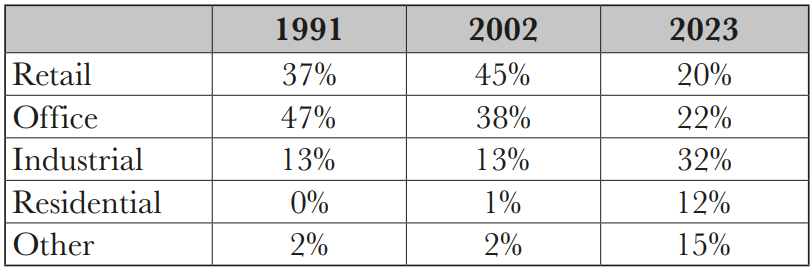

Property fund managers are currently under significant pressure. The current higher interest rate environment, sustainability necessities and the macro and micro impact of technology have all delivered challenges. More fundamentally, their core business has shifted, and it is not obvious that they are all equipped to cope. In brief, their core business used to be retail and office (85%) and industrial (15%). This has shifted towards beds (residential), and eds and meds (social infrastructure, or ‘other’ in the table).

UK sector weights, 1991-2023

These emerging residential and social infrastructure sectors have become increasingly popular with investors, and some have matured into core real estate investments, such as purpose-built student accommodation (PBSA). However, this shift is problematic for real estate fund managers: the emerging sectors are more management-intensive than they are familiar with.

Designing and running an operational asset requires constant re-commissioning, tenant engagement, the development of tenant apps and so on. This leads either to operationally competent fund managers, or to close co-operation with operators. This partly explains why Greystar is a successful manager, as their experience of operating their residential assets feeds back into their development design, and also explains why the right operator can command a rental premium.

Common among all operators – including owner operator – are two things:

Firstly, they deliver space as a service, and space as a service is concerned with the occupational management of real estate assets. Space as a service has developed as an idea alongside the concept of the shared economy and the returns created by more intensive short-term use of space. With the appropriate software, a space offering which is fractionalised by time can be offered to a large marketplace, with economies of scale justifying heavy investment in high quality UI/UX. This idea is a long way from the traditional long lease to a single tenant, which requires very little expenditure on innovation and customer service.

As a direct outcome of the above, operators control building performance. Smart building technologies are being utilised to provide information about building performance, or to directly facilitate or control building services addressing social sustainability criteria such as occupant wellness, productivity and satisfaction, as well as building energy performance and waste reduction. This drives the sustainability agenda.

The emergence of modern operators will put them in control of both the customer relationship and the building performance, facilitating the integration of sustainability economics. Shifting from a B2B to B2C model in real estate will create branded spaces, such as we see in the hotel market. There will be Marriotts and Hyatts in the worlds of working, living, wellness, entertainment, healthcare, student living and life sciences to add to the existing branded hotel and shopping centre operators.

Investment managers will need to consider very carefully whether they wish to become operators themselves. An investment manager could reasonably be expected to develop operational expertise in the provision of retail space, just as a housing rental company can develop expertise in the design and operation of residential space. But an investment manager should not reasonably be expected to develop operational expertise in the provision of specialist service areas like hospitals or schools. And there is a grey area in between. For example, should an investment manager operate a hotel?

