Sometimes reality bites back at Trump, but not always.

During the 2024 campaign, the stock market typically reacted favourably to good polling news for Donald Trump, and it surged after he won. But since Trump took office, the stock market has been down quite a bit, lower than it was before the election. This is not the biggest crash in American history, but it is notable.

It’s particularly notable as a reaction to a Republican administration; it’s not like the news has been dominated by aggressive action against climate change or pollution or some other non-GDP measure.

Instead, we’ve seen that despite their hyping of DOGE as a fiscal policy measure, the GOP has no intention of balancing the books.

And we’ve seen a lot of tariff news. At first, I thought the tariff news looked basically good to financial markets. Trump said a bunch of crazy things about taxing Canada and Mexico, but then delayed that for a month in exchange for minor concessions. But the success of that bullying strategy emboldened him to try more bullying, and the past three weeks have seen a flurry of on-again, off-again tariff action and foreign retaliation that is very confusing but broadly points in the direction of higher barriers to trade.

This behaviour has been bad news for the economy.

But it’s been particularly bad news for one theory of Trump’s behavior, which is that he knew on some level that his campaign rhetoric about tariffs was dumb but enjoyed it as a kind of troll. In reality, Trump seems to be genuinely torn between some level of deference to market judgment and a sincere desire to plow forward with an aggressive and nonsensical trade policy.

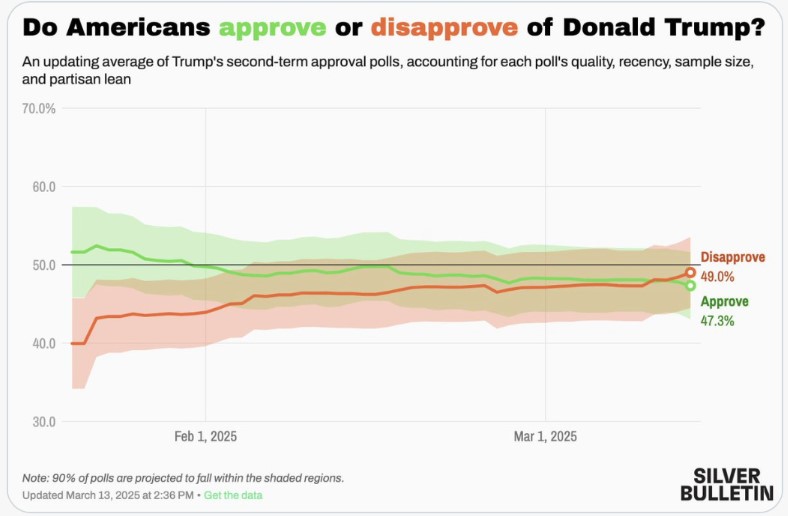

As a result, stock market sentiment has turned negative. Consumer sentiment has turned negative. And worries are mounting that in addition to the genuine supply shock Trump is dealing the economy, we could find ourselves in a spiral, with falling stocks leading to consumers pulling back and a decline in real economic activity. Not coincidentally, Trump’s poll numbers have declined sharply after a transition period that went much better for him than his first.

This all serves as a reminder that reality really does matter in the political process. It’s not that Democrats’ anti-Trump messaging suddenly got much better (high-profile infighting about senate procedure is not a great message) or that Trump lost his flair for commanding attention.

It’s that having become president, he’s now making governing decisions, and some of those decisions blow back in big, consequential ways.

Politics isn’t just a battle of memes or a war of attention; some things people are going to notice, no matter what. This applies to trade and to a lot of other big-picture stuff, like Republicans’ ongoing efforts to cut hundreds of billions of dollars in Medicaid benefits. I hope that won’t happen, but if it does happen, the unavoidable political reckoning can’t just be spun away. And even in advance of it happening, we’ll see things like stock market movements that impact hospitals and provider lobbies yelling and screaming about the negative effects on their livelihoods and their patients. The system works, to an extent.

What worries me, though, is all the corrosive actions that won’t necessarily generate short-term, highly salient blowback.

Bad presidents scatter land mines

The nuclear deal that Barack Obama struck with Iran was politically contentious at the time of its enactment.

And yet, when Donald Trump took office, it was not seen as a given that he would reverse it. Most of his national security team, in fact, seemed inclined to accept that having made the deal, formally tearing up the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action would only make things worse. But Trump forged ahead and did what his pro-Israel supporters wanted, ripping up the deal and making a pretty bold and aggressive bet that Iran wouldn’t respond by dashing for a nuclear weapon and that America’s international partners, in creating the sanctions regime that led to the JCPOA, probably wouldn’t abandon the whole thing in the short-term.

This bet proved correct.

Everyone more or less stayed chill, letting Trump notch a win with no blowback, and figured they could try to just outlast him. Then, Joe Biden won the election, and his team set about seeing if they could re-open talks with Iran.

- They found that the Iranians, reasonably, didn’t want to strike another deal with a Democratic administration that would swiftly be torn up by a Republican administration, so they demanded bigger concessions than they got from Obama.

- Biden, reasonably, knew that Obama’s deal had been politically tough and didn’t want to bend over backwards to give Teheran a better deal with zero cover.

- Discussions broke down, and as a result, US-Iran relations are worse than ever.

I don’t want to say that this breakdown was the cause of the 7 October attacks in Israel or the Houthi shutdown of Red Sea shipping that we’ve been dealing with ever since those attacks. But it was a contributing factor. Trump’s actions on the JCPOA set into motion a series of events that fully unfolded only after he left office. Now, of course, he’s back in office, Iran is closer than ever to a nuclear weapon, and Trump is sending letters threatening them with war. It’s totally unclear where this will eventually land, but all of the possible outcomes are worse than if Trump had behaved more responsibly in his first term. But that term-one call was a sort of delayed-fuse issue — the consequences were quite bad, but they manifested over time in a way that made it hard for Democrats to capitalise on them electorally.

