Rents are known to be volatile as demand and supply interact to create cycles. Rents are also known to vary enormously across properties based on their planning use class, location and condition. This article explores whether the rent setting context is also significant in determining the level of rent and whether this varies in weak versus strong market conditions?

Rent-setting context

There are three contexts to the setting of a new rent: a new letting, rent review and a lease renewal.

The rent for a new letting is determined by the outcome of negotiations between landlord and multiple possible tenants. The tenant will weigh up the benefits and costs of taking occupation. If the market is strong, the landlord will weigh up alternative offers for the unit, or if the market is weak, will dwell more on the opportunity cost of a longer vacancy period.

The negotiation will be conducted between the two parties with neither fully aware of the other’s position or options: how much does the potential occupier want the building and how much competition is there for the space?

At an open market rent review, the rent is not determined by negotiations for the unit in question, but by reference to the outcome of recent negotiating for similar space by unconnected parties.

At lease renewal, the occupier is in place and the focus of negotiations is the new rent and the new lease term. The occupier will weigh up the benefits and costs of moving to alternative space. The landlord will weigh up the potential costs incurred in re-letting and the likelihood of finding a new occupier. The two parties will know more about each other, including the previous rent, although this should in theory have no bearing on the new rent.

This article compares rent changes across the three differing rent-setting mechanisms to see if new information about how rents behave can be uncovered. The results will have implications for modelling and valuing cash flows by investors and lenders, and will also have implications for evaluating leasing strategies.

Dataset

The dataset we have used in this paper is sourced from the RES Lease Consortium. This study collected snapshots of rents and lease details from valuation records of around 50 contributing funds. The contributors were a mixture of life insurance funds, pension funds, specialist funds and unitised funds.

The dataset in 2018 covered a rent roll of over £600m in more than 5,000 units, with 80% of the rent roll and 94% of the units in either retail, office or industrial units.

Any rent changes in the dataset occurring for individual units were allocated to events in the lease.

Where units have been let in different configurations, records have been spliced/split. For example, unit 1 and unit 2 may have been let together and then subsequently let as separate units. This is to stop distortions from major changes to units affecting the results.

Reasonable care has been made to exclude redevelopments, but minor refurbishment between leases, especially for offices, are maintained in the sample.

Very short leases of less than one year have been excluded. These leases often include temporary lets over the Christmas period and subsidised lets (possibly associated with rate saving).

Net-effective rental value

An issue with the rents recorded for new lettings or lease renewals is that there may be associated lease incentives underpinning the letting, the nature of which will vary from letting to letting. The economic impact of these incentives can be quantified in the form of a net-effective rent. This allows different types of rent event to be compared more easily: for example, a change from a rent review to a new letting where the former event will not include incentives, but the latter could feature a rent-free period.

All recorded rents were converted to net-effective rents using a simple reduction in the headline rent proportionate to the length of the rent-free period within the overall term of the lease (to the earlier of break or lease expiry date).

Some data was missing from the study. Data on break incentives and penalties was so patchy that any data that was available has been ignored in these calculations. Capital incentives were also not available, so the effective rent change series may underestimate rent volatility.

It is possible that the negotiated rent is not independent of the other lease terms. For example, a landlord may accept a lower rent in exchange for a longer lease term or the inclusion of a break penalty. While there is strong theoretical justification for this, we have not adjusted our rents beyond allowing for incentives, as empirical literature has found only limited evidence of such lease pricing in practice.

Statistics

Some 6,081 rent change pairs were identified from the RES dataset. The mean length of time between rent events was 4.77 years, while the median length was five years.