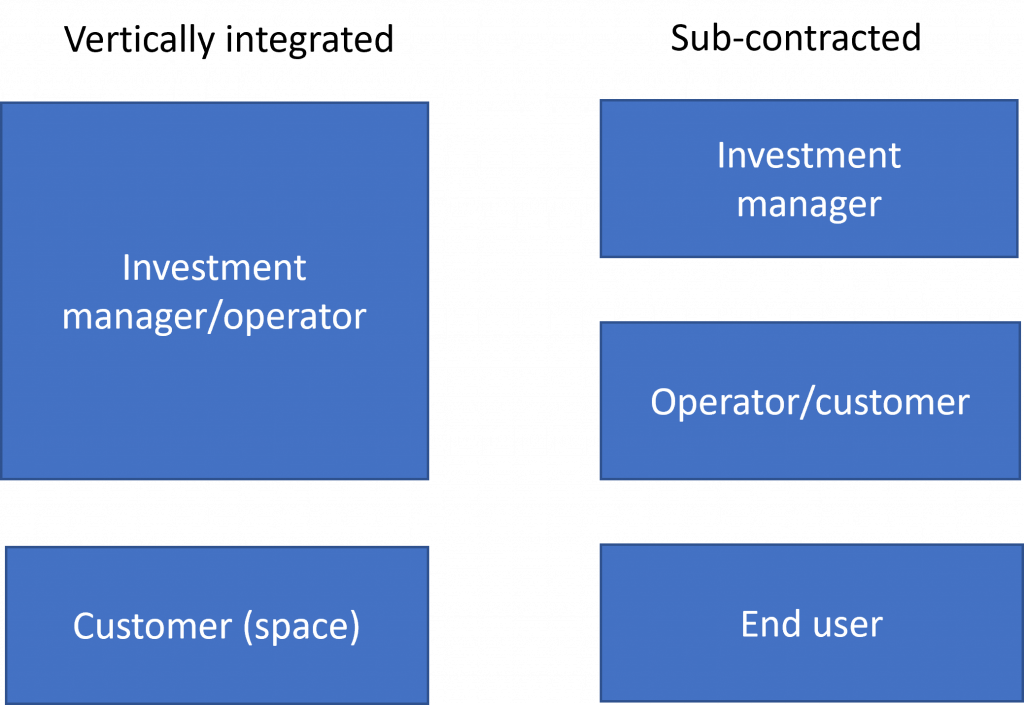

Integrated and sub-contracted operations

This challenge leads to alternative operational models. The vertically integrated investment manager/operator can be observed where space is something of a commodity in office, industrial/logistics, shopping centres, retail parks and the high street, and in private rental housing. In these sectors the customer is a buyer of space rather than a buyer of specialist services.

This model is less likely but possible in social housing, student housing, co-working space, self-storage and data centres. It is highly unlikely in hotels and social infrastructure uses such as care homes, medical and educational property, forestry, energy generation and any emerging real estate, real asset or infrastructure sector in which space management has yet to become a commodity. In these sectors operational management will have to be sub-contracted, and the end user is remote from the investment manager.

Hence, managing mixed use real estate will lead to the so-called hybrid model, where an investment manager grows or buys operational teams in certain verticals in-house and outsources operations in others, like, say, Blackstone. It seems to us that in addition to the hybrid model there are two other credible models for the interface of investment management and operational management.

Sub-contracted operations

Property managers may attempt to evolve into operators and continue to provide sub-contracted services to investment managers. This is the least disruptive trend for the market. Examples would include CBRE launching its co-working space brand HANA, followed by a large investment in Industrious, the largest operator of co-working space in the U.S.

It seemed a surprising move to many, but it looks highly logical, as it has helped CBRE to evolve from a traditional property manager to an operator which has a deep understanding of building and customer requirements in a specific property type.

In this increasingly operational property world, multi managers and other indirect specialists are set to thrive. Under this model, operator selection is a core skill, while asset and operational management are very deliberately out-sourced.

Specialist, vertically integrated manager/operators

New generation specialist investment managers will start to emerge from operators of niche spaces. As operator expertise becomes a core skill in a specialist sector, an investment management business can be built around it. This is a market threat for investment managers competing for LP capital. Observing this trend, other investment managers will go deeper into operational excellence (arguably, as Hines, SEGRO and Prologis and newcomers such as Matter have done).

Traditional investment managers can protect themselves from becoming obsolete by investing in operating businesses at the start-up stage, or by developing a deep expertise in operator selection and partnership. As ever, innovation will deliver rewards.