More broadly, Trump’s conduct during his thus-far-brief second term is already encouraging things like Poland exploring a nuclear weapons programme.

That would be a big step for them, or for any country, and as with backing out of the JCPOA, the consequences of Trump encouraging nuclear proliferation will likely be felt over a period of years without an immediate backlash.

And while, in the short-term, a friendly country developing nuclear weapons is hardly a huge crisis, the reality is that every additional nuclear power, no matter how friendly, raises spillover risks and makes it more likely that unfriendly countries go nuclear, too. The odds of real catastrophe over the medium and long term are going up, and these long tail risks are probably not priced in to most voters’ immediate thinking.

The worse, the better?

I mention these unpriced risks because I have decidedly mixed feelings about the prospect of further economic deterioration. So far, the stock market decline is just a stock market decline. But falling share prices could lead to falling consumer spending and business investment and an actual recession. That would genuinely cause a lot of suffering.

During Trump’s first term, my sincere preference was for Trump to make good decisions and avert human suffering.

This time around, I certainly don’t hope for anyone to suffer, but I am kind of glad to see Trump making flagrantly stupid calls that crash the stock market rather than operating in evil genius mode.

Because while swing voters ultimately decided that they didn’t care about 6 January, it certainly changed my view of Donald Trump. The fact that he was utterly unrepentant, re-obtained the GOP nomination, won election, and then pardoned the rioters is incredibly disturbing. He’s paired those moves with things like purging the Justice Department’s public integrity division, dropping charges against Eric Adams for inappropriate reasons, having the US Attorney for the District of Columbia repeatedly menace the First Amendment, deploying immigration law to attack free speech, and otherwise attacking the foundations of the rule of law.

Trump is not the first president to step on some of these red lines, and he won’t be the last. But 6 January and the 6 January pardons are a truly unique piece of contextualising information about the president’s priorities and the character of his inner circle that I find genuinely menacing.

And yet it’s clear that, unfortunately, this is not a compelling message or narrative for swing voters. What’s worse, business community elites don’t react to this kind of information with “yikes, Trump is scary, we need to check him to preserve American liberty.” They tend to react with “yikes, Trump is scary, we need to bandwagon with him.” So I don’t even like to talk too much about the threats Trump poses to American institutions because I don’t want a self-fulfilling prophecy. But I am kind of glad that Trump has opened his term not only with things that are long-term corrosive like politicizing the FBI, but also with things like the tariffs that generate an immediate short-term feedback loop.

Governing matters

Beyond the specifics of Trump, though, one thing that I think this shows is that the quality of governing decisions actually makes a difference.

I’ve been involved in a million debates about what polling says and whether politicians should take popular stances on issues. And while I think it’s important to get those questions right, I also think the answers are actually pretty boring and obvious. The much more interesting and nuanced question is how to wield power well. My guess is that a lot of Trump’s tariff lines — taxing foreigners and making stuff here at home — sound good to people. But what he’s actually doing is creating a huge mess, and it’s not the kind of mess he can hide.

I think the congestion pricing situation in New York is an interesting and more positive example of this. The big problem with this initiative is that it was very unpopular. That said, it did have two virtues:

- Congestion pricing is actually a good idea on the merits; it works pretty well and it raises revenue efficiently.

- It’s not like there’s some secret alternative approach to dealing with the MTA budget crisis that everyone would have loved.

Eventually, New York implemented congestion pricing despite the polling, and it keeps getting more popular over time because it works.

The main way Kathy Hochul could improve on the politics is by reforming the MTA so that it’s less of a wasteful money pit. But this, again, is actually a technical question of policy design and governance, not a question of position taking. Obviously the right thing for any candidate for office to say is that the MTA has bizarrely high cost structure and that someone should fix it. The interesting and difficult part is actually fixing it.

By the same token, on Election Day 2020, Joe Biden had a huge advantage over Trump as the candidate who’d do a better job of handling Covid. But by the end of his term, people were also mad about Biden’s handling of it — the dilemmas posed by the emergence of the Delta variant (and others that followed) were substantively difficult, and Biden’s team didn’t have broadly acceptable answers.

Meanwhile, nobody seems thrilled with Democrats’ anti-Trump tactics or messaging, but he’s bleeding support anyway, largely because of economic chaos and also because I don’t think most people actually want radical restructuring of the federal government.

This does not single-handedly solve all of Democrats’ political problems, because they also need to improve the public’s view of themselves.

But the deeper point is that while some of Trump’s actions will provoke sharp backlash, others won’t — including certain actions that will be very harmful on the merits. It’s probably worthwhile for everyone, myself included, to spend a little less time thinking about how to “fight Trump” and a little bit more about how to actually fix things, pick up the pieces, and deal with the aftermath. On the specifics of foreign aid, I think there are some pretty clear good ideas. On tariffs, Congress needs to pass laws preventing the president from radically altering trade policy on a whim. But how do we come back from the collapse of the western alliance system? How do we rebuild the civil service if federal employees don’t actually get job stability in exchange for limited financial upside?

These are hard questions, and I’m interested in looking for answers. I also think in many cases, there unfortunately may not be good solutions — some damage can’t be fixed, at least not any time soon, and that’s what makes this moment so scary.

Originally published by the Slow Boring and reprinted here with permission.