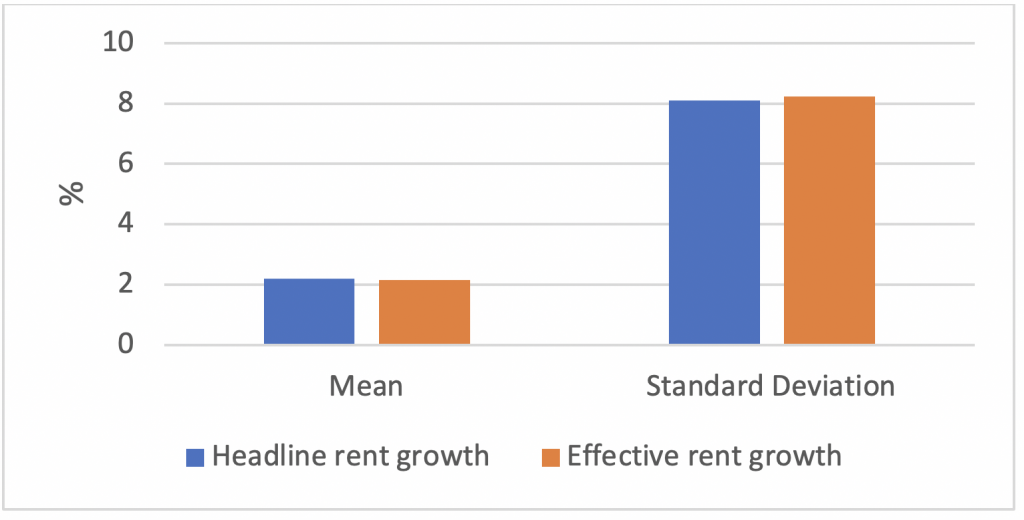

The mean annualised rent change and standard deviation of rent changes was similar on a headline and (after adjusting for incentives) an effective rent basis: 2.2% / 8.1% compared with 2.1% / 8.2%.

Figure 1: Mean and standard deviation of rent pairs, 2000-18

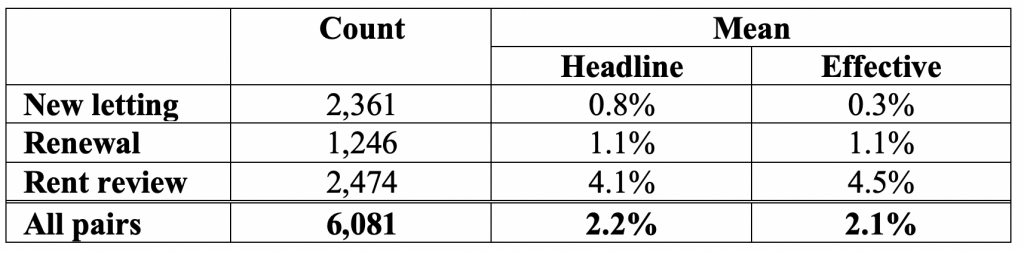

The natures of the second rent event were split 41% rent reviews, 20% lease renewals and 39% new lettings, with the mean rent change for each subsample shown in the table below.

Figure 2: Mean rent change by second event type, 2000-18

Rent change at rent review

Due to the upward-only nature of the vast majority of UK rent reviews, the distribution of rent change at a rent review event is truncated at zero. In other words, only uplifts are recorded, while theoretical downward adjustments are not observed.

Growth in effective rents at rent review is higher than for headline rents, 4.5% versus 4.1%, as the rent on the first event in some instances will have been adjusted downwards if a rent-free period was granted at letting.

New lettings versus renewals

As discussed above, there is an expectation that the characteristics of rent change at lease renewal will differ from that at new letting as the negotiation position between landlord and tenant will differ. For example, tenants with a high cost of moving may be at a strategic disadvantage in a negotiation and settle at a higher rent at lease renewal. Further, in a downswing, landlords will experience a probable vacancy period if the tenant vacates and may therefore be forced to agree a lower rent to retain an existing tenant.

These effects are reflected in the data, with higher growth in effective rents on renewals than new lettings. This suggests that a lease renewal is a more beneficial outcome to an investor, even without taking void costs and vacancy periods into account.

