On 12 October 1864, Chief Justice Roger Taney, author of the Dred Scott decision, passed away. Abraham Lincoln (finally!) had the opportunity to replace that man. There was never a doubt that Lincoln would nominate a successor. On the other hand, there was no purpose in immediately naming a successor. The Senate was in recess and would not reconvene until after the election.

Following the famous Lincoln-Douglas debates of 1858, there was some curiosity about Lincoln. Those debates concerned the future of slavery in this country. Senator Stephen Douglas, a Democrat, advanced the doctrine of “popular sovereignty”: that whatever the people of a territory might choose should decide the matter. Lincoln’s position was that the federal government could decide the matter of slavery in the territories; and should do so in order to prevent the spread of slavery. But this position was nuanced. It was only implicitly, it was only indirectly, it was only inevitably an attack on slavery.

As Lincoln put it, a house divided against itself cannot stand. Inevitably, the country would be either free or slave. Indirectly, by preventing the spread of slavery to the territories, the Senate as well as the House would tilt against slavery and doom that “peculiar institution.” Implicitly, slave owners, seeing that theirs was a “lost cause,” would seek a deal to preserve their financial interest in slavery in the ending of slavery, as through compensated emancipation.

The Supreme Court said that persons brought

here as slaves from Africa and their children

could never be citizens of this country

Lincoln, in a sense, lost the Lincoln-Douglas debates. The Democrats won that election and, furthermore, were on the march. In Kansas Territory, they used violence and a rigged election to gain approval of a state constitution, which would have made it a slave state were it admitted to statehood by the Congress under that constitution. In the Fugitive Slave Act, they sent manhunters up north to seize persons of colour they described as runaway slaves. And, in the Dred Scott decision, the Supreme Court said that persons brought here as slaves from Africa and their children could never be citizens of this country. That those people were excluded from the self-evident truths expressed in the Declaration of Independence, that all men are created equal and endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights.

The Dred Scott decision was not only radical, it was a despicable lie about the history of our country. It overturned hundreds of similar freedom cases whereby persons who innocently set foot on free soil became – as Dred Scott argued that he had become – a free man. It meant that any descendant of an African slave, no matter how small the percentage of blood, was subject to being seized and reduced to property, they and their children. The truth is, none of us can be absolutely sure of our bloodline. So that, by threatening the freedom of all, the Dred Scott decision doomed slavery.

In 1860, the still new Republican Party looked for a champion. Among the candidates were William Seward of New York and Salmon P. Chase of Ohio, both ardent opponents of slavery and advocates, furthermore, of equal rights. But not all of the free states were ready for equal rights, and the Republicans had to win all or almost all of the free states because they had no chance of winning a slave state. It has always been a funny thing how the Electoral College works. This fellow from Illinois, a free state but not an equal rights state, seemed to fit the bill. While opposing the extension of slavery to the territories, Lincoln had managed, using humour and innuendo, to avoid the issue of equality.

While opposing the extension of slavery to the territories, Lincoln had managed, using humour and innuendo, to avoid the issue of equality

Early in 1860, Lincoln was given an opportunity to deliver a speech in New York City. At the time, speeches were a kind of entertainment. Sponsors would secure speakers, rent a hall, and sell tickets. There was, after all, no C-SPAN or YouTube. Lincoln was originally to speak at Plymouth Congregational Church of the Rev. Henry Ward Beecher (you may have heard of his sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin). But, because of a scheduling conflict, Lincoln gave his speech at Cooper Union.

In his Cooper Union speech, Lincoln identified the positions of the Founders on the matter of the control of slavery in the territories, but also on the overarching issue of slavery. Superficially, this speech was a continuation of the Lincoln-Douglas debates; but, in reality, it was a continuation of the dissenting opinion in the Dred Scott decision. Significantly, Lincoln called for an overturning of the Dred Scott decision, if necessary through the eventual replacement of the members of the Supreme Court.

