The Restaurant Group (which I’ll shorten to TRG) joined the model portfolio in early 2016, shortly after the company published some very upbeat 2015 results.

Revenues were up 8% while earnings and dividends per share were up 13%, continuing the company’s long track record of impressive results.

But then things started to go wrong in its core restaurant business (TRG also runs pubs and airport concessions, and these continued to perform well).

Initially this was put down to operational issues, such as a lack of focus on value and service. But despite operational improvements over the next couple of years, like-for-like sales continued to fall.

By mid-2018, management admitted that TRG’s problems were structural rather than cyclical.

Key problems included reduced footfall at restaurants in out-of-town retail parks (thanks to the shift to online shopping), increased competition from other branded restaurants, new food delivery aggregators (e.g. Just Eat) and increasing costs such as the minimum wage, rent and business rates.

Management’s solution was to acquire Wagamama, a high growth pan-Asian restaurant chain. This would bring economies of scale and allow TRG to convert underperforming sites into Wagamamas.

However, Wagamama does not solve TRG’s fundamental problems which are, in my opinion, a lack of competitive advantages, a tendency to sign long leases and (thanks to Wagamama) high debts.

For these and other reasons I have decided to sell TRG this month, with the following less than stellar results:

Investment results

Purchase price (adjusted): 257p on 11/04/2016

Initial position size: 3.9%

Sale price: 137p on 05/11/2019

Holding period: 3 years 7 months

Capital gain: – 46.9%

Dividend income: 15.7%

Annualised return: – 12.0%

The slowing UK economy revealed TRG’s underlying weaknesses

Note: You can download the original pre-purchase review (PDF) which was published in the April 2016 issue of my monthly newsletter.

Obviously this is not a great result, so in the rest of this post-sale review I’ll focus on TRG’s underlying weaknesses and how they became much more visible after I began lease-adjusting ROCE (returns on capital employed) a couple of months ago.

But first, here’s a quick review of this investment from beginning to end.

Up to 2015, The Restaurant Group had producing rapid and extremely steady growth

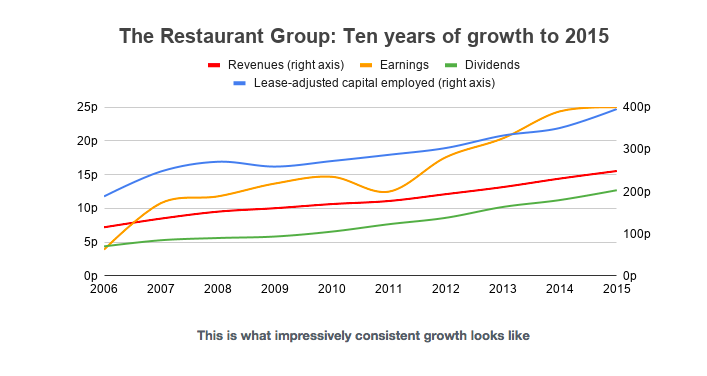

When TRG joined the model portfolio in early 2016, its track record was almost second to none. Revenues, earnings and dividends had increased almost every year over the previous decade, giving the company an average annual growth rate of 10%.

This growth had been driven primarily by an increase in the number of restaurants, food-focused pubs and airport concessions operated by the business, from a total of 284 in 2006 to more than 500 in 2015.

Overall TRG looked like a very strong business, with high profitability (average returns on capital of 19%), well-known brands, very little debt and no pension liabilities. The valuation multiples looked attractive too, with a 4.4% dividend yield to go along with its ten-year average dividend growth rate of 12%.

This is what impressively consistent growth looks like

Of course, it wasn’t all good news otherwise the dividend yield wouldn’t have been so high.

The company’s 2015 results mentioned economic uncertainty from the Brexit referendum, an increase in competition from other branded restaurants and pubs, and a decrease in footfall at some of its out-of-town retail park sites thanks to the growing trend for online shopping.

Another headwind was costs, with above-inflation increases to the National Minimum Wage and the introduction of the higher National Living Wage. These negative factors had already led to a like-for-like sales decline of 1.5% and a near-50% decline in TRG’s share price (before it joined the portfolio).

Management’s opinion was that most of these factors were either short-term or could be dealt with by providing a better service, improved menus, improved efficiency and reduced costs through technology.

At the time, my opinion was that people weren’t going to stop eating out, so any revenue or cost pressures would be reflected across most of the restaurant and pub industry. In fact, given TRG’s impressive track record, I though these pressures might squeeze some of its competitors out of business which, in the long-run, would be good for TRG.

But that isn’t how things turned out.

A surprisingly rapid decline, bordering on collapse

Less than a month after TRG joined the portfolio, management announced that they expected 2016 like-for-like sales to be down by 2.5%. This was due to ongoing challenges in revenues (from declining footfall at out-of-town retail parks) and expenses (from increasing rents, wages and other costs).

At this point the company launched a comprehensive review of its strategy and, somewhat surprisingly, the CFO left with immediate effect. This was surprising, to me at least, because CFO and CEO “resignations” usually occur after much more than a 2.5% like-for-like sales decline.

