Last week we looked at historical lessons derived from prior pandemics. Today we will expand into determining the likely economic fallout of covid-19, consider the capital market feedback and map the way forward.

How do we value the covid-19 impact?

My review of relevant academic literature finds a scenario outlined in a paper published by Fan/Jamison/Summers most reasonable. While prior studies focused on income losses only, their model employed a more comprehensive view. It expanded the directly measurable income losses by the costs of excess mortality, commonly referred to as a statistical life capturing the excess income an individual would demand for a corresponding increase in mortality risk.

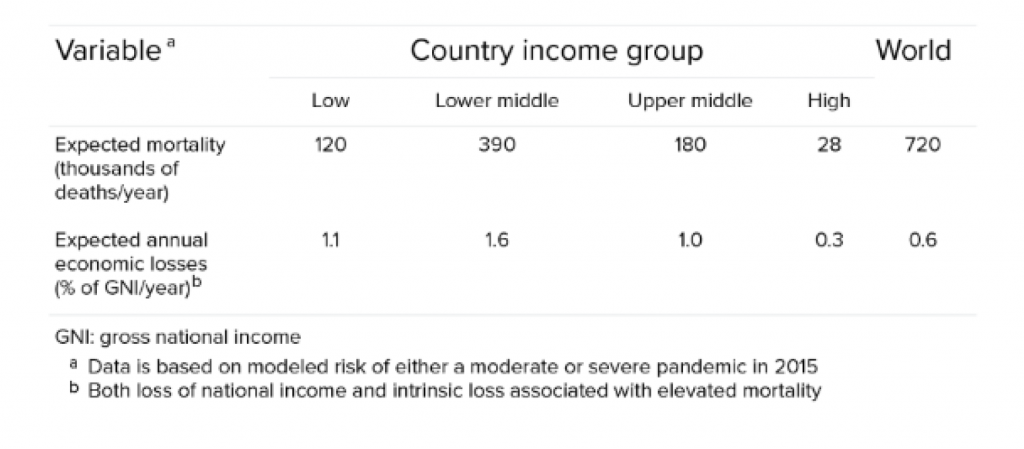

Using an ‘expected loss’ framework accounting for the risk of an uncertain event, expanded with information about the severity or value of that event, the paper arrived at the following impact matrix outlining mortality and economic losses of influenza pandemic risk, as in the case of covid-19:

Compared with the spring of 2020 the economic fallout from covid-19 is more visible today. Given the notable shortcomings in countries’ ability to handle and contain the outbreak but also the built-in economic mouse traps, like fragile supply chains, additional ‘resurrection’ costs will be incurred but are impossible to quantify from today’s perspective. Another big question to be answered will be the pandemic’s duration and severity. This is especially true in Europe and the United States, two regions with a combination of stunning unpreparedness, severe pandemic spikes and slow economic revival.

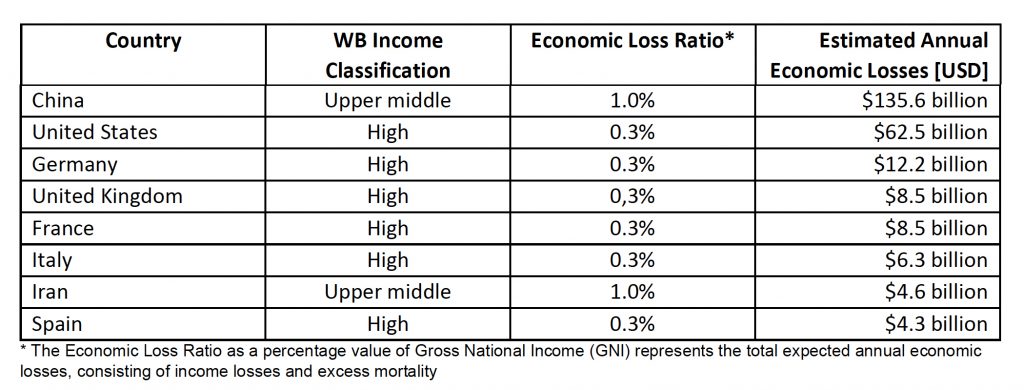

Based on the above, the following annual economic losses are to be expected:

Judging by officially available covid statistics and the seemingly quick economic recovery, the $135,6bn annual economic loss estimate for China could well be overstated. One way to look at it is a more regionalised approach, which would put China’s economic heartland provinces in the south-east into the WB high-income bracket. Given their significant GNI contribution, estimated economic losses for China as a whole would be reduced significantly.

