Cryptocurrency is something of a fairy tale, but the real story is one of central banks seeking financial repression by any means possible.

Arguably, the best background reading for global finance over the past 30 years was written by the Brothers Grimm more than 200 years ago. Particularly pertinent is the tale of Hansel and Gretel, a brother and sister abandoned in a forest, where they fall into the hands of a cannibalistic witch who lived in a house made of gingerbread. The metaphor of financial markets as an enchanted forest inhabited by mythical beasts, fantastic structures, luscious temptations and evil forces serves as a good primer for an aspiring student of today’s financial landscape. Indeed, contemporary fiction writers have been flummoxed in their attempts to contrive anything more surreal than the larger-than-life dramas unfolding before us.

If Western governments and their central banks had not opened the doors to this fantasy world, we would not have Tesla, Uber, risk parity, 60:40 portfolio management, quantitative easing, forward guidance, yield curve control, gold fanatics, central bank digital currencies, libra, stablecoins and cryptotokens, most notably bitcoin. Life would probably have been much harder for J.K. Rowling too.

What we have witnessed since the early 1990s is the spectacle of central banks being sucked into the machine of global finance, swapping a semblance of control over the financial system for a measure of influence within it. Central banks long to regain control, which explains their restless innovation of ways and means to influence their environment. Yet it is this very restlessness that describes the paradox of modern central banking: it is only by breaking its promises that it can gain traction on the financial system. Remember the jibe of a UK lawmaker to then Bank of England governor Mark Carney in 2015, likening him to an “unreliable boyfriend”.

There was an eruption of economic volatility and a derivatives crisis in 1994

Central banks earned their spurs, or are commonly thought to have done so, in the conquest of inflation in the early 1980s. Then, a decade later, there was an eruption of economic volatility and a derivatives crisis in 1994. Central banks redirected their firepower against volatility and instigated the NICE (non-inflationary constant expansion) decade that lasted until the run-up to the global financial crisis. The GFC threw a stake into the heart of the credit system, bringing bankruptcy, default and general misery. Central banks pivoted again to attack the new enemy of default with a strategy of lower-for-longer interest rates, followed by zero interest rates (and, for some, negative interest rates) and then outright financial repression through massive purchases of government debt and other assets. However, repression is not the same as control.

Successful financial repression is a play in two acts. In the first act, nominal interest rates fall across all maturities, whether for structural or policy reasons, and real bond returns are very pleasing. So much so, that it appears wise and safe to leverage them. After an interval of indeterminate length – certainly long enough for a swift G&T and a trip to the facilities – act two opens. When conventional wisdom holds that inflation is dead, that aggregate demand is much too weak to support rising inflation, that technology and demographics are deflationary forces, then the stage is set for an inflationary surprise.

Act two is all about unanticipated inflation. Back to the Brothers Grimm (but also recounted by Hans Christian Andersen), once the Pied Piper has led all the children (read bond investors) into the mountainside, then the door is closed. During act two, the investors watch, trapped by illiquidity, as all those juicy real bond returns are unwound.

Having led us into a fantasy world of zero interest rates, apparently low inflation, minimal defaults (global bankruptcies fell by 30% in 2020) and soaring asset values, central bankers should not be surprised by the popularity of gold, the rise of value-destroying enterprises (subsidised by credulous investors), and the emergence of existential threats to their monopoly on seigniorage and regulatory oversight of the payments system.

The removal of interest on bank deposits and income on investments provokes an indiscriminate search for yield on the one hand, and an appetite for unbounded capital risk on the other. In recent years, central banks have harnessed the power of the leveraged community to exert ever greater downward pressure on rates and yields. Yet, lest this feeling of regained power go to their heads, the merest glance over their shoulders will be enough to bring their chariot to a juddering halt, as in the ‘taper tantrum’ of 2013.

When yields, as well as rates, fall to (or even below) zero, then all the juice has been squeezed out of the bond market. The odds of securing further capital gains are unfavourable. Act one has ended. In the US and the UK benchmark bond yields have begun to rise, but in Japan they remain nailed to the floor.

As central banks experiment with the design of putative retail digital currencies (in the vanguard, the curiously named Bahamian sand dollar), their interest lies in creating a rock-solid unit of stable currency value, bearing zero or negative interest. Diem, seeking to be the market leader in stablecoins, is a private digital currency that sits inside the framework of global banking regulation, making a virtue of its compliance. Diem seeks to supplant Visa and Mastercard in the provision of merchant payment services. But bitcoin is a very different kettle of fish.

