During the last four years, the prospects for freer world trade have been in retreat. Now, with a new broom about to sweep into the White House, there is renewed hope for progress both in bilateral and multilateral trade negotiations.

Financial markets have been focused on fiscal stimulus and the prospects for an effective covid-19 vaccine. They have yet to seriously contemplate the potential for the improvement in international trade and co-operation which might be seen during the next presidential term.

Before looking ahead, it is worth reviewing the current environment for global trade. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) was signed by 23 countries in October 1947. It was transformed into the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in January 1995 and has grown from 123 members to 164 nations today.

The WTO serves three functions: the provision of a negotiation forum to liberalise trade and establish new rules; the monitoring of trade policies: and resolving disputes between members. In all three areas it has been facing challenges which long predate the arrival of the current pandemic.

The WTO’s Appellate Body and dispute settlement system are in particular crisis since they were effectively suspended in December 2019 after the US blocked appointments, leaving the Appellate without a quorum of adjudicators. US concerns, which have also been voiced by a number of other WTO members, need to be addressed.

The WTO needs to establish new rules for dealing with digital trade and e-commerce, and it must also strive to deal more effectively with China

The dispute settlement function is closely linked to the negotiation function. This is also in crisis. Finally, the nature of global trade has changed significantly over the past 25 years, and WTO rules have not kept pace. Effective and efficient dispute resolution is of international importance. In a February 2020 paper entitled Structural Change and Global Trade, the Federal Reserve observed that the ratio of world trade to GDP increased from 19% to 48% between 1970 and 2015. Over the same period, however, services rose from 50% to 80% of that expenditure. The authors conclude that structural change (increased consumption of services rather than manufactured goods) has reduced global economic growth substantially over the past forty years.

The European experience

Over the past decade, in a similar vein to the US, across the EU a consensus has been forming that globalisation went too far. This view has only been strengthened by the covid-19 crisis, where a shortage of medicines and medical goods, such as PPE, reinforced the opinion that Europe’s citizens must be protected by reshoring production. Recent research by ECIPE – the European Centre for International Political Economy – finds this consensus to be built on erroneous foundations in that Europe’s principal trade is with itself.

They identify just 112 products (1.2 % of total imports) for which the four largest suppliers during the recent crisis were non-EU countries. This compares with 2,000 products for which the four largest suppliers are EU domicile. They were unable to identify a single covid-19 related good for which all EU imports came solely from non-EU countries. ECIPE recommends that the EU, rather than reshoring, embrace more open international trade to create diversified and robust supply chains.

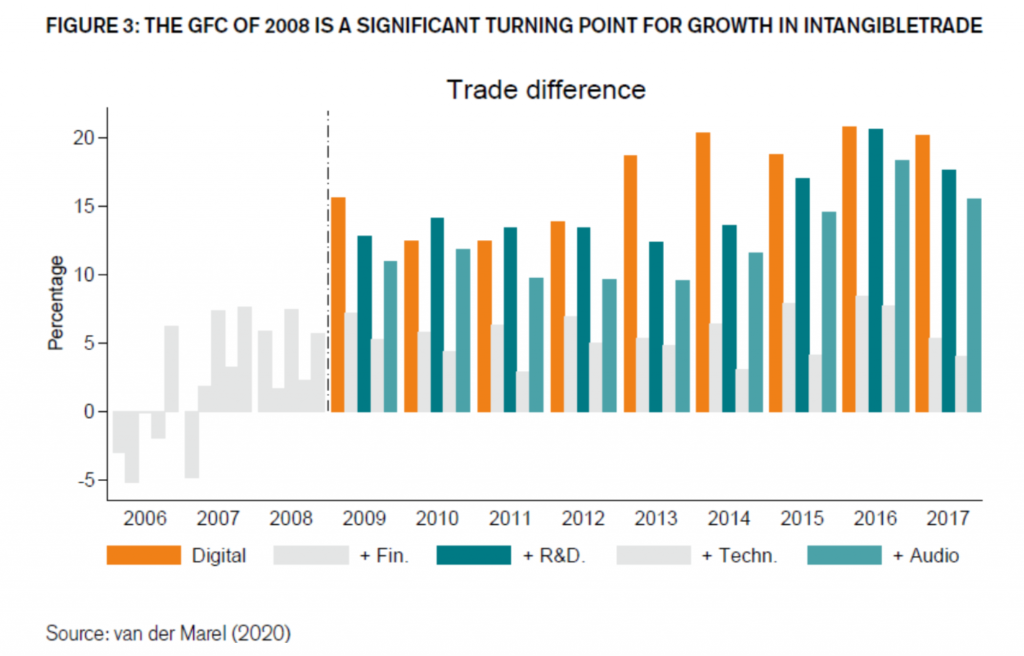

In Globalization Isn’t in Decline: It’s Changing, ECIPEpicks up on the same theme as the Federal Reserve, noting the transformation of trade from manufactured goods towards services. This chart shows how the structure of global trade has evolved since the great financial crisis:

The next chart shows the overall picture more clearly:

The WTO needs to establish new rules for dealing with digital trade and e-commerce, and it must also strive to deal more effectively with China and other high-growth, mercantilist economies, particularly in contentious areas such as state-owned enterprises and industrial subsidies. There are other goals, such as environmental sustainability, which could also be progressed. For the present, however, the organisation, which, by some estimates, has raised more people out of absolute poverty than any other in the history of mankind, is no longer fit for this purpose.

