It is one of the most “identified” structural failings of the UK economy. A shortcoming, we are told, that lies at the core of why the UK will see no growth next year, and indeed more generally, why the British economy is the basket case of the globe’s leading economic actors. Of course, the matter in hand here is the “hopelessly weak” productivity of the UK labour market.

The question we ask in response to such claims is, if labour across the UK private sector is so terribly unproductive, why, for so long, has ever more been added, with workers paid ever more for their services? So much so, in fact, both employment and wage growth recently reached record-highs.

Addressing the above “conundrum”, are we supposed to believe employers within the UK are charitably/uncommercially hoarding labour and paying for “zombie” workers? Well, as explanations go, this is absurd; all the more so given how low redundancy frictions are within the UK private sector.

Could it be instead that somehow it is more affordable to use poorly performing labour than investing in fixed assets? Well, after years of an ultra-low cost of debt, this hardly explains matters; if labour could have been replaced, it would have been. For there would have been a shift from “manpower to machines” if the former were not doing a productive enough job.

There will no doubt be those claiming that its years within the EU’s single labour market gave the UK so much “cheap” labour, its private sector gorged upon it even in its least productive forms. The reality, however, is that as much as the UK did indeed draw in workers with comparatively modest education and experience, it also attracted those so highly talented, they raised the UK’s average labour productivity bar.

Now, might the reality actually be that the UK does indeed have a productivity problem, but one of a failure to properly measure it in the UK’s post-modern high value-added service and manufacturing state?

No doubt even with this argument, one will come up against criticism that zero-hour contracts and the general rise of the gig economy, have combined to create a host of unmeasurably low value “self-employment” jobs that no nation should want. The problem with this impression of the UK labour market is the degree to which jobs have been added in highly desirable sectors. Across all forms of tech – bio, fin, prop etc. – the UK has become the European hub and indeed a per-capita rival to the US. In engineering too, the UK has enjoyed a move up the value-added ladder, such that its cars and all manner of consumer and capital goods involve manning in unrivalled R&D centres.

For their part, the UK’s universities have spawned business and science parks as working homes of those whose output is close to impossible to capture. After all, how could one measure the daily output of a professional coding DNA for a future life-saving vaccine, or a programmer writing script for a world-beating piece of software, one whose launch lies ahead, and whose use will last for years? As for the idea such special staff are rare, this defies the data which shows their numbers have grown impressively.

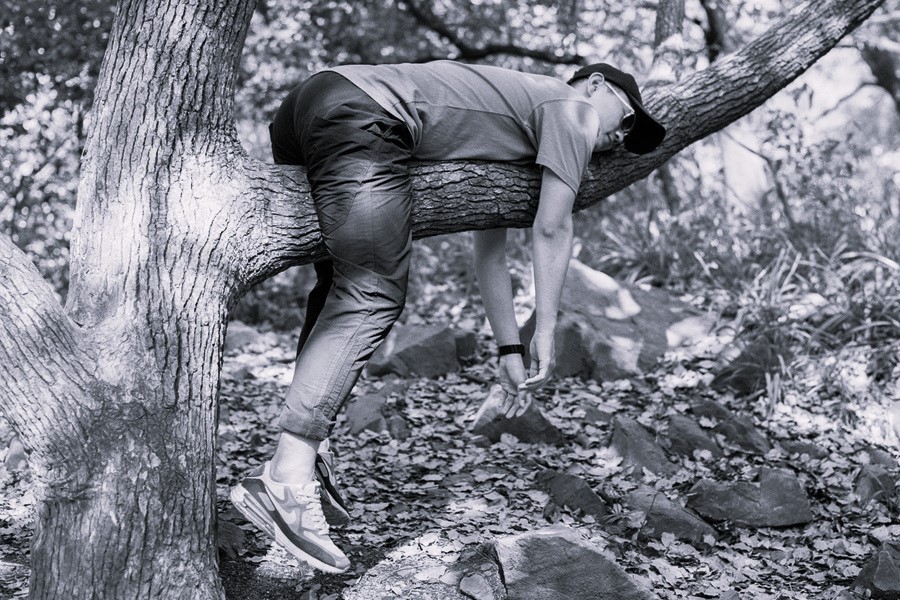

Let’s turn to an observation concerning productivity which all can see, but largely goes unmeasured; us being close to permanently connected to our work. One should consider this a net productivity benefit to employers, but it is one the ONS seems to miss in its estimations. It is more than unreasonable to claim that over recent decades of remarkable technological breakthroughs, the UK’s private sector workforce has failed to record considerable productivity gains. That we have failed to record these welcome advances in output per hour over recent times, speaks volumes about how unproductive the ONS itself is. And though we are incapable of putting firm numbers to how our time has become so much more productive over recent times, the idea it is not material is nonsense.

So, if we are not to recognise as accurate the official ONS measure of UK worker productivity, how can we possibly work it out?

Well, as is often the case, one should follow the money. Follow wage inflation, that is, and treat it as the clearest clue. After all, given their commercial instincts, one should expect firms to only pay their workers more if they produce more. True, there are many other factors at work. But no less true is that we have yet – and maybe measurement matters will improve in time – to accurately capture output across the UK’s vast service sectors. Because of this issue, we have no other real data option than to adopt a direct line approach. Look, that is, to impressive UK wage growth and pay awards as evidence of the productivity gains the ONS is failing to produce data for.