is not to function as a fireplace but to function as a symbol of a fireplace. Charles Jenks once said, “A sign to me is a one-liner; but a symbol is very complex, and my house is a series of symbols.”

On the right can be glimpsed, through a glass screen, the centrally placed circular staircase. This spiritual centre to the house, is a spiral, a theme he was to develop later once Post-Modernism had passed its sell-by date and he had turned to landscape designs for a deeper understanding of the cosmos. Up to the dining room where the absurd kitchen design must have frustrated both his wife and staff. It was based on the idea of an Indian summer and mimicked the Hindustani temples of India, replete with spoons as relief motifs above the cupboards. Charles Jenks would say ironically “If you can’t stand the kitsch then get out of the kitchen.” He also said, “I am very serious about jokes,” and it is true that the house is extremely playful. It could even be described as witty, a trait often lazily attributed by critics to Post-Modernism.

Initially, Post-Modernism was successful in freeing up the world of architecture. However, Jenks later thought that it had become a pastiche, which he disliked, and turned his allegiance to cosmology. What I find remarkable is how he was able to bring together such a disparate group of remarkably talented architects to his cause. He was great friends with a very varied group of architects most of whom were in London and many of them teaching at the Architectural Association. There are some wonderful sketches, in the upstairs rooms, by Rem Koolhaas and Zaha Hadid, for example, whose approach to architecture could not be more different to his own. He was much loved even by those who did not agree with him and reveled in being the bow tied American eccentric teasing out the great and good of the London architectural world.

When I was studying at the Bartlett, in the early nineties, I remember a particularly earnest student, asking his tutor what she thought was the key to a successful architectural career. Her response, which the student found particularly deflating, was that he should first marry an heiress and go on from there. This is what Charles Jenks did when he married Maggie Keswick. Later, after Post-Modernism’s gleam had faded, he turned his attention to landscape projects in which he incorporated his eccentric views on creation and the cosmos, mostly on the Keswick estates in Dumfriesshires but also in Edinburgh. It is in these large landscape projects that many deem him to be at his most successful as a designer.

Designed by Terry Farrell, in conjunction with Charles Jenks

His greatest legacy, however, must be Maggie’s Centres, which were named after his wife, who died early from cancer. They provide care for those suffering from terminal illnesses. These small buildings were designed by a host of interesting and unusual architects such as Frank Gehry (Dundee), Richard Rogers (London), Richard Murphy (Edinburgh), Piers Gough (Nottingham), Zaha Hadid (Fife) and Ted Cullinan (Newcastle). I greatly respect his willingness to appreciate and commission works by such a diverse group of talents, especially as most of these names were completely opposed to the great concept of Post-Modernism that he so wholeheartedly embraced.

I only met Charles Jenks once, when I sat next to him at a private dinner at the Reform Club, where he related his musings on the world of architecture at the time. Not only was he a very charming man, but also, he was a versatile and deep thinker who had the grace to accept that there was room for more that one point of view. He was the opposite of Howard Roark, Anne Rand’s fictional architect hero and symbol of single mindedness in her novel The Fountainhead. Jenks had the guts to proclaim that symbolism was, indeed, not dead, but well and alive in his search for a fresh, new approach to architecture. When his wife died before her time, he was able to accommodate and celebrate the great variety and diversity of talent in the British architectural scene through the Maggie Center commissions which provide such uplifting spaces for those in need.

The Cosmic House has recently attained Grade I status and is now a museum. Those of you searching for a unique architectural experience should look no further.