The pattern was repeated in all sectors with the exception of retail warehouses and South East (non-central London) offices. On a weighted basis, new letting rents were also more positive on central London offices. There are two possible further factors affecting the results. Firstly, the re-lettings may have occurred after a vacancy period and market rents may have risen during this time. Secondly, larger offices may have been more likely to have been refurbished.

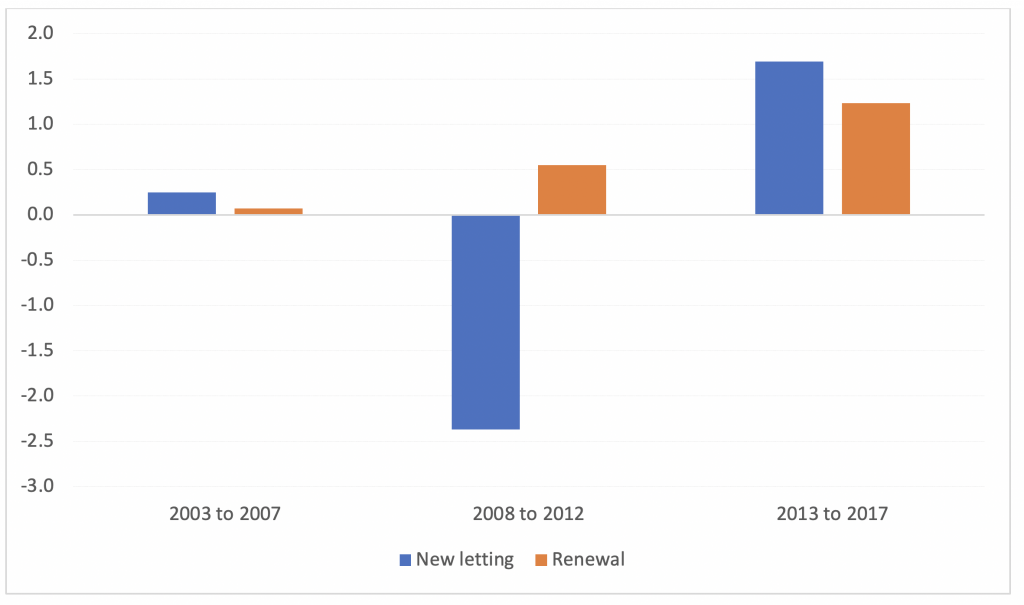

Splitting the sample into strong and weak market states further reveals that the lower effective rent growth on new lettings versus renewals was most pronounced in the downswing from 2008 to 2012, (-2.4% versus -0.4% pa). In the stronger market conditions from 2003 to 2007 and from 2013 to 2017 the rent growth outcomes at new lettings were stronger than those of renewals on a weighted, although not on an unweighted basis.

Figure 3: Mean rent change, weighted basis

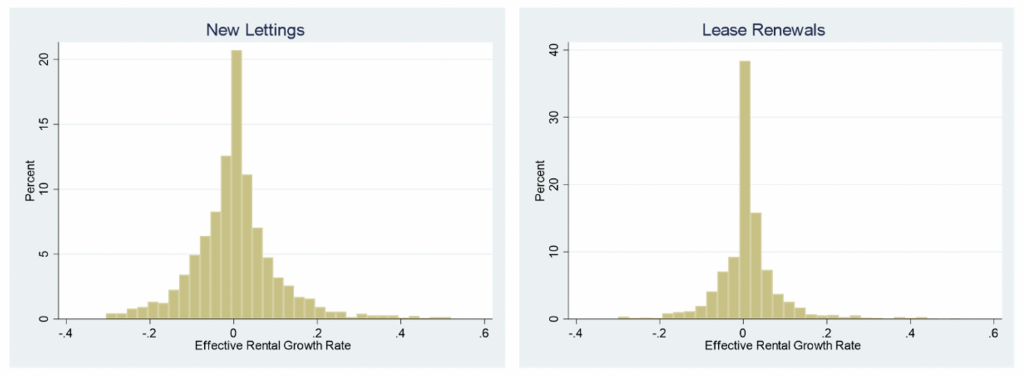

Anchoring also seems to be a feature of lease renewals, with the standard deviation of rent changes higher on new lettings, 10.5% versus 7.8%. This anchoring occurs as both parties are aware of the previous passing rent and the rent agreed tends to cluster more closely around this figure than for a new letting.

