EPRA’s new best practice recommendations for NAV calculations, which kick in this January, introduce three discrete NAV measures to replace the old ones. Are you ready?

It is well known that the UK listed sector (in aggregate) currently trades at a significant discount to underlying NAV. This masks sharp divergences between sectors, and management teams, but is true of the two bellwether stocks Land Securities and British Land, which are used by generalist investors to gain exposure to the sector. The key questions to be asked are, firstly, which NAV calculation is used, and secondly, is NAV the only/optimal valuation measure for UK REITs throughout the cycle?

The purpose of this article is to look at the recently announced changes to recommendations on best practice for NAV calculation from EPRA (the European Public Real Estate Association). These will be implemented for accounting periods starting 1 January 2020. A second article, next quarter, will look at alternative (non-NAV) valuation measures, which are used globally to determine if they have relevance to the UK, and who would be the winners and losers from these methodologies.

The UK uses IFRS accounting standards, which include mark-to-market valuations of assets. It also has a highly regarded valuation system, a long (more than 30 years) data series of valuations of assets in the direct market, a highly regarded valuation profession and a so-called Red Book that contains the rules and best practice guidelines for undertaking these valuations to ensure consistent application across the profession. What then, could possibly go wrong? In short, two things:

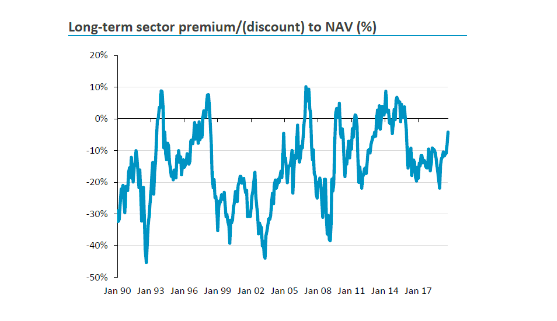

- Share prices do not have a consistent relationship with the valuation of the underlying assets (see chart 1). They range broadly from a 10% premium to a 45% discount.

- Not everyone calculates their NAV in a similar manner.

Chart 1: Long-term sector premium/(discount) to NAV (%)

The best way to answer the first point is not to take a forward-looking share price and compare it with a historic property valuation. This can be easily resolved by professional investors who have access to brokers’ forecasts and can compare the current share price with the forecast NAV in a year or two’s time, or indeed with the expected trough.

The best way to address the second point is to adopt a common standard by companies for reporting NAV. Sixteen years ago, EPRA introduced its Best Practices Recommendations guidelines for calculating NAV. Investors know that comparing a Landsec EPRA NAV with a British Land EPRA NAV would be comparing apples with apples.

Officially, there used to be two NAVs in the previous guidelines, namely: EPRA NAV, with the underlying assumption of a ‘going concern basis’, and EPRA NNNAV (‘spot’ fair-value NAV), which included mark-to-market adjustments. However, there have been several issues arising when, despite best intentions, the NAV did not reflect either the value of the business or the price at which the assets could be sold, for a variety of reasons. A current example would be secondary/tertiary shopping centres or retail parks, where aggregate demand is limited and assets are put on the market to reduce leverage (with the aim of being sold in a relatively short timescale).

As a result, following extensive discussions with investors, accountants and the companies themselves, EPRA has now replaced its NAV and NNNAV measures with three new specific NAV measures:

- net replacement value (NRV), which aims to represent the value required to rebuild the entity and assumes that no selling of assets takes place

- net tangible assets (NTA), which is focused on reflecting a company’s tangible assets (excluding goodwill and so on) and assumes that entities buy and sell assets, thereby crystallising certain levels of unavoidable deferred tax liability

- net disposal value (NDV), which assumes an orderly sale of the business, netting off the deferred tax, financial instruments and any other liabilities.

All three start from the same point – IFRS equity attributable to shareholders – and companies will be expected to show they transition from EPRA NAV/ NNNAV to these new three metrics. The disclosure of all three is compulsory, so that none of the three new metrics would lose prominence (as happened with the EPRA NAV and EPRA NNNAV).

Why the change? In our view, there are several reasons why a single NAV figure (be it EPRA NAV or EPRA NNNAV) is no longer deemed enough, most of which relate to corporate strategy and the divergent growth rates of the underlying assets. The listed sector used to be relatively simple: most companies operated a broadly buy/develop and hold strategy. Now, because of sharply divergent growth rates among the underlying assets, the varying levels of operational risk/management expertise required, and gearing levels, there is a sharp valuation divide between those companies forced to sell assets to reduce debt in the short term and those companies building a scalable presence in a preferred sector of the market.

So, who will benefit from these changes? Well, a lot of attention will be given to which of these three metrics a company considers most applicable to its corporate strategy. For instance, those that are building a platform and have a clear competitive edge in terms of critical mass might argue that NRV is the appropriate measure. This could include companies that have traded or are currently at a premium to EPRA NAV because of superior growth prospects and the fact that they represent critical mass and provide investors with a liquid way of participating in a specialist sector.

An obvious example in this category is Tritax Big Box, which has built up a 31m sq. ft larger-scale logistics portfolio, currently valued at just £4bn with a weighted average unexpired lease term of more than 14 years and a significant development pipeline. This is a highly focused and desirable portfolio, which would be impossible to replicate. Similarly, the Unite Group has built up a UK student accommodation portfolio of 51,200 operational beds with a total value of £5.5bn, of which Unite’s share is £3bn, again with a secured development pipeline for further growth. It may be the case that when one looks at the true value required to rebuild these entities, for example, the NRV figure is higher than a traditional NAV and therefore the share price rating appears less demanding than if a standard NAV was applied.

And which companies might opt for NDV? There has been a lot of market speculation regarding public-to-private transactions and the acquisitions of Intu and Capital & Counties in particular. The NAV figure that private buyers (be they private equity funds or sovereign wealth funds) would start with for their calculations would be NDV, which assumes an orderly sale of the business, netting off the deferred tax, financial instruments and any other liabilities. This would provide the platform to underwrite a transaction and determine the level at which an offer should be pitched. This might be lower than a standard NAV.

In summary, we believe the introduction of these new EPRA NAV calculations is an enormous step forward as it will allow investors to determine and differentiate between:

- the value of the operational business

- the value of the tangible assets in the business

- the break-up value of the business.

As a result there should be greater granularity around market pricing, with the appropriate NAV being applied to the appropriate corporate strategy.