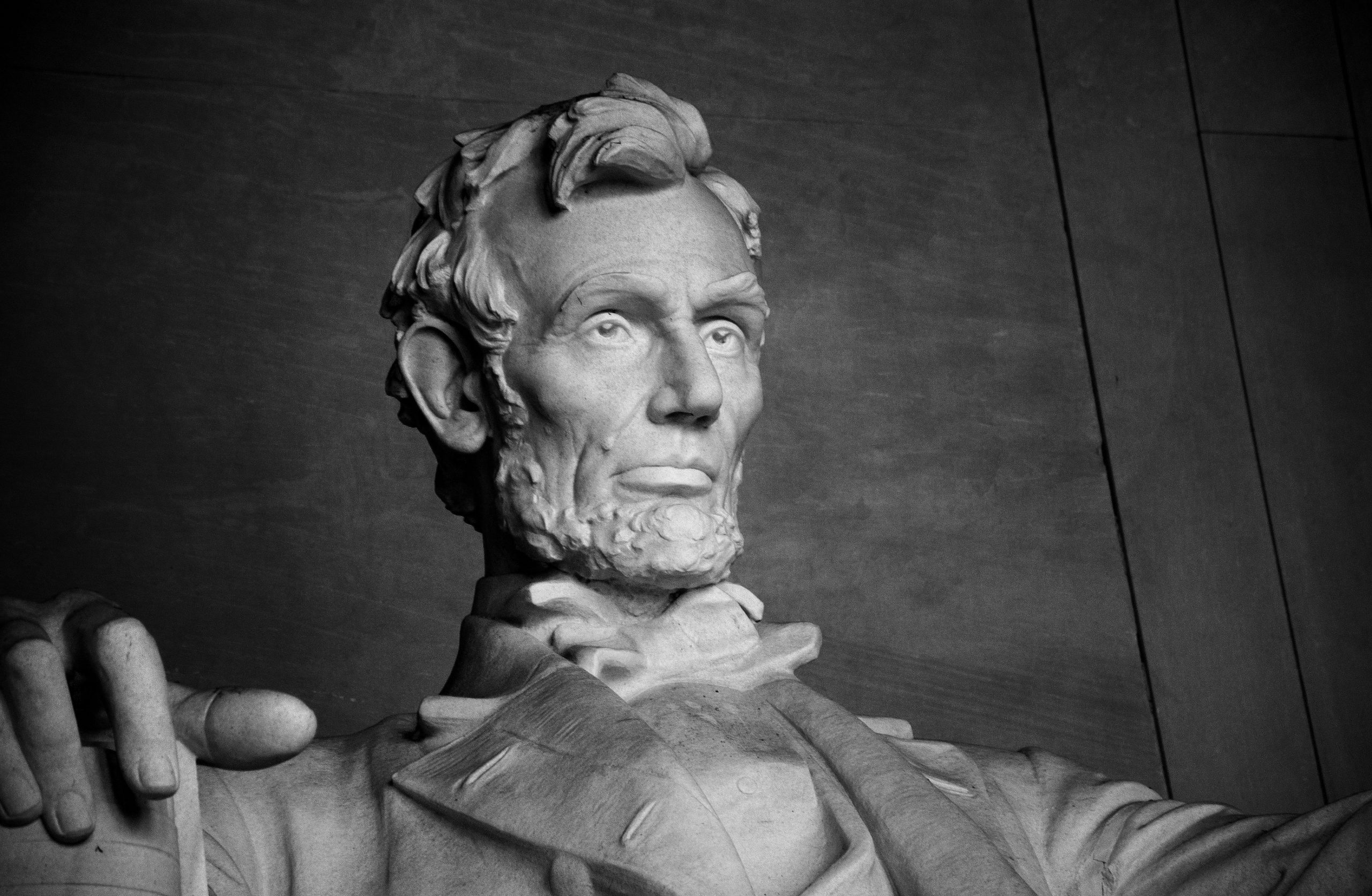

Approximately one year later, Lincoln took the oath of office as president of the United States. As chief justice, Roger Taney administered the oath. He was already old and sickly. Nevertheless, he almost outlasted Lincoln’s first term. Immediately upon Taney’s death, there was speculation as to his replacement. Lincoln held his cards close to the vest, to great political advantage. His one-time rivals representing the different regions of the country and viewpoints within the party, curried Lincoln’s favour. Salmon P. Chase, the greatest civil rights lawyer of that day, in particular, campaigned for Lincoln’s re-election. Then, on the day the Senate reconvened, Lincoln sent over a one-sentence message nominating Chase, who was then confirmed without debate, on a voice vote.

This article was originally published by the American Institute for Economic Research.