The CIO of Odey Asset Management, shares his thoughts on recent events in

the UK economy.

There was a time when markets were in the ascendancy, when they ruled, rather than were ruled. One of the sadnesses for those of us who have been around a long time is that we have watched a great ocean become a lake. We have watched politicians increasingly understand how to minimise the influence of market economics on any policy they might have had. My sense was that the culmination of all of this was when Covid came along and we saw that governments realised they could do anything they liked and markets could not basically fight back.

Once we reached this point, it was but a short step to watching my old graduate Kwasi Kwarteng do his mini-budget in style on that Friday and, by the way, Kwasi learnt absolutely nothing when he was working for us, but that it was very, very wrong that he should be blamed for what happened on that Friday. As we all now know, but had perhaps only an inkling at first, is that what we are in with liability-driven investment (LDI) is the same kind of crisis that you could argue we had with the whole banking crisis of September 2008, when banks’ loan-to-deposit ratios reached 130%.

What is so very bad about this situation is the corruption of the pensions industry. We always believed that part of the City of London’s strength was that you had a huge amount of unleveraged capital which was at the heart of it and that unleveraged capital could not be assailed. Remember in the old days no pension fund could borrow money: they could invest in companies that borrowed money, but they couldn’t borrow money themselves. In the same way, with your personal pension, you cannot buy a hedge fund, because that would be dangerous. What we see with the pension funds is that something that was meant to provide security by matching the duration of liabilities to that of assets – LDI – turned into something very bad.

Once we saw defined contributions coming in and defined benefits going out, suddenly the actuaries were able to come in and start to talk a different language: “Hey, you might have got these assets, but think of what those liabilities could be in 20 years’ time”. As soon as you start looking in those terms, the only way out, and it was a sensible idea, was LDI. All these things start as a good thing and end as a bad thing. In that early period in 2003, the actuaries were saying: “Hey, look, your assets are at 70 and your liabilities are at 100 if you take them through. Why don’t we invest on the basis of the 100 bonds, so that when interest rates, if they come down, won’t have you suffer from liabilities creeping up much faster than your assets can possibly handle.” And that was precisely what happened in 2003.

“We have lost the skill set to understand what leverage and risk basically does”

However, in 2020, when we went into this up-cycle in inflation and this fall in bond yields, with this kind of leverage still in place, it really showed zero understanding of markets. It really drives home why the last 15 years have been potentially very devastating in terms of how significantly we have lost the skill set to understand what leverage and risk basically does, and the fact that markets and cycles can come back and be as ferocious as they are.

David Copperfield has always been my favourite book and part of the reason is because it was obviously Charles Dickens’ autobiography. If you remember the way in which he sets the scene is that you had two groups of people: one, who basically lived by the sea – and they were the people who understood the nature and ferocity of the sea, so they had a profound respect for the ways that nature deals with things and that informed the way they related to each other – and in the other group you had Steerforth and his friends from the city who had lost any of this skill set, any of this understanding of natural forces, so they were kind of sophisticated, impressive, but really with no understanding of the world as it was. It was these two different worlds colliding which basically made David Copperfield such a great book. When Ham and Steerforth are lying dead on the shore outside Lowestoft, David Copperfield declares: “Anything, Steerforth, you could have done anything, reached the stars! Waste, waste. Waste all waste.”

It’s just not enough to be given all these talents. We are going to be refined by the fire and the only people that really earn their spurs are the people who come through – having basically discovered that those talents weren’t enough – and they had to have grit to come through to the other side. Dickens has that great line: “Whether I shall be the hero in my own story or whether someone else shall have to occupy that station, let these following words make true.”

Now, my point about this is actually, in investment terms, you know fund management is not just about being clever or very wise. There was a very good piece, I don’t remember who wrote it, but it showed you that even God would have been sacked about 18 times as a fund manager. My point is not to compare myself with God, but that half of this story is how do you know whether you are on to a good thing and whether it is right?

In my world, you must start with that leverage right at the beginning, not at the end. The story of LDI is that it was a brilliant thing at its inception. Bond yields were at 6% and they fell almost all those six percentage points to virtually zero. They saved the pension fund industry for the first 20 years and now they are going to destroy it, in lots of ways. What you have now is a leveraged pension fund – leveraging into bonds in a cycle in which governments don’t mind spending money that they don’t have. Basically, they will leave it to the market, ultimately, to tell them that they can’t carry on – and that’s not taking as long as maybe the politicians thought it would – but that’s the cycle that we are in.

“The one good thing about inflation is, provided there is always the expectation that interest rates are going to go up, people don’t feel like borrowing”

The truth is that everybody has been hanging around waiting for the pivot from Jay Powell at Jackson Hole. We’ve just had the pivot – the pivot is none other than governments basically saying, “We will do anything we can not to have a recession and we will spend any amount of money”. The best thing that can happen is back to Kurt Richebacher. Poor old Richebacher, what killed him was that debt never stopped rising faster than GNP and, finally, 15 years after Richebacher died we now have nominal debt rising slower than nominal GNP, so there is something going right. If you go back to the 1970s, it was pretty crucial for them that the leverage in the system should come down. The one good thing about inflation is, provided there is always the expectation that interest rates are going to go up, people don’t feel like borrowing. It’s the only time in a fiat currency world in which you can see inflation outperforming borrowings.

