The disruption and uncertainty permeating Australia’s economy as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic will mark the local housing market for some time to come. Demand in the market is always a challenge to predict and even more so given the rapid change in the factors that traditionally influence the market in recent months.

During the early stages of the pandemic, economic recovery was widely predicted to be shaped either as a U or, by a few optimists, a V. Given we now have a better understanding of the virus’ behaviour and impact, the recovery is likely to be shaped more as a sawtooth, a period of bumpiness followed by a gentle uptick.

These bumps aren’t expected to be enough to derail the gradual upward trajectory but will present challenges in particular geographies or sectors of the economy. In Australia, we’ve seen the pandemic result in a firm close on international borders, significant domestic border restrictions and wide-spread social distancing policies. Currently, the Victorian capital city of Melbourne is experiencing a significant second outbreak that has resulted in a full lockdown and curfews.

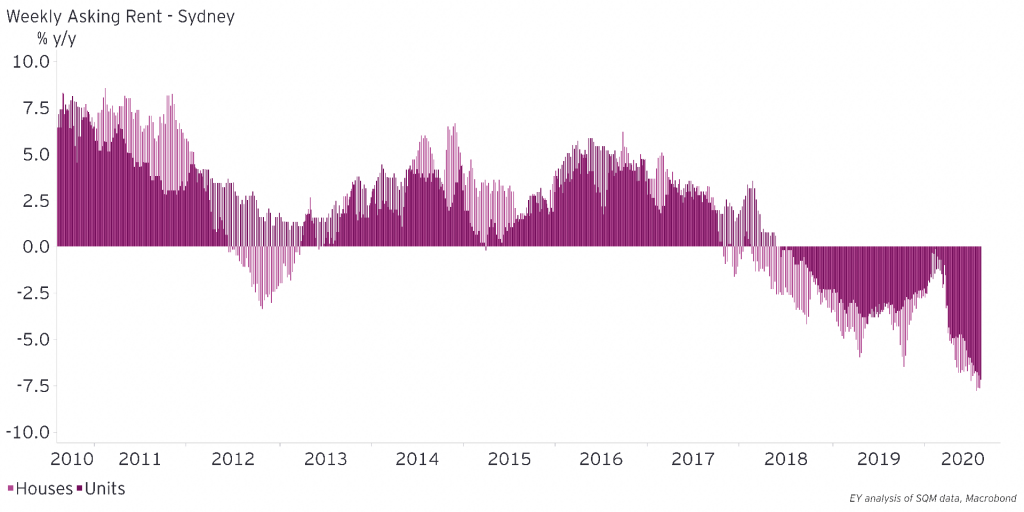

From a housing perspective, the impact of this economic shock is being felt most in the rental market. Rents in Australia’s major capital cities are among the highest in the world compared to average salaries, however if we take Sydney as an example, rents have already fallen back to 2013 levels. Not only are advertised rents falling, but the stock of rent paid – as measured by the Consumer Price Index – fell by 1.3 per cent in the June quarter, the largest fall since the series started in 1972. In part this reflects rent deferrals, which according to The Reserve Bank of Australia have been successfully negotiated by around 5 per cent of tenants since the end of March. More broadly, lower demand from foreign students and immigrants, a weakening labour market alongside an increase in supply as short-term holiday rentals pivoted to longer term rent have impacted.

Rents are falling amid lower demand and rising supply

In contrast, house prices have performed better than expected with an orderly correction. Since mid-2019 prices have been rising but have dropped 1.6 per cent in the three months to July 2020. Despite this, prices are still just over 7 per cent higher than 12 months ago.