Figure 4: Distribution of rent change at new letting versus renewal

Cause of a new letting

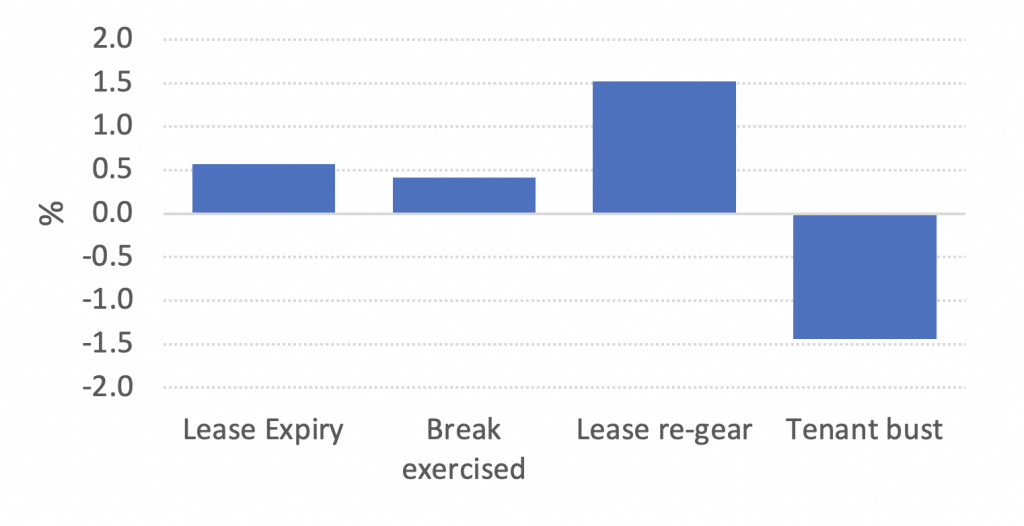

The reason for a new letting is also found to have a bearing on the new rent.

The new rent on a unit where the previous lease had ended due to tenant insolvency had the lowest uplift in effective rents, at -1.4% pa. This reflects the correlation between tenant insolvency and economic conditions, and is possibly also due to a disruptive handover of the unit before re-letting.

Only a very small difference is observed between where the previous lease ended at lease expiry or where it ended at a break option. Evidence from the MSCI Lease Events Review is that tenant propensity to renew and exercise a break are only weakly correlated with a change in rental market conditions.

The most positive rent change is for lease re-gears. This suggests either:

- That a lease re-gear is more likely in strong occupier market conditions;

- that landlords are more likely to seek a lease re-gear when they can raise the rent; or

- that the dataset excludes capital incentives paid to tenants to re-gear their lease.

Figure 5: Mean rent change at new letting by cause of vacancy

Summary

Lease events can cut both ways. In a strong market, a lease expiry is an opportunity to increase the rent – a valuable option. In a weak market, income security and tenant retention are paramount.

Using actual rents achieved on real leases, negotiated between real occupiers and asset managers through two cycles, the results document the average net effective rent changes as a result of lease renewals versus re-lettings.

The evidence suggests that in a downswing, tenant retention leads to a higher average rent than a new letting. The actual cash flow impact would be amplified by a vacancy period and the additional costs associated with a non-renewal. In an upswing, there is no distinction between the rent change at renewal versus a re-letting.

The lowest rent outcome was associated with a tenant default, amplifying the impact of covenant strength on the expected cash flow.

The results can be used to adjust the quantification of the importance of not just the lease term to future cash flow, but also of the tenant propensity to renew and covenant strength.

The question is then: what determines tenant propensity to renew?