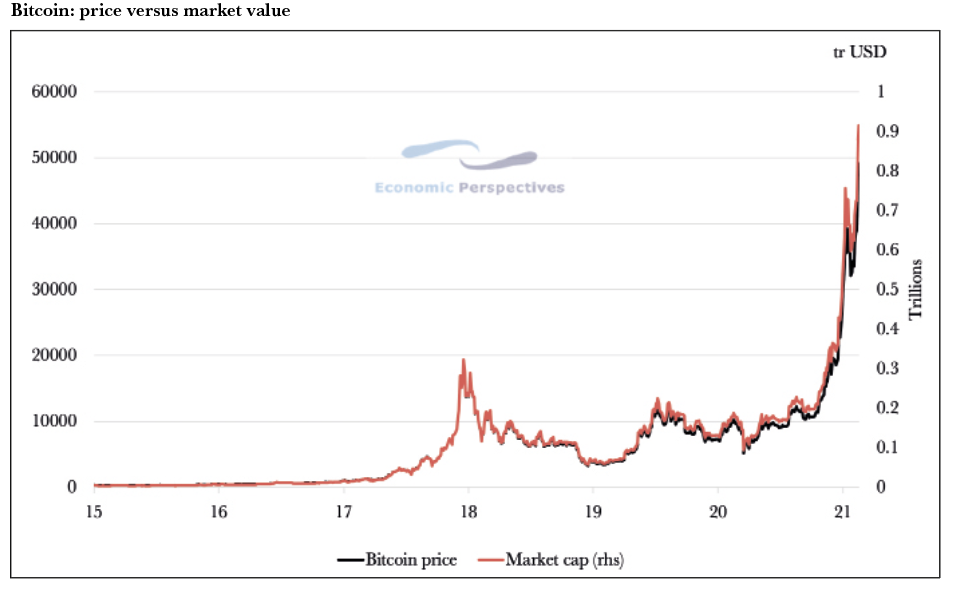

If gold is to central banking what kryptonite is to Superman, then bitcoin features as the twisted, vampiric Parasite, who feeds on energy to live. Since late 2017, when bitcoin lost more than 80% of its value, it has been assumed that the financial regulators would swat away the threat of bitcoin if ever it returned. To (almost) everyone’s surprise, bitcoin is back with a vengeance, winning daily endorsements, and central banks have been thrown onto the defensive.

Bitcoin is growing out of its libertarian ideal – obviating the need for KYC (know your client), snubbing regulatory approval and indifferent to its subterranean ESG (environmental, social and governance) status – and becoming instead a fully regulated, if speculative investment. Now that Wall Street has the scent of the profit pool that crypto-assets could become, the regulators are likely to focus their energies on the unregulated offshore exchanges where most of the criminality resides.

This modern fairy tale may yet have a few twists and turns in store, but the arrival of act two is clearly of critical importance. An explosive inflation would undermine the credibility of central banks – which continue to argue that the expansion of their balance sheets is non-inflationary – and would bolster the reputation and usage of bitcoin, whose leading attribute is its limited supply. The prospect of real estate transactions using bitcoin is far-fetched, notwithstanding the entrepreneurial activities of Baroness Mone in Dubai. However, bitcoin could be useful to diversify the risk of a property portfolio.

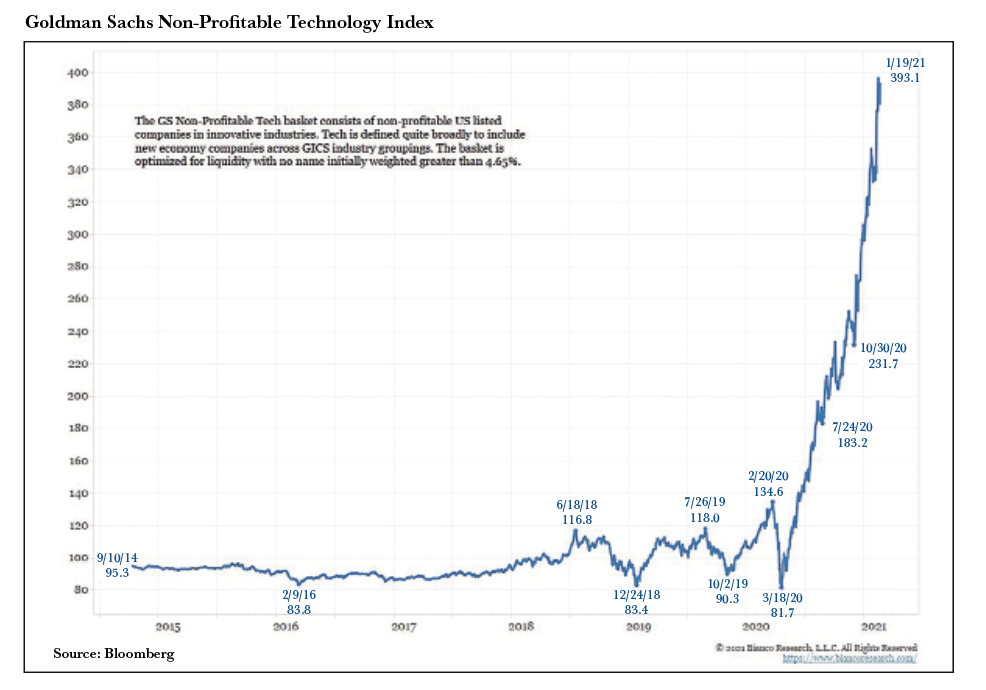

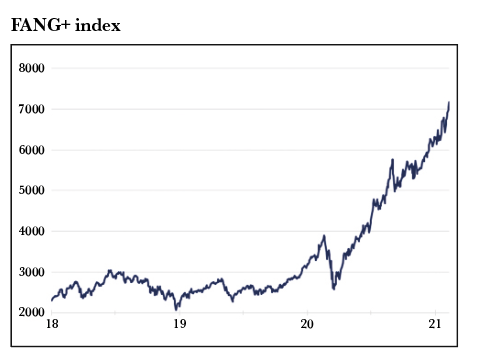

If hitching up to the bitcoin bandwagon feels like a monstrous risk, then it surely is. But loading up with government bonds when locked into a deflationary mindset; with Tesla shares, believing in the future of upmarket electric vehicles; with junk bonds in a blind search for yield; or with loss-making technology companies, in the hope that the future is brighter than we could ever imagine, are also examples of extravagant risk-taking.

Only when we have the perspective of history, and 1990-2025 is a completed fairy tale, will we be able to appreciate who were the plucky pioneers, who the fantasists, who the villains and who the visionaries.