For income-hungry investors that have hoovered-up corporate debt in recent years, this really matters.

Call me nostalgic, but investment grade (IG) credit just isn’t what it used to be.

Theoretically, IG bonds and borrowers are highly unlikely to default. In practice… well, we all remember those triple-A mortgage backed securities during the credit crunch, don’t we?

Triple-A-rated borrowers perch at the top of the IG credit tree. On the lower branches sit the triple-Bs, which hover just above the riskier ‘high yield’ or ‘junk’ status.

So triple-Bs live on the edge: modest economic changes can reduce their creditworthiness, triggering downgrades to ‘junk’. These are called ‘fallen angels’.

Many investment fund mandates prevent them holding ‘junk’ bonds. This means that ‘fallen angels’ can quickly create forced selling in credit markets.

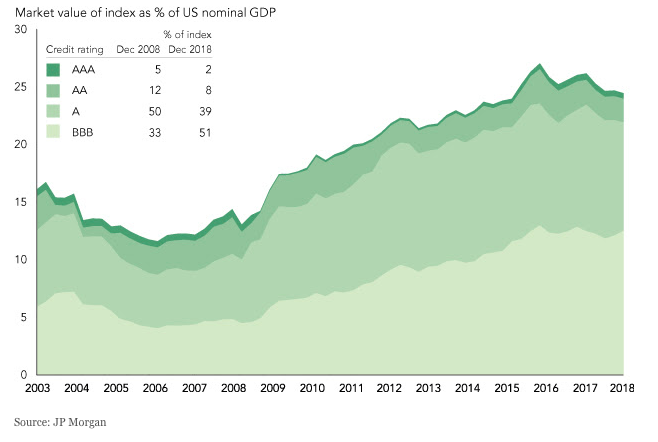

That’s why this month’s chart is critical. It shows that the proportion of triple-B-rated bonds has risen to around half of all IG debt in the US, from only 25% in 2000* and 33% in 2008.

It gets worse. The average quality of IG credit – especially triple-B – has fallen dramatically since the credit crunch: compared to recent years, typical triple-Bs have greater leverage and fewer protective covenants.

The chart also shows how corporate debt has ballooned in size relative to US GDP, as has the amount of corporate debt held in ETFs and mutual funds*. By definition, passive funds buy what’s on offer, regardless of quality. They’re also indiscriminate sellers.

Credit markets have been a ‘go-to’ place for the income-starved in a low-interest rate world. But who will want to take on credit risk when cash offers a safer yield? Or when the cycle turns causing downgrades in credit ratings which force credit funds to sell, even at huge discounts?

With record levels of poor quality triple-B debt on the precipice, credit markets are primed for an historic avalanche, as our CIO Henry Maxey outlines here.

Trigger warnings

We think credit markets will see dynamics similar to a bank run. Once people know there’s a problem, they will all rush for the exit, which will create a bigger problem causing more people to sell, and so on. And when liquidity dries up, investors will sell more liquid securities instead, pushing the crisis into more liquid markets.

The great news is that benign markets are bad at differentiating between good and bad credit. This means that protection against a credit market meltdown is cheap and very powerful. And that’s why Ruffer portfolios own credit market protections.

We wish all our readers a very prosperous New Year.

This article was originally published by Ruffer, who have kindly allowed The Property Chronicle to republish.