…and from place to place.

Part one of a three-part mini-series written by economist Savvas Savouri.

If I were seeking an analogy for how best to forecast what awaits the UK economy, it would be meteorological. To wit, a weather forecast is pointless if it fails to deliver geographic detail. Yes, there are moments ahead when all are set to bask in sun, be snow covered or suffer showers. These shared moments are, however, rare.

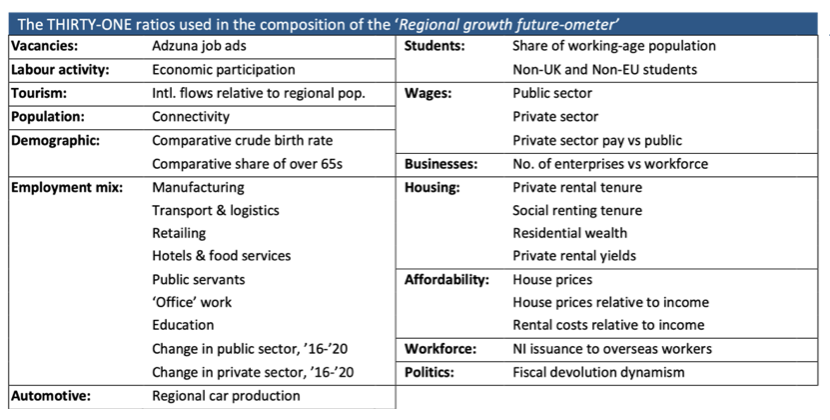

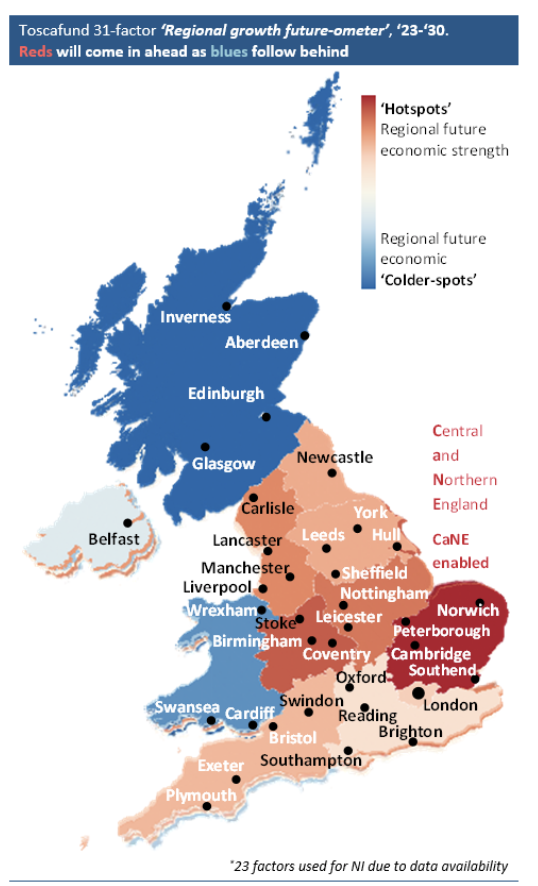

It is in drawing inspiration from weather forecasts that this series presents a taste of our economic projections for the UK’s regions out to 2030. It does so in the form of colour-coded heat maps, which illustrate where, over coming years, the UK’s economic hottest and coldest spots will be. The singular ‘Regional growth future-ometer’ has been created by factoring in 31 wide-ranging measures. These capture regional demographics, housing, labour markets and other spatially distinct dimensions that determine economic growth. We are convinced these measures taken collectively light up clear flare-paths for where the economy is heading in aggregate, and all the more intriguingly, how this progress will be spread across the country.

To repeat then, the 31 dimensions mapping regional DNA are blended together to create the ‘Regional growth future-ometer’. Across this map, shades of red indicate comparatively strong economic strength, while hues of blue suggest relative trailing fortunes. It has come about without prejudice or, in empirical speak, without any conscious attempt at data mining. Indeed, the colour conclusion presented has gone through rigorous sensitivity analysis, during which process we saw a remarkable consistency in ‘final complexion’. To be clear, the colour coding is relative. Blue does not imply economic decline, merely the expectation of more moderate growth than where shades are more blush.

Our regional projections should be seen in the context of an economic outlook where the UK writ large performs well, consistently growing ahead of expectations. We claim that the nature of the UK’s regional economic growth After the Dislocations (AD) we have all faced will be materially different from before Brexit and Coronavirus (BC) and prove different from place to place across the UK. Our forecasts suggest the UK economy will grow without interruption out to 2030. As things stand, there is nothing standing in the way of this despite exogenous shocks seen already in 2022.

While we could have chosen to make future changes in the measures identified as key structural drivers of economic growth different from their ‘historic spreads’, this would have defied reasonable logic. We have opted for the more sensible option of assuming future progress in UK macro-variables – car-making, logistics, higher education et al – to be distributed pari passu across it. Take, for instance, UK-based car and component making. While regions with little or no automotive industry could conceivably quickly begin to develop such, this is possible, but very far from likely. Far more probable is that increased car and component production – notably the manufacture of electric batteries – will come from existing and nascent capacity where there is an established automotive-making tradition. After all, there is compelling commercial logic for new car and component-making plants to be added proximate to existing infrastructures. The same reasoning of new capacity being located close to where it already exists applies to manufacturing more generally, and is relevant too for expansion in logistics and warehousing.

The pari passu argument aside, our ‘Regional growth future-ometer’ does make allowance for future regional fiscal devolution. When the latter arrives as it must, we will see an entirely new regional tax landscape – for households and businesses alike – across the UK. The rolling out of differentiated tax rates by existing and entirely new elected and fiscally empowered assemblies will materially move us. Another moving prediction we make is that where universities expand to a point that suitable real estate close by is either unavailable or affordable within reason, they will not stop growing, but grow somewhere else – taking their naming rights, for instance, from London to regions beyond it but still close.

I, of course, accept that some readers will have a very different view of what factors best work as determinants of what economically drives the UK’s regions. That said, we are more than happy to recreate the ‘Regional growth future-ometer’ with any and all modifications. For the record though, we need to stress this: any suggestions of what to use instead of/in addition to our factors need to be made in the context of its reliable availability at the regional level – a test our 31 factors comfortably pass.