More people, more growth

Longtime Random Walk readers know that babymaking and people-growth (and/or the lack thereof) are very important things.

It’s pretty simple, really: if you want to grow productivity, then grow the number of productive people you have.

- Productive people make things, like businesses and families, and consume a lot of things, while they’re at it.

- They are both supply and demand.

- The more you have, the more you grow.

Now, you might say “well sure, but you can also just make the people you have more productive.”

That’s true, and we should do that.

However, those gains are hard to keep to yourselves. And if you’re optimizing for comparative advantages—or relative productivity—then simply making your workers more productive may not be enough. Others will simply learn from your ways.

But having more (productive) people?

That’s a comparative advantage that can’t easily be copied.

In fact, there’s some evidence that “having more people” or specifically, “having more working age people” explains nearly all of the comparative advantages among Western or Advanced economies.

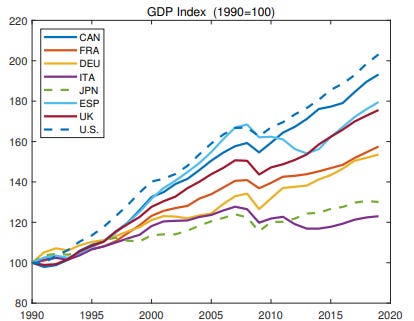

Consider first, GDP growth since 1990:

The US (dashed blue line) looks pretty good—we lapped the field when it comes to growing. Italy (purple) and Japan (dashed green), not so much.

Yay, USA! We’ve got the secret sauce! So, what’s our secret?

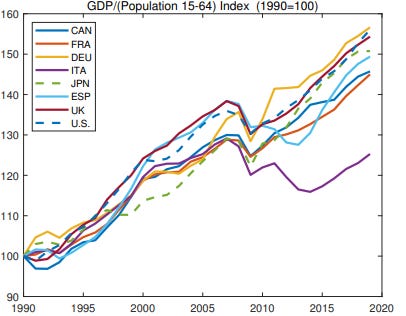

Well, look at GDP per working age population:

Hey, where’d our field-lapping go? All the lines look almost the same.

Italy is still a disaster, but everyone else is much more tightly clustered and, and in fact, Deutschland took a slim lead.

In other words, when you control for how many working age people we added, it turns out the U.S. is not the best (and the field is a whole lot closer than we thought).

So, to reprise the question, what’s our secret sauce? Is it culture? Is it the air? Is it governance?

Nope. It’s none of those things.

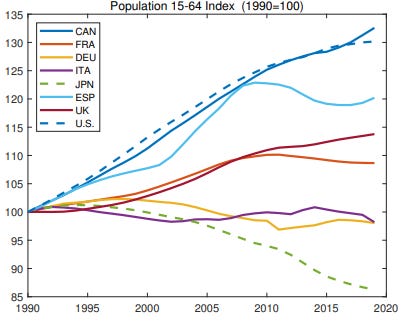

It’s this (mostly)—people, just people:

We (and Canada) steadily grew our working age populations, and no one else did, or did as vigorously.

That’s one heckuva demographic tailwind. It’s a good thing 30 years of people-growth isn’t ending, right?

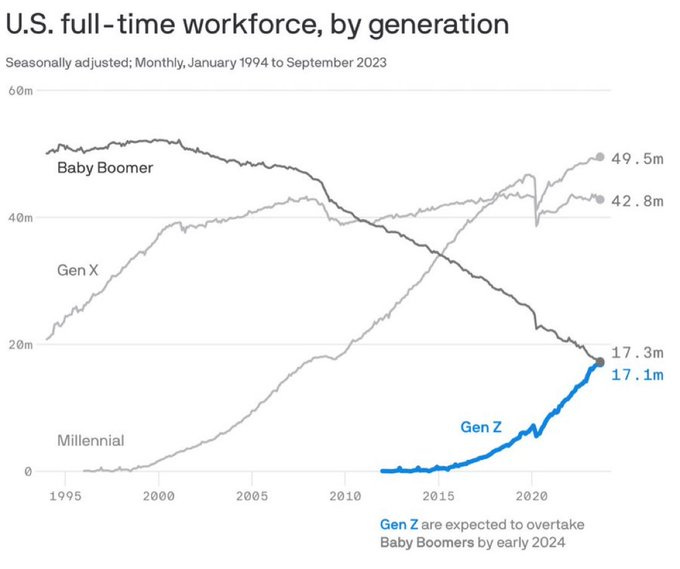

Here’s another way to cut it, looking at the US workforce specifically, by generational share:

Steep Gex-X growth (doubling from 1995-2000), followed by steep Millennial growth, followed by steep Gen-Z growth.

Gen-Z is, of course, a smaller generation than Millennial, and given Gen-Z’s recent outlook on well, anything, there’s reason to expect even fewer reinforcements after them.

It can’t be stressed enough: it’s babymaking time.

This article was originally published in Random Walk and is republished here with permission.