Originally published October 2021.

The returns are still valid.

Looking at the global investment landscape today, there is a gaping hole where dependable fixed interest assets used to be. Successive rounds of central bank purchases have annexed much of the territory that pension, life insurance and collective investment vehicles formerly occupied. Deprived of income yield and duration, investors have pursued multiple strategies attempting to recoup what they have lost, without assuming excessive market risk.

Many have doubled down on the corporate debt of commercial and industrial companies, emboldened by the utterly remarkable interventions in these markets by the US Federal Reserve last spring. Their enthusiasm has crushed corporate credit spreads to the point where there is virtually zero compensation for default risk, notwithstanding the extent of balance sheet leverage and despite the cyclicality of some of the companies concerned.

Others have piled into securitisations of residential and commercial mortgages, real estate debt and consumer loans, judging that expansive central bank purchases of government debt will provide solid support for private sector debts also.

“Those who put their distributions in peril by engaging in heavy CapEx or corporate acquisitions are punished accordingly”

Still others have sought to replicate bond-like characteristics in the equities of dividend-paying blue-chip companies – so-called ‘bonds in drag’. Institutional investors have

made plain to the managements of these companies that payouts must not only be maintained, but must increase over time. Those who put their distributions in peril by engaging in heavy CapEx or corporate acquisitions are punished accordingly.

However, an important and obvious substitute for government fixed interest is commercial and residential real estate: not the debt securitised against the assets, but the assets themselves. While real estate investment trusts (REITs) offer an attractive route to indirect property investment, the sector is relatively small and niche. Real estate holding companies are mostly micro businesses created by individuals for tax reasons. Largely missing from the landscape are mega-cap real estate asset management companies with diversified commercial and residential property holdings.

In global equity market terms, real estate is a Cinderella. Sectoral, backward-looking price-earnings ratios, as computed by Refinitiv Datastream, identify financials and real estate as the lowest-rated of all equity sectors. While the global P/E for healthcare is 31.8, technology 31 and consumer discretionary 28.3, the rating for financials is 12 and real estate 13.4.

However, hidden beneath these aggregates are some remarkable and significant anomalies. Foremost among them is the real estate P/E in the US, of 50.5. In Italy it is 45.7, Australia 31.3, UK 29.8 and Spain 29.3. Some smaller countries, such as Romania, Bulgaria, Greece and Malta have similarly exalted ratings, and likewise in Asia (India, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines) and South Africa. It appears that investors are disregarding the pandemic-related depletion of earnings and keeping faith with their real estate investments.

In some of these countries, including the US, the real estate sector is more highly rated than the technology sector. While it is commonly supposed that the US market P/E is inflated by its large weighting to technology, in fact it is the real estate and consumer discretionary sector P/Es that provide the greater boost.

The broader context to the reappraisal and re-rating of real estate companies is the phenomenon of real yield suppression that was discussed in this column last quarter. The combination of stupendous central bank purchases, regulatory coercion, collateral requirements and bond market convexity has created a US Treasury bond market that no longer responds in predictable fashion to inflation or fiscal shocks. Meanwhile, negative real interest rates are a fertile breeding ground for leveraged property investment.

The leading central banks are playing a high-stakes poker game. No matter how strong the post-Covid economic rebound, policymakers are loathe to tighten the policy stance – by first tapering and then reversing asset purchases and raising rock-bottom interest rates. What is at stake is the negative bond-equity correlation that has stabilised portfolio returns over the past 30-plus years. Throughout this era, with few exceptions, the contemporaneous correlation of bond and equity prices has been negative. But with 10-year bond yields so close to (or below) zero for so many governments, there is negligible scope for bond prices to rise as an offset to an equity price correction. Indeed, in the light of recent inflationary departures, the prospect of bond and equity prices falling in tandem must be keeping central bankers awake at night.

When equity markets crashed in 2000, retail investors flocked to residential property; when the markets halved again in 2008-09, they did the same. Should equities slump again in 2021-22, it is reasonable to expect that this reflex will kick in again.

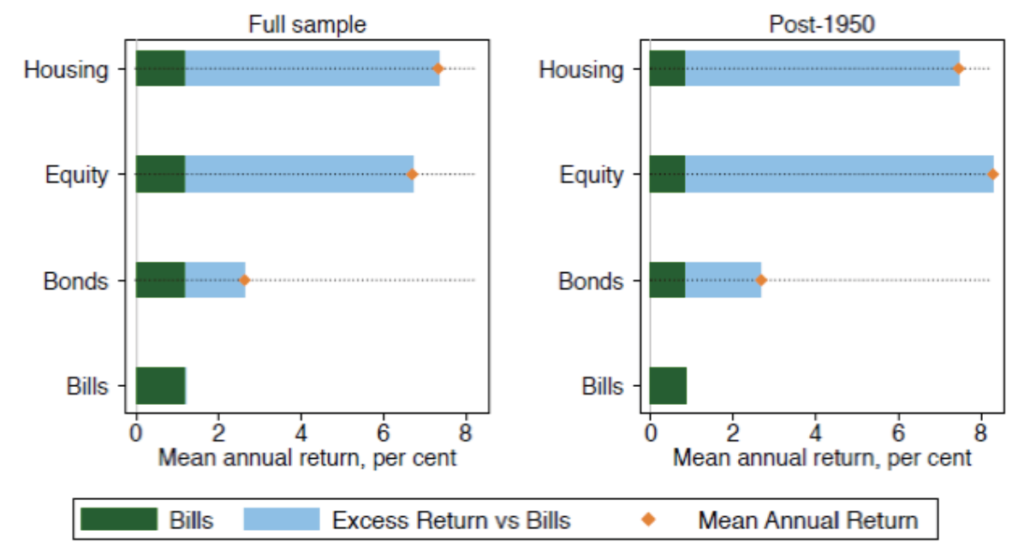

A study carried out at the San Francisco Fed with the modest title, ‘The Rate of Return on Everything, 1870-2015’, sounded a ringing endorsement for the inclusion of housing in institutional portfolios. Examining data for 16 countries, the authors’ key finding is that residential real estate, not equity, has been the best long-run investment in modern times (figure 1). Although the real returns on housing and equities are similar, the volatility of housing returns is substantially lower.

While long-run capital gains on housing are relatively low, around 1% per annum in real terms, and considerably lower than capital gains in the equity market, the rental yield component is considerably higher and more stable than the dividend yield of equities, so that total returns are of comparable magnitude.

To the objection that transaction costs are much higher for housing than for bonds and equities, the authors respond that average holding periods for housing are much longer than for comparable financial assets. Thus, their transaction cost estimate of an average 7.7% of property value would be incurred every 10 to 20 years, making only a small dent in average annual returns.

Moreover, the low covariance of equity and housing returns reveals the scope for significant aggregate diversification gains. Last year, my colleague Yvan Berthoux carried out some experiments using US data, incorporating housing in hypothetical investment portfolios. Since 1973, he discovered that a 40/40/20 equity/bond/ housing portfolio generated only slightly lower annualised real returns (6.9% versus 7.3% for the traditional 60/40 equity/bond allocation), but with significantly less volatility (5.7% versus 8.2%), giving a better Sharpe ratio and much smaller maximum drawdowns over six and 12 months.

On the specific sensitivity of real asset returns to inflation, the US housing market has generated average annual real returns of 5.6% when CPI inflation was above 6%, while equity returns evaporated when inflation rose above 4%.

Figure 1: global real rates of return

Notes: arithmetic average real returns pa, unweighted for 16 countries. Consistent coverage within each country: each country-year observation used to compute the average has data for all four asset returns.