It’s the market, stupid?

So how can we explain the disconnect between massive annual economic losses and the stock market’s reaction?

Well, the honest answer is, we can’t, but let’s give it a try nevertheless.

Equity markets tend to overreact. This is especially true in today’s highly indexed and automated trading world. Following a sharp decline earlier this year, markets are celebrating a variety of events. Multiple promising vaccine trials play a significant role in reducing the likelihood of a protracted pandemic lockdown. Reduced political uncertainty in the US certainly helped too, as did the measured approach in handling the second covid wave this fall.

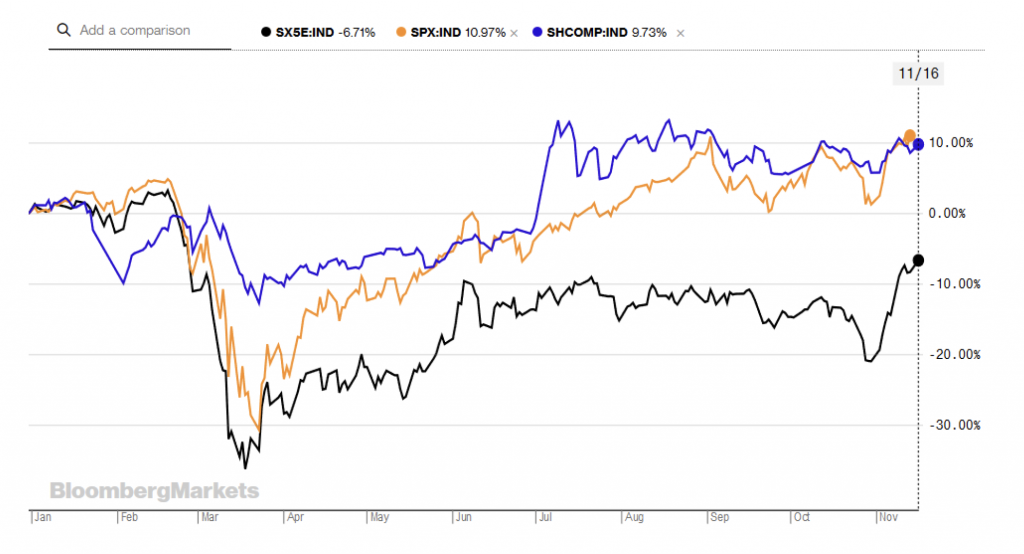

An interesting observation is the peak-to-trough volatility differentiation of various global market indices. Whereas the Shanghai Composite index showed only a roughly 15% peak-to-trough volatility during 2020, those of the S&P500 (~36%) and the EuroStoxx50 (~40%) are significantly more severe. This points to impact differentiation and a significant competitive advantage for those countries with effective pandemic counter-measures.

Where do we go from here?

Given the high social and economic stakes at play, pandemic prevention and containment preparedness must become part of the competitive advantage toolbox deployed by policy-makers as well as individual companies.

Economic losses caused by pandemics are on par with other high-profile economic threats like climate change (0.2-2.0% of global GDP at risk) or large-scale natural disasters (0.3-0.5% of global GDP at risk). All three are qualified as major economic disasters by the IMF with 0.5% or more of global GDP at risk.

However, while natural disasters and, in particular, climate change are declared frontline issues attracting both political attention and significant (public) funding, pandemic risk is not.

The World Bank and the WHO estimate that as little as US$1-2 per capita per year would allow for adequate preparedness while the US National Academy of Medicine estimates that investing an incremental US $4.5bn annually to be used primarily for strengthening national public health systems, funding R&D, and financing global co-ordination and contingency efforts would significantly reduce the severity of future outbreaks.

Comparing these investment propositions with the expected cost savings, winning the next ‘deal of the year’ award for effectively fighting a pandemic should be a walk in the park.