Cities are central to property performance and the largest cities are seen as hugely important by investors. But the pandemic has turned many received ideas about real estate on their head and we think that performance in these large gateway markets will remain relatively weak after Covid-19.

Real estate is heavily clustered within city economies, but it is not always easy to identify why some locations do better than others. Over the past decade or so, many investors felt they had found an answer in targeting the so-called gateway markets.

Gateways are large, well-connected urban hubs and include both global centres, like London, New York and Paris, and smaller, but still significant, regionally orientated markets, such as the other big US cities and several European capitals.

In our analysis of European and US markets, we considered 12 gateway cities in depth: the global markets of New York, London and Paris, and regional centres in Boston; Chicago; Los Angeles; San Francisco and Washington, DC; Amsterdam; Munich; Milan and Madrid.

Pinpointing the defining characteristics of these cities is more art than science, but there are some clear themes. They are generally seen as attractive by virtue of their scale. They have large and dynamic economies, and hold big populations, as well as topping the rankings for levels of real estate investment. They are also regarded as less risky, and this is reflected in the persistently lower yields seen in these locations.

“The first half of the past decade, for instance, saw battered investors retreat into core markets”

But claims that gateways have consistently performed better are hard to justify. The evidence is more persuasive if we look at capital growth in the early 2000s or the immediate post-GFC period, when gateways had a clear lead. But this is likely to have reflected the circumstances of the time. The first half of the past decade, for instance, saw battered investors retreat into core markets, as pricing was highly favourable and there was a heavy aversion to risks elsewhere. Gateway economies also rebounded unexpectedly fast in the early 2010s, generally outpacing national recoveries and those in second tier markets.

In addition, when gateway properties outperformed in the past, this was usually because of rapid yield compression, with differences in income growth much less marked. As such, there is a suggestion that growth has been effectively sentiment driven and vulnerable to a rapid reversal in the abrupt downturns that come at the end of any property cycle. For these reasons, we are not convinced that there is anything fundamental about gateway cities that would underpin elevated expectations for the future.

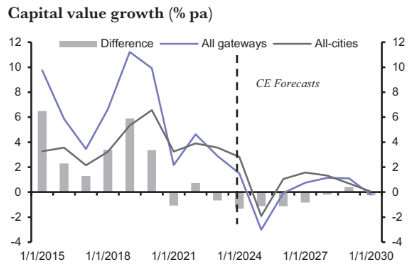

Indeed, since 2016, gateways have lost ground when compared against other global cities, as the post-GFC recovery broadened and pricing in the larger markets looked ever less attractive (see chart). The largest cities underperformed during the virus upheaval of 2020 too, with London and New York particularly hard hit and only a handful of eurozone core markets showing any evidence of capital value growth. Admittedly, the capital falls last year were mild compared to the GFC, but still the larger markets were worst hit.

Not only this, but after Covid there are additional factors that may be stacked against these big markets. Most important will be the influence of increased remote working. Gateways tend to have higher shares of vulnerable office property and, while it is possible to argue that major city CBDs may perform better, this is not a given. Retail concentrations are less of an issue in the largest cities, but much of the evidence suggests that shops in these locations have been hardest hit in the pandemic and will continue to see weaker footfall, even after office workers return.

“Cities already have a significant advantage in amenity, infrastructure and cultural attractions, which will help draw new people in to offset a declining daytime worker population”

Admittedly, demand for other uses may be more resilient in gateways than elsewhere. These cities already have a significant advantage in amenity, infrastructure and cultural attractions, which will help draw new people into offset a declining daytime worker population. This will eventually support leisure, hotel and retail demand and in turn retain city residents. But it may take time for these benefits to show through and we think over the next five years structural change will have a net negative impact.

On top of this, the sort of cyclical yield compression that bolstered gateway performance in the early 2010s is not likely to be repeated. After the pandemic, property yields are still historically very low. And with bond rates also edging higher over the next few years, this significantly raises the floor for property yields. As rental growth is forecast to be underwhelming, given the travails of office and retail sectors, a return to the rates of capital growth seen after the GFC looks unlikely.

Our all-property forecasts highlight a very subdued out-turn (see chart again). Not surprisingly, we expect as lower revival in these larger cities than in other global property markets, with US gateways particularly sluggish as remote working effects are more negative there. Following mediocre out turns from 2016-20, these predictions would imply the weakest sustained gateway performance since records began in 2000. Over the previous 20 years, several gateway markets recorded very strong investment performance, most notably San Francisco and London. In future, the rankings are very different. Of the individual markets, Paris stands out over the next five years, given a consistently strong showing for all commercial sectors.

By contrast, the other global gateways, London and New York, struggle to emerge from Covid-19. Other underperformers include Milan and Boston, reflecting a sector mix that is dominated by office property. Against this, Amsterdam, Munich, Washington DC and Los Angeles rank highest among regional gateways, though even then capital value growth is only in line with the global all-city average.

Despite this, we still think that talk about the death of cities is likely to prove premature. Indeed, in our forecast, the gap between gateways and other cities is not especially wide (at less than 0.5% pts a year) and we expect it to close by the end of the period. By then, some of the effects of structural change will have played out and the strengths of these major markets are expected to be more clearly reasserted.