The first step towards reform requires an agreement on the definition of a ‘developed’ as opposed to a ‘developing’ country: self-designation is open to widespread abuse. Then there are the issues of transparency and compliance. A complete overhaul is in every nation’s interest; on this, at least, the US and EU are generally agreed. The devil, naturally, is in the detail and the largest gulf between the two economic giants revolves around reform of the Appellate Body. Even if the US and EU manage to agree to work together, however, the WTO still requires China to actively engage; it is the world’s largest trading nation and without its commitment, reform will be futile.

From a purely economic perspective, multilateral tariff reductions among all members of the WTO is preferable to bilateral agreements. In an August 2020 op-ed published in The Wall Street Journal, US trade representative Robert Lighthizer described his strategy for How to Set World Trade Straight, arguing that, in many cases, free-trade agreements (FTAs) perpetuate protectionism and undermine the core WTO principle of most-favoured-nation (MFN). So much for the theory; in practice, since the WTO’s creation in 1995, almost all tariff reduction has been effected via bilateral FTAs, the number of which has tripled since 2000.

RCEProcity

How likely is WTO reform? This question should be linked to the likelihood of the new Biden administration focusing on trade. In their election campaign, the Democrats indicated that they would not negotiate any new trade deals before first investing in American competitiveness at home.

Throwing down the metaphorical gauntlet, however, earlier this month (and after a decade of wrangling) China signed the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), an alternative to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) which the US signed in 2016 (President Trump pulled the US out) – and from which China was excluded. The new deal – which itself excludes India, which has a massive trade deficit with China – has been signed by the members of ASEAN together with Japan, South Korea, Australia and New Zealand.

The RCEP group of countries, with a combined GDP of over $26trn – roughly 30% of the global total – 25% of global exports and a third of the world’s population, make this new FTA more than just symbolic. Global trade appears to be moving on despite the US and EU. The RCEP deal aims to reduce a range of tariffs on imports over the next 20 years, reducing costs and time for companies within the bloc. It meets some WTO commitments and fixes a number of regulatory objectives. There are dedicated chapters covering small and medium-sized enterprises, e-commerce, dispute settlement and technical co-operation between member countries.

Without WTO reform, economic nationalism

and trade protectionism will continue to

rise and with it global poverty

RCEP is not the first ‘Asian’ FTA, following in the wake of AFTA, SPARTECA, SAFTA, BIMSTEC and the TPP, and it is also more of a harmonisation exercise than a radical push to end protectionism. However, it is estimated that it will increase world income by $200bn and add $500bn to world trade by 2030. This is enough to compensate for the entire cost of the recent US-China trade war. It is a sharp wake-up call for the new US administration. President-elect Biden’s response to the news was immediate: “We make up 25% of the world’s trading capacity and we need to be aligned with the world’s other democracies so we can set the rules of the road instead of allowing China and others to dictate outcomes because they are the only game in town.”

Biden’s appointment of Antony Blinken as head of the US State Department also bodes well for foreign policy in general; the sooner the US becomes reengaged the better. The pandemic prompted serious questions about China’s dominance in global manufacturing, especially in sensitive sectors such as rare earth minerals and medical supplies. It has also heightened the tension between China and the West over technology transfer. In response to the pandemic – and the truncation of global supply chains that it precipitated – import-substitution policies have been introduced by many developed and developing countries, along with a significant increase in state aid. These policies need to be rolled back as the global economy normalises in 2021.

Without WTO reform, economic nationalism and trade protectionism will continue to rise and with it global poverty. Supply chain disruption will become a permanent feature rather than a temporary inconvenience. The US and EU need to drive negotiations forward; Japan, the UK and Canada (among others) are obvious allies in this process. China must be engaged along with other key manufacturing countries such as India and Brazil.

Back in July, in testimony before the US Senate Committee on Finance – entitled “The United States Needs a Reformed WTO Now”– Jennifer A. Hillman, Senior Fellow for Trade and International Political Economy, Council on Foreign Relations and Professor, Georgetown University Law Center concluded: “Given the global economic pain from the coronavirus pandemic and the likely emergence of a post-pandemic wave of protectionism, the world needs a strong and effective WTO more than ever. Successfully confronting a rising China with its state-run economy also requires a fully functioning WTO. The best way to achieve that is to start by fixing the dispute settlement system which underpins the rules-based trading system. Doing so will require US leadership that moves beyond simply tearing the Appellate Body down. Now is the time to rebuild it. A revitalised dispute settlement system can then serve as a catalyst to broader reforms of the WTO itself.”

Conclusion

The Sino-American trade war and the covid pandemic have damaged the cause of free trade, but hanging onto the coattails of technology, the nature of trade has actually been in transition for more than a decade. Trade in intangible services is expanding rapidly. As economies and industries digitise, demand for these services will continue to expand. Barring government measures to impede this growth, trade in data and information services has the potential to support an enormous improvement in economic wellbeing globally. Those countries that attempt to shield themselves from the new global economic exchange will suffer, while those that embrace change will thrive.

The incoming US administration has many issues to confront in the wake of the worst economic event in decades, but the benefits of freer trade should not be overlooked. A return to the pre-covid world is impossible, but indiscriminate trade wars benefit no one. At 78 years old it is generally expected that Joe Biden will be a one-term president, and this presents him with a golden opportunity to embrace reform in many areas of policy. He has been afforded the chance to leave a lasting legacy: an overhaul of the WTO is one such reform.

This article was originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research.