On 10 March 2023, Silicon Valley Bank failed, triggering fears of a new financial crisis. Over the next three weeks, US bank share prices fell by 14% and regional banks fared even worse, at 33%. In short order, Signature Bank and First Republic failed and Credit Suisse had to be rescued by UBS.

It has been quiet since then. So, has the crisis passed?

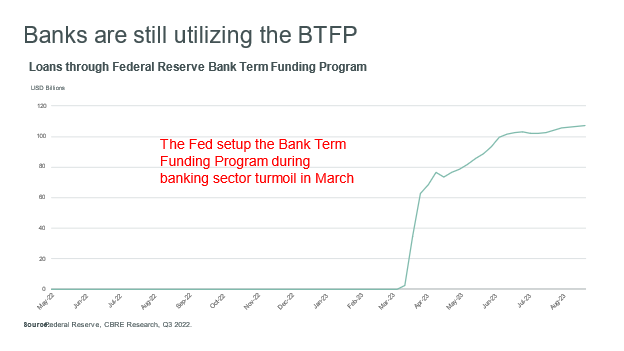

We never believed that a reprise of the GFC was imminent. But that does not mean the problems for banks and investors are over. While real estate did not cause the recent bank failures, the fact that the banks hold $1.7 trillion of real estate loans – and real estate values are down some 24% on average from peak levels – suggests turbulence ahead even if the market is stable right now.

Chart 1

There are several reasons why the current situation is different from the GFC:

- First, the biggest driver of the GFC was the $41 trillion single-family home market. Chart 1 shows how single-family homes have not slumped nearly as much as they did during the GFC. By contrast, the commercial real estate market – the focus of today’s value losses – is an $11 trillion asset class; barely one-quarter the size of the single-family homes market. However, banks face losses on their Treasury bond investments, a risk that was not present in the GFC. It was the “book” losses on Treasury bonds that undermined confidence in Silicon Valley Bank and triggered the run on