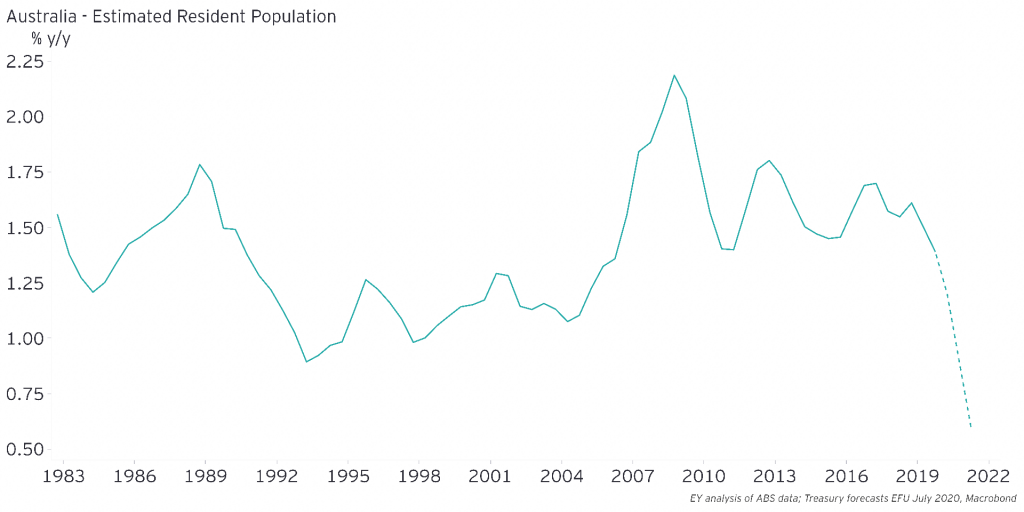

For most countries, population growth is a key foundation of economic activity, and Australia is no exception. With a relatively small population, migration has always been essential to national population growth, making up two-thirds of Australia’s growth, which has been running at around 1.5 per cent per year. But international border closures mean the growth rate will slump to around 0.7 per cent per year, the slowest pace since the First World War. Put simply this translates as less demand for housing, be that for rental or sales.

Australia’s population growth is set to be the slowest in over 100 years

Household formation as a result of this crisis is challenging to predict. Young adults between 20 and 29 years have been disproportionately hit by the economic downturn, with job losses for this age bracket at just over 7 per cent between mid-March and end-July. Those young adults entering the workforce are going to face challenges not seen for decades when it comes to securing jobs[1]. And job insecurity – which has surged to be 22 per cent higher than in 2019 – is a recognised factor in how likely someone is to form a new household.

That suggests young people are more likely to stay in the family home for longer or even move back home. But because house prices have eased, interest rates are low and government stimulus has been enacted, first home buyer enquiries on real.estate.com.au are up 91 per cent from year-ago levels. On that basis, housing formation could go either way as a marker for future demand.

Similarly, changes to buyer preferences is difficult to predict. Whether people bet on rolling lockdowns becoming the norm and therefore look to buy properties more suited to that (bigger backyards, dedicated home office, or small city apartment with a country place to escape to), is open to debate, particularly if that means a smaller financial buffer. As is the question of whether the growing acceptance of remote work will see an exit out of cities in favour of cheaper regional areas with different lifestyle options.

While buyers and sellers of established housing can respond fairly quickly to changing market dynamics, the supply of newly constructed housing is harder to shift as construction already underway doesn’t merely stop in response to potential demand changes.

The pipeline of residential construction, particularly in Melbourne and Sydney where demand had been strong before the COVID-19 hit, will continue to feed into new supply over the year ahead even as demand has dropped away. This is particularly true for apartments, which have long, complex timeframes. There are 189 thousand dwellings currently under construction, almost 70 per cent of which are apartments.

The one certainty we have at the moment is that finding the equilibrium between demand and supply in the housing market is not going to be easy any time soon. Just as we see bumps in the gradual recovery in the economy requiring businesses and households to remain nimble, so we see bumps in the housing market, that will also require nimbleness on behalf of buyers, sellers and developers.

The views expressed in this article are the views of the author, not Ernst & Young. This article provides general information, does not constitute advice and should not be relied on as such. Professional advice should be sought prior to any action being taken in reliance on any of the information. Liability limited by a scheme approved under Professional Standards Legislation.

[1]https://www.ey.com/en_au/public-policy/driver-or-passenger-how-recessions-impact-young-australian-workers