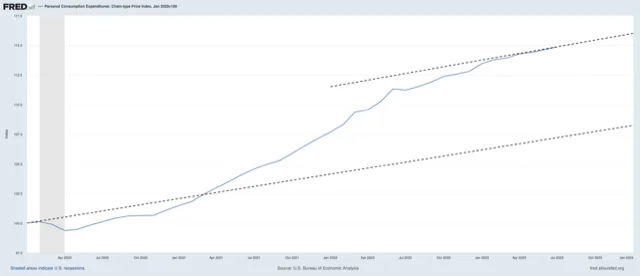

After more than two years of high inflation, the Federal Reserve finally has inflation back on target. The Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index (PCEPI) has grown at a continuously compounding annual rate of 2.1 percent over the last three months, new data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis shows. Bond markets are pricing in roughly 2 percent PCEPI inflation per year over the next five years.

Some—including some Fed officials—are reluctant to accept the good news. And their reluctance is understandable. Annual inflation rates remain high. The PCEPI grew 3.2 percent over the last year. Core PCEPI, which excludes volatile food and energy prices, grew 4.2 percent. However, these high rates largely reflect price increases that occurred months ago. Those distant price increases should not be used to justify further rate hikes today.

An analogy serves to illustrate. Suppose you decelerate from 45 MPH to 20 MPH while approaching a school zone in your car. When you reach the school zone, you look down at your odometer and see that you are going 20 MPH. At that point, you do not stomp on the brake just because you have averaged 35 MPH over the last quarter mile. Of course your average over the last quarter mile is greater than your 20 MPH target: you were decelerating to hit that target. What matters now is not how fast you were going, but how fast you are going.

Likewise, the Fed is aiming for 2 percent inflation. Now, inflation is back around 2 percent. The Fed should not raise rates further just because inflation was higher months ago. What matters now is not how fast prices were rising, but how fast they are rising now.

Of course, the price level remains much higher than it would have been had the Fed hit its 2-percent target over the course of the pandemic. If inflation had averaged 2 percent, they would be 7.7 percentage points lower today. But that, too, is not a good reason for raising rates further.

In general, the Fed should set expectations and then deliver on those expectations. The first-best policy is clear: when a change in nominal spending pushes the price level above (below) the projected path, the Fed should promptly tighten (loosen) policy to bring those prices back in line with expectations. The Fed has not done this. But it does not follow that the Fed should do this now. Since the Fed did not act promptly, the first-best option is off the table. We can only hope for a second-best policy. We must seriously consider what the Fed should do when it hasn’t done what it should have done.

Given that the Fed has made it clear—since at least December 2021—that it would gradually bring the rate of inflation back down to 2 percent but permit the price level to remain elevated, it would be a mistake to change course now and try to bring prices back down to where they would have been had it never erred in the first place. People have adjusted their expectations. As shown below, the TIPS spread—adjusted for the difference between PCEPI inflation and Consumer Price Index Inflation—suggests market participants are pricing in 2.0 percent inflation over the five-year horizon and 2.1 percent inflation over the ten-year horizon.

More importantly, people have renegotiated their wages and purchase orders with those new expectations in mind. To course correct at this late stage would amount to a very painful contraction.

We’ve already borne the costs of an unexpected inflation. There’s no good reason to tack on additional costs from an unexpected deflation.

This article was originally published in AIER and is republished here with permission.