Those gazing into the future should be wary of inflationary storm clouds.

There is cash in the bank, cash flows that are almost within touching distance and there are cash flows that are barely visible to the naked eye. Then there are cash flows that are merely figments of the imagination. Extraordinary by-products of the Covid-19 era are the miraculous improvement in investors’ eyesight and the mind-bending expansion of their imaginations. In other words, there has been a stampede into long duration assets, including so-called growth stocks, corporate credit and government bonds.

It is as if the investment mainstream had put on a virtual reality headset and entered a world that was in a permanently disinflationary state. In the absence of the inflationary threat, there was no reason to believe that interest rates would ever rise again. A competition began among investors to look further and further into the future. Those that could see the furthest were naturally willing to pay the highest prices for the securities that represented valid claims on these income streams.

“It seems that long duration assets are vulnerable to inflationary persistence even in a world of unusually low interest rates”

Then central bankers started to deploy the very same VR headsets, seeking to gain understanding of market psychology. Soon, they too entered this virtual world of permanent disinflation, bordering on deflation, and became terrified of ever raising interest rates again. Or reversing their substantial injections of liquidity.

Investors were delighted, as these very low interest rates were adopted as the appropriate discount rates, lifting the present values of these distant cash flows even higher. Vincent Deluard, of StoneX, estimates that about half of the expected value of US large-cap stocks will be realised after 2032. The long duration segment of the US equity market is over-represented in consumer discretionary (think Tesla), utilities, biotech and real estate. The long duration rally accelerated when 10-year bond yields collapsed during the Covid lockdowns and remains sensitive to falling yields.

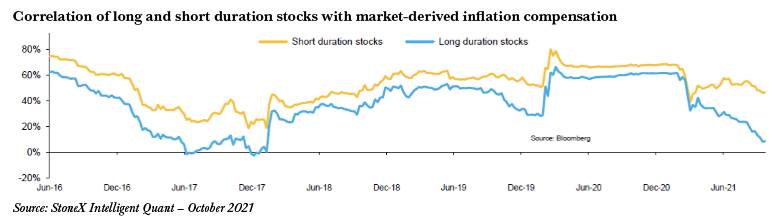

However, in recent months, there has been a subtle shift in market behaviour: the positive correlation of short duration stocks with inflation compensation rates has remained intact, while the correlation of long duration stocks has tumbled to almost zero. It seems that long duration assets are vulnerable to inflationary persistence even in a world of unusually low interest rates.

For now, duration is hanging in there, hoping that inflation will be transitory, leaning on monopoly power to uphold pricing power, hoping that investors will still ‘want a piece of the future’ (think Tesla, again) and have forgotten about the option value of cash.

Since 2009, the duration of US investment-grade corporate bonds has risen from six years to almost nine years; the estimated duration of the S&P 500 equity market index has jumped from 20 years to 55 years, bettered only during the millennial tech bubble.

The pull towards long duration assets is drawn from a fantasy world in which interest rates can never rise. The reason that they can never rise is that the pain of capital destruction would be swift and terrible. Sandy Nairn’s new book, The End of the Everything Bubble, concludes that “every plausible scenario involves significant disappointment, not just for stock market investors, but owners of other asset classes too”.

The storming performance of corporate earnings has appeared to vindicate the long-equity, pro-growth, short-volatility portfolio, but earnings momentum is waning as cost inflation bites into margins. It may yet be a while before policymakers raise interest rates, but it is high time to stop investing for the duration.