Clearly there must have been more going wrong than just a minor sales decline.

Despite all this, management still expected to open around 30 new sites in 2016, reflecting their continued belief that TRG’s ultimate goal of 850+ UK sites was still achievable.

And then, in August 2016, the CEO left with immediate effect.

Investors found out why in the company’s 2016 interim results: Like-for-like sales were down 4%, 33 sites had been identified for sale or closure and the balance sheet value of another 29 sites was being written down (leading to a significant loss for the year).

The strategic review was ongoing, but eventually it would evolve into a plan to:

Re-establish the competitiveness of the restaurant brands

Serve customers better and more efficiently

Grow pubs and concessions

Build a leaner, faster more focused organisation

The replacement CEO reiterated this turnaround plan in the 2016 annual results and again in both the 2017 interim and annual results.

By the end of 2017, results from the turnaround plan were minimal. The number of meals served had gone up, but revenues from the restaurant business were down, and good results from pubs and airport concessions were not enough to offset the decline.

Related: 2018 Performance review and lessons learned

Management continued to execute on the turnaround plan throughout 2018 and like-for-like sales continued to fall. With ongoing cost pressures and a focus on value (i.e. lower prices), margins were squeezed and profits remained at less than half their 2015 highs.

Despite all the hard work, it looked like the turnaround plan was not working.

Management throw in the towel and acquire Wagamama

Shortly after the 2018 interim results, management effectively threw in the towel and announced that TRG was to acquire Wagamama, a fast-growing pan-Asian restaurant.

The price tag was £357 million, or £559 million including Wagamama’s debts, and the acquisition was funded primarily by shareholders via a rights issue (I chose to sell the allotted rights rather than take them up).

I say management “threw in the towel” because once the Wagamama acquisition had been announced, they stopped focusing on turning the existing restaurant business around. Instead, the turnaround plan was replaced with a plan to:

Convert suitable existing restaurants into Wagamamas

Close at least 50% of the company’s restaurants as their leases expired

Grow Wagamama

Grow pubs and concessions

Wagamama, with its healthier menus, better locations, existing links with delivery aggregators (e.g. Deliveroo) and generally “trendier” brand, must have looked like a get-out-of-jail-free card to TRG’s management.

However, the combination of TRG and Wagamama is not something I want to be invested in, and here’s why:

An alternative history: The Restaurant Group as a company with little or no competitive advantage

In the late 1990s, TRG (or City Centre Restaurants, as it was then) had most of its restaurants in high footfall locations such as high streets and tourist centres. It had 45 Garfunkel’s restaurants (with about half in airports), a handful of other brands and was the UK’s leading Mexican restaurant operator.

The economic boom of the late 90s saw the casual dining market explode, with new restaurants opening up left, right and centre. When the bust of the early 2000s arrived, the combination of an oversupplied market and an economic downturn gave TRG two years of losses.

At this point, the company decided to focus on out-of-town retail and leisure parks.

In theory, these parks had significant barriers to entry. For example, a retail/leisure site might have five retail stores, two restaurants (one run by TRG), a cinema and a gym. Once these tenants are in place, the ability of additional restaurants to appear on site is very limited compared to a high street, so TRG would have a captive market of shoppers and cinema-goers.

This sounds good in theory, but my revised interpretation of this strategic switch is that TRG did not have a meaningful competitive advantage on the high street, so it moved to where there was less competition.

This strategy worked from around 2001 to 2015. During that time the company expanded enormously, putting restaurants in dozens of new retail parks and leisure parks that were springing up left, right and centre.

Eventually sites for new out-of-town parks became limited, so developers expanded existing parks. Where there was one restaurant, suddenly there would be two more.

TRG leased many of these new sites, sometimes having two or three of its restaurants in a single retail/leisure park, competing against each other. This kept headline growth going, but it also reduced profit margins and returns on capital.

By 2015 the out-of-town casual dining market had become saturated too, while wages, rents and other costs continued to go up. As in the 90s, TRG was unable to hold onto its profits in a saturated market, at the end of a boom, and with economic headwinds instead of tailwinds.

So my opinion of TRG is that it is a company with little or no competitive advantages.

It has spent at least the last 25 years looking for the next dining trend to ride, from high street casual dining to out-of-town leisure park restaurants, and from Mexican food to Wagamama’s pan-Asian cuisine.

This has worked well when it’s found the right trend to ride, but it means TRG’s future depends on management’s ability to spot the next big thing, where growth is high and competition is low.

In other words, TRG’s future depends on a single decision (i.e. what trend to ride) every ten or twenty years. That makes it a massively risky business compared to a company that has been selling basically the same thing in more or less the same way for many decades.

As for Wagamama, perhaps is is the next big thing, but then again perhaps it isn’t. All I know is that Wagamama has more liabilities than assets, makes little or no profit and has £225 million of debt.

That may be okay if you’re looking to invest in the next big thing, but I want to invest primarily in companies that are already the “big thing” in their chosen niche.

Unfortunately then, this investment is set to make a loss. That means the only way to benefit from it is to learn the relevant lessons and apply them in future to make better investments and avoid similar situations.

