Öslem Tureci and Uğur Şahin – the founders of BionTech, which, together with Pfizer, pioneered one of the first covid-19 vaccines – are remarkable individuals in a wider sense. While their scientific research and business success, leading to a US$3.6bn net worth, are impressive, their most significant impact will likely be on how immigrants are viewed in German society.

As such they also represent two very different immigrant groups and their path within the German educational system. Whereas Tureci, the daughter of a Turkish surgeon who emigrated to Germany, comes from a rather privileged background, Şahin is the quintessential poster child of a Gastarbeiterkind (child of migrant workers) of the sixties, with a father working at the Ford Motor factory in Cologne.

What both had in common, though, was access to a well-developed and free-of-charge educational system, which helped to create a level playing field and advancement opportunities along with social mobility.

So, how does the German educational system compare globally?

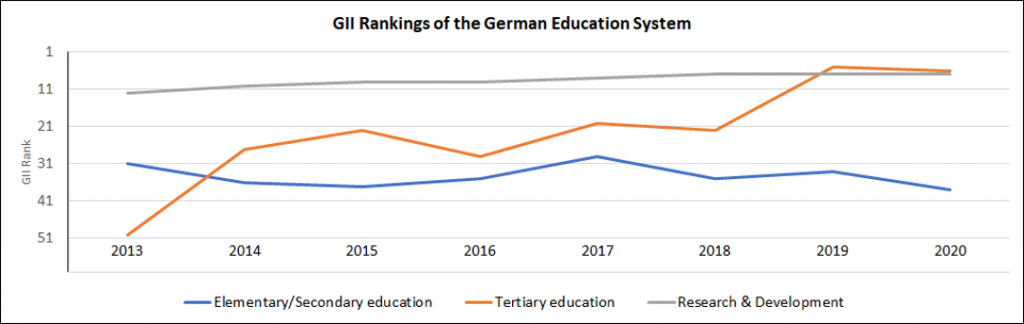

Pretty well, when considering tertiary educational quality and R&D output as outlined in the Global Innovation Index (GII) ranking tables illustrated below.

However, the progress made within advanced education and R&D over the past couple of years is not mirrored in elementary and secondary educational achievement, where the country shows significant gaps and barely ranks in the top 40 (out of 200 countries evaluated).

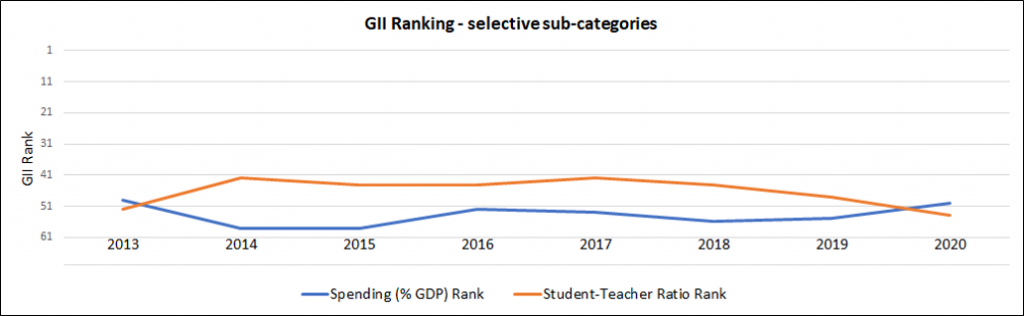

Drilling down into individual sub-categories, significant funding and staffing issues emerge, in particular with respect to funding levels in general as well as the student-teacher ratio, commonly considered to be key quality drivers for an educational system’s success or failure.

How can this disconnect be explained?

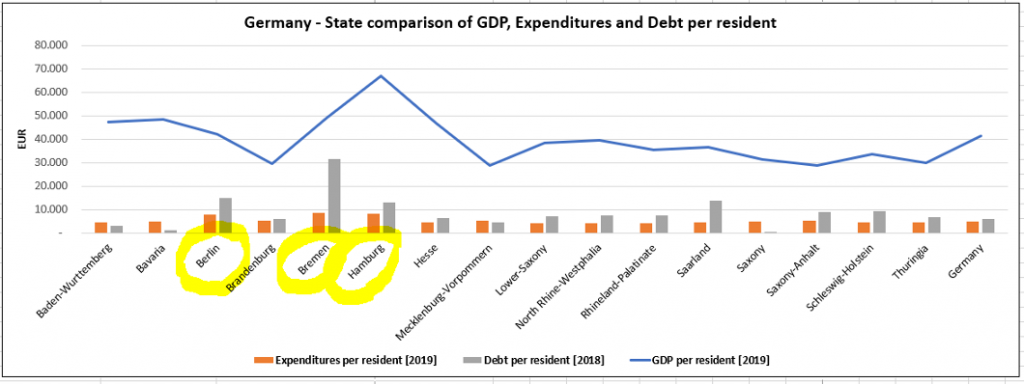

Driven by its post Second World War constitution, Germany’s educational system is fragmented on a Bundesland or state-by-state basis and administered by state-level ministries of education. Apart from partially incompatible curricula, which are a major headache for families moving states within Germany, this also leads to vastly different funding levels of educational systems, in particular schools. Thanks to federal co-funding, this impact is somewhat mitigated for universities.

