This article was originally published in November 2020.

Many farming and food companies are investing or plan to invest in improving the sustainability of food production. This Craigmore commentary, the first in a three-part mini-series, examines the strategies of food companies and farmers to improve their environmental footprints. While sustainability is a much broader topic, this series focuses only on strategies to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and climate change mitigation.

This first part in the series looks at the commitments to reduce net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions recently made by companies ranging from Tyson Foods (US) to Tesco (UK) and the movements made by farming industry leaders.

Greenhouse gases and farming

Non-CO2 emissions (methane and nitrous oxide) from agriculture (the production of food and fibre) are estimated to account for approximately 4.8–7.6 gigatonnes of CO2 equivalent greenhouse gases per annum (IPCC/FAO figure). This accounts for between 9% and 14% of humankind’s total GHG footprint (see IPCC report).

As a result, farmers, food companies and governments are rapidly establishing strategies to reduce the greenhouse gas emissions intensity of farming (and food) systems. Emissions intensity is the amount of greenhouse gases per weight, volume, calorie of food, nutrient or protein produced.

In June 2020 the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change launched the Race to Net Zero campaign to support the global Climate Ambition Alliance to achieve net zero emissions by 2050. Impressively, Danone has committed to migrate all the food it brings to market to net zero by 2050 and J. Sainsbury will migrate its operations to net zero (although not necessarily those of its farm suppliers) by 2040. Several food and farming operations, including Fonterra and Craigmore, are working to produce net zero dairy products well before then.

What are food brands and retailers doing?

As well as committing to change their own (Scope 1) operational emissions, many food brands and retailers are also committing to manage their (Scope 3) relations with farm suppliers in such a way that the emissions footprint of these farms is also reduced.

This table summarises some of the larger food companies and retailers’ commitments to reduce their own (Scope 1) or their farming suppliers’ (Scope 3) emissions. The commitments are meaningful.

| Food brand / food retailer | Own operations (Scope 1) + farm suppliers (Scope 3) | % reduction in emissions intensity or net emissions | Target date |

| Danone | Scope 1,3 | 50%, net zero | 2030, 2050 |

| Unilever | Scope 1,3 | 50% | 2030 |

| General Mills | Scope 1,3 | 28% | 2025 |

| Mars | Scope 1,3 | 27%, net zero | 2025, 2050 |

| Tyson Foods | Scope 1,3 | 30% | 2030 |

| Arla | Scope 1,3 | 30% | 2030 |

| Cargill | Scope 1,3 | 30% | 2030 |

| Coca Cola | Scope 1,3 | 25% | 2030 |

| Kellogg | Scope 1,3 | 20% | 2030 |

| Tesco | Scope 1,3 | 15% | 2030 |

| Wm. Morrison | Scope 1,3* | Net zero | 2030 |

| Nestle | Scope 1,3 | Net zero | 2050 |

| M&S | Scope 1 | Net zero | 2014 |

| J. Sainsbury | Scope 1 | Net zero | 2040 |

| Fonterra | Scope 1 | 30%, 100% | 2030, 2050 |

Source: Map of Ag research

What are the food brands asking from governments?

As well as making these commitments, some food companies are lobbying governments to increase mechanisms to trade in and price carbon. Olam, Nestle, Danone and Unilever have all weighed in on this. To meet emissions commitments those companies are going to need carbon markets in which to buy units offsetting that part of their target that is unlikely to be achieved with reductions from their own or their growers’ direct operations.

What are farm leaders saying?

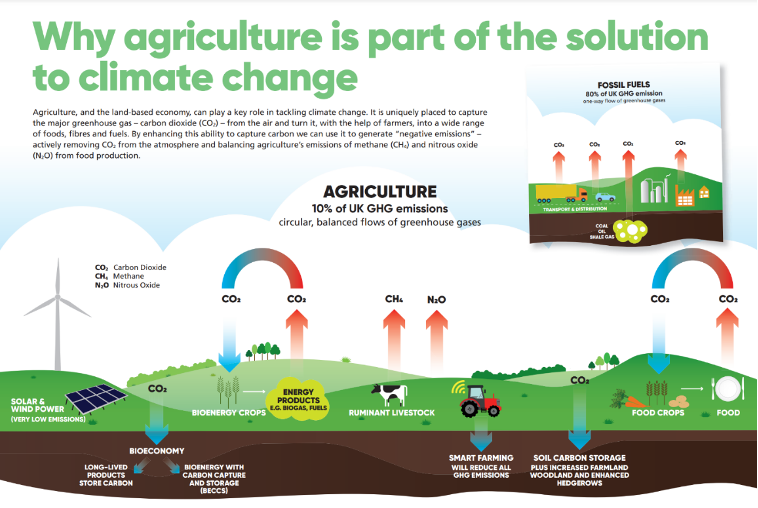

Among farmers themselves, as we noted in earlier Craigmore Commentaries, the National Farmers Union of the UK has a policy of reducing net emissions from UK agriculture to zero by 2040. Its infographic below sets out some of the ways it envisages this happening.

Australian farmers have also set the target of being net zero – in their case by 2030. Notably the red meat sector in Australia, although responsible for 70% of emissions from Australian agriculture, has also backed a 2030 net zero goal. It plans to be the first livestock sector producing carbon-neutral beef.

Meanwhile in New Zealand farmers agreed a plan to reduce greenhouse gas intensities in October 2019. Even though this was a step down from the inclusion of farming in the country’s Emissions Trading Scheme (ETS), for which Jacinda Ardern’s government had hoped, it was still a historic acceptance by Kiwi farmers of the need to change on-farm practices to reduce their carbon footprints. Farmers have agreed that if sufficient progress is not made in reducing emissions, then agriculture may be introduced into the established ETS, which prices and sells carbon offsets (currently at approximately NZ$35 per metric tonne of carbon).

The movement in the industry towards sustainable outcomes is under way. Never have farming and food industry leaders been aligned towards the same sustainability goal. This should result in real sustainability gains in food and farming.

The next two articles in this mini-series will look at specific initiatives under way in the food industry to reduce emissions using Map of Agriculture, a farm data platform set up by Craigmore, and Craigmore’s own farms as case studies.