Lesson 1: The three most important things in retail investing are leases, leases and leases

The biggest lesson from TRG is this:

If a business is heavily dependent on rented property then analysing lease obligations is critical because they’re essentially the same as debt obligations.

Picture this scenario: A retailer leases a store on a five-year agreement, with rent set at £10,000 per quarter. The retailer now has the right to use that store and has an obligation to pay the landlord £10,000 every quarter.

Another retailer leases a store on a five-year agreement, but pays the landlord all the rent up front. The landlord gives a discount for paying upfront, so the retailer pays £150,000 instead of £200,000. The retailer doesn’t have that much cash, so it borrows £150,000 from a bank. The bank charges interest, so the total amount to repay is £200,000. This is repaid through 20 quarterly payments of £10,000 over five years.

Related: The 2018 stock market correction and the art of being patient

In both cases the retailers have the right to use a store for five years. They also both have an obligation to pay £10,000 per quarter. The only difference is that the first retailer pays the landlord while the second retailer pays the bank.

In both cases the rights and obligations are virtually the same, which is why lease obligations are effectively the same as debt obligations. And if that’s the case, then lease obligations should be taken into account as if they were a debt.

For example, let’s look at return on capital employed, where capital employed is the sum of shareholder capital (shareholder equity) and debt capital (borrowings).

The right to use a rented property over several years is a capital asset which has been funded by an obligation to pay the landlord. This makes the lease obligation a form of capital funding, so the outstanding lease liability should be included in the calculation of capital employed along with the other sources of capital funds, i.e. shareholder equity and borrowings.

In other words, when we’re calculating returns on capital employed, we should lease-adjust capital employed. If we do that then the picture for TRG changes dramatically.

The Restaurant Group’s returns on lease-adjusting capital employed were consistently terrible

In addition to average shareholder equity of £158 million and average borrowings of £58 million, TRG also had average lease liabilities of £580 million between 2006 and 2015. This turns its average capital employed of £216 million into an average lease-adjusted capital employed of £796 million.

This reduces the company’s average net return on capital employed of 19% to an average net return on lease-adjusted capital employed (ROLACE) of 5%.

Having added ROLACE to my investment strategy and stock screen in October, I now expect my investments to have produced an average ROLACE of at least 10% over the last ten years. So by that standard, TRG’s 5% is a terrible rate of return.

It suggests, which I now think is correct, that TRG had no pricing power and no meaningful competitive advantages. If I’d looked at lease-adjusted capital employed in 2016 then this enormous red flag would have stopped me from investing in TRG in the first place.

The main reason for TRG’s large lease obligations is their length; in 2018, 82% of its leases were longer than five years and 34% were longer than ten years. This is a problem because it reduces flexibility.

For example, if footfall, revenues and profits permanently decline in one of TRG’s restaurants because the retail park in which it’s situated adds another three restaurant units, TRG won’t be able to renegotiate its rent or close that site for perhaps five, ten or more years.

Even worse, if the lease is longer than five years then rent is typically subject to upwards-only increases which are at least in line with inflation.

Lesson 2: A lack of information is usually a bad sign

Unlike TRG’s restaurant business, its pubs and airport concessions have been performing quite well. Total pub numbers have gone from from 49 in 2013 to an expected 88 by the end of 2019, while total concessions have gone from 60 to an expected 81 over the same period.

And in recent years TRG’s pubs and concessions generated more profit than its restaurant business, so strategically they’re second only to Wagamama in terms of importance.

If TRG’s pubs and concessions had sufficiently attractive results, in terms of profitability, lease obligations, margins and so on, then there’s a chance I would have decided to hold on rather than sell.

However, I have no idea how much revenue or profit these businesses make, or what leases or other assets and liabilities they have, because TRG’s management don’t think this is something investors would be interested in.

Why that’s the case I have no idea, but TRG provides no “segmented” results in its annual reports at all. Investors left to work out the details with nothing more to go on than the number of pubs and concessions.

To be frank, this is shockingly bad investor relations. The restaurant, pub and concession businesses are significantly different, so why aren’t their results shown separately?

How is an investor supposed to work out the strengths and weaknesses of the pub and concession businesses without this information?

In early 2016 I was comfortable buying TRG with such limited information, but I have learned a lot in the three and a half years since then.

One thing I’ve learned is that I want to have a far more detailed understanding of a company before investing in it, which means seeing the results broken down to a useful level.

TRG doesn’t provide a useful level of detail in its annual reports, and that lack of information makes me feel uncomfortable with the investment. And if I don’t feel comfortable with an investment, I don’t want to own it.

Plan, do, check, adjust

Obviously it’s disappointing to lose money on an investment, but the important thing is to focus on the big picture, apply the relevant lessons and keep moving forwards.

In this case, TRG has provided me with important lesson about lease obligations and accounting transparency, and a reminder that companies relying on “big wins” (e.g. picking the next big dining trend to ride) are almost always more risky.

As usual, the proceeds from the sale of The Restaurant Group will be reinvested into a new holding next month, with an initial position size of around 4%.