In terms of how I see the world, the answer, it seems to me, is that the pension funds are holding about 40% more bonds than they needed to have and the average duration is about 20 years. I would be very surprised if they didn’t suffer losses on that £1.5tr of LDI – and that’s the net amount rather than the gross number, by the way. They are probably owning £400bn pounds worth of bonds that they shouldn’t really be owning at this point in an inflationary cycle of this kind.

That is going to be an ongoing problem, because it seems to me the Government is likely to have to pick up the pieces yet again, another socialisation of bad decision-making.

I think this thing is going to run and run, it’s not going to be over by Friday. Having said that, a lot of the pain of all this has been felt over the past 25 years. In 2003, pension funds, under the illusion that entrants were paying for retirees, could have a growth outlook in their portfolios, so it was no surprise if 70% of their assets were in equities at that point in time and that meant there was a risk culture. Today, you have 30% equities in a pension fund, so it has basically already contracted and you can feel that lack of investment through the system. It means that there are a lot of companies, especially with the UK being so unpopular, that are fantastically cheap at this point.

“Most people want to be bearish and what we are really talking about is real against nominal”

I think, having been one of the early hedge fund pioneers in 1991, what always struck me was how few people, how few hedge funds, got out of the 1970s alive and George Soros was pretty unique in doing that. Most people want to be bearish and, actually, what we are really talking about is real against nomina0l: it is real asset prices that are going to be falling, not nominal asset prices. It’s going to be very difficult for people to differentiate between the two.

This gives rise to a potential idea. In a world in which LDI has forced the pension funds to deleverage: they are just trying to sell whatever they can sell and so indexed-linked bonds are sold off just as fast, if not faster because of their perceived duration risk, than the conventional bonds. As the indexed-linkers come down – and the low was obviously the day before the Bank of England came in – but at that point they carried a 1.92% real yield. If you believe that the world is going to grow faster than 2% for the next 50 years, then put your hand up, but I don’t think that’s what most of us believe.

“When individuals were asked what was the best year they’d ever known, they said 1976”

The reaction of governments to the absence of growth is that, if they can manufacture growth, even if it’s called inflation, it will look good. Remember, when individuals were asked what the best year was they’d ever known, they said 1976, which was the year when wages went up by 20%. People couldn’t believe their luck, but of course inflation went up by 22%. The point is that the index-linked bonds are very interesting here, but remember they are 27% of the UK bond market. In a liquidation crisis, they are going to be sold off by the same people who are selling off everything else. You might have many opportunities to buy these things, but you shouldn’t be frightened by that.

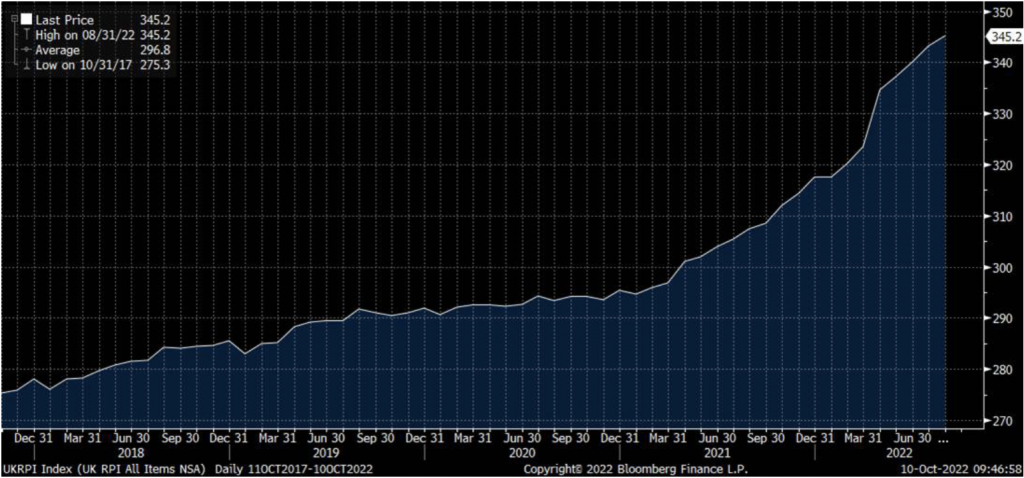

My cry is, just look at the last year, when the increase in the RPI means that you will have received an 11% coupon on your index linked and your index linked is down 88% on that 11% coupon. The answer is, if you are a private individual, remember that index linked is the only way in which you really turn income into capital, because the RPI is added to your redemption yield. It really shouldn’t be treated this way; it derives from the original thinking that gilts are basically an exempt asset class. Conventional gilts are issued at 100 and they are redeemed at 100 and who cares what they trade at in between times? But linkers are a different game, because you could issue it at 100 and you might be redeeming it at 1,200 and that 1,200 turns out to be an exempt capital gain. For how long does that last? I think the Government has got a lot of more pressing questions that it needs to answer before it gets to that one.

My title was ‘Unmooring expectations’ and my point with where we are today is we still live in a world in which, if you look at the Bloomberg forecast for the UK for next year, the RPI forecast is 3.3%. I don’t think we really hit the bottom in any of this until, when someone asks somebody else what is inflation going to be next year, they say I haven’t got a clue, and that will be the moment when we are truly back in business.

This is an edited version of the remarks made by Crispin Odey, CIO of Odey Asset Management, at a reception held recently to mark the 20th anniversary of Halkin Services, a risk analysis and asset allocation service.