Due to their comparatively small population, the three city-states of Berlin, Bremen and Hamburg show relatively high expenditures and debt per resident, despite GDP/head ratios on a par with other states.

These already disproportionately high levels of overall costs and indebtedness per resident limit the city-states’ financial flexibility going forward, which includes excess spending on education.

Which other key success drivers come into play?

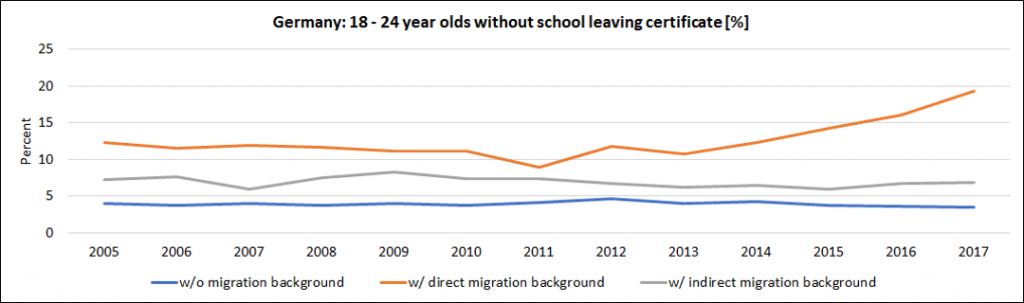

Success in Germany’s educational system is significantly influenced by a student’s background. Apart from general socioeconomic factors such as family income and parents’ educational and professional background, migration impacts are significant – as outlined in the following graph.

The fact that first-generation migrants are three times as likely to leave school without a degree while second-generation kids on average still face an 80% higher risk is simply unacceptable for a knowledge-based economy.

This issue is poised to become worse over the next decade, since the Assembly of Education ministers of German states (Kultusministerkonferenz) expects roughly 1 million (10%) more students in German schools by 2030 compared with 2019.

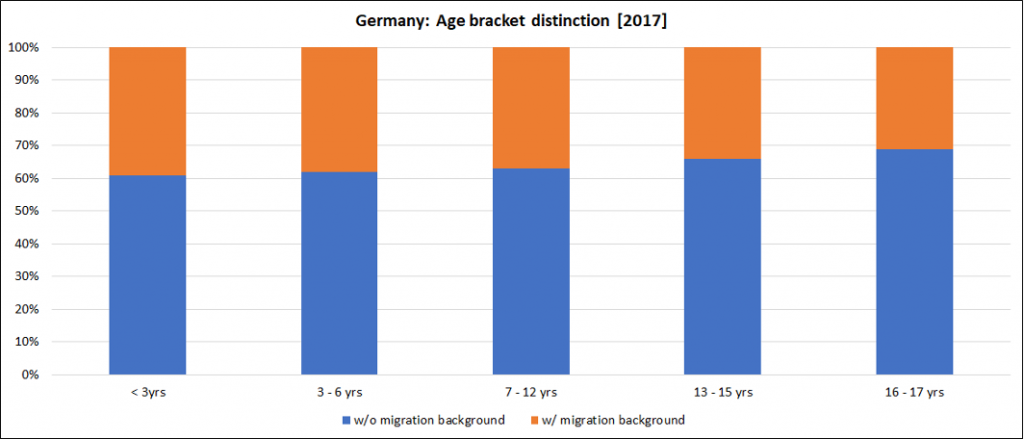

A large portion of this increase (around 800,000 students) will be concentrated in the three city-states of Berlin, Hamburg and Bremen – which, at 19.2%, 16.5% and 18.7% respectively, have a disproportionate share of residents with a migrant background. Looking at the composition of age brackets of current and future students across Germany as of 2017, the challenges for the German educational system going forward become even more obvious.

Four out of ten students in the German educational system ten years from now will have a direct or indirect migration experience. In addition to a larger and more diverse student body, the school system will also need to become much more attractive as a career opportunity for the best and brightest to become teachers. This is even more important as one-third of today’s teachers are going to retire during the next ten years.

Given relatively long lead times, Germany urgently needs to rethink its educational system in terms of structure, funding and quality. This includes providing federal support to German’s city-states as well as some inner-city areas, for instance in North-Rhine Westfalia, which bear a disproportionate share of future challenges.

Looking at the emerging fallout from almost a year of intermittent home-schooling, indicating a disastrous digital unpreparedness of the German schooling system, the matter is even more urgent.

Considering the mixed track record in educating migrants, this demographic trend will require a much more targeted approach to enhance the effectiveness of today’s educational system in order to create a level playing field and for the country to remain a viable player in an increasingly competitive global economy.

The success story of Öslem Tureci and Uğur Şahin shows that in addition to ‘being the right thing to do’, such an approach can be rewarding for everybody.