For a year or more after the 2017 election, your columnist’s most frequently asked question from politicians, journalists and many others, was why the polls have remained so stable, in spite of all the political turbulence. That has completely changed in recent months, with the latest figures showing particularly dramatic moves. So what should we make of them?

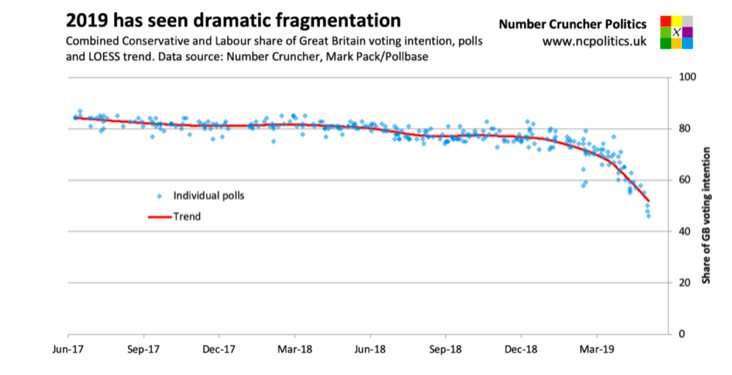

Importantly, both main parties have lost support recently. In 2017, the combined vote share of the Conservatives and Labour in Great Britain was 84.5 per cent (remember that polls usually do not include Northern Ireland, so the frequently cited figure of 82 per cent understates the extent of the fragmentation). Even as recently as the start of 2019 this figure was 76 per cent in the polls. But, since then, something dramatic has changed. Two of the three latest polls have shown the major parties’ combined share dropping below 50 per cent.

This is extreme by historical standards – the only precedent came at the height of the SDP search after the Crosby by-election in 1981, when the equivalent number was 46.5 per cent. That aside, there hasn’t been anything comparable to this level of fragmentation in Britain since polling began 80 years ago.

The latest drop has hit the Conservatives much harder. The last few surveys have been catastrophic for the party. Opinium’s numbers are the worst since 1997, ComRes’s the worst for 24 years. The numbers are so bad that comparisons have been made not just to the Conservatives’ dire performance in 1997, but to the 1993 Canadian election, which saw the Canadian Tories suffer a wipeout from which the party never recovered.

Yet Labour isn’t covering itself in glory either. The only poll to show the Conservatives doing worse than their 19 per cent in the latest ComRes results, from 1995, put Labour on an almost unbelievable 62 per cent. Today, ComRes puts their support at 27 per cent. An opposition party going backwards in midterm is never a good sign, but to do so when the governing party finds itself such severe difficulties is particularly worrying for Labour supporters.

As for where the votes are going, to state the obvious, the Brexit Party is doing extremely well – the aforementioned SDP surge in the early 1980s is really the only comparable performance by a brand-new party in recent times.

However, the Liberal Democrats are also picking up votes – the three polls conducted since the local elections have shown an average gain of five points for the Lib Dems nationally compared with the previous polls from the same pollsters, while YouGov’s London poll shows them gaining ten points in the capital since December. While it can be debated whether these gains are solely due to Brexit, it is clear that the movement is not solely on the Leave side.

So does this mean that the party system as we’ve known it since the Second World War is disintegrating altogether? There a few points to consider, each of which, to my mind, has a sound basis both in psephological theory and in the data.

One is that polling moves, particularly when driven by events, can overshoot. News is never more salient than when it’s hot of the press, and response bias is often at work too – people with strong views on the issue of the day are often likelier to respond to pollsters’ emails or phone calls. That’s certainly not to say that these latest moves are a blip, but I would wait a few weeks to see if there’s any correction before reaching any definite conclusions.

The second is that European and Westminster voting intentions tend to converge in the short-term, and that may be happening now. It is hard to say whether these are genuine but temporary alignments of voting intentions for European and Westminster elections, or a mirage caused by pollsters asking both questions in the same poll and unintentionally priming respondents. But it happened in 2009 and 2014, so even if we can’t assume it is creating misleading polls now, it is something that’s happened before.

Having said all of that, the third point I’d make is that the conditions have never been more conducive to a major realignment. The parties and their leaders are unpopular, but that fact is compounded by the fact that traditional loyalties are weakening just as new ones are strengthening. I can think of no precedent for an issue both as politically dominant as Brexit, which also cuts across party lines (in terms of their respective voter coalitions if not their MPs) to the same extent.

So while I would exercise caution over declaring this The Great Realignment for now, such talk is not absurd. History won’t stop the two main parties worrying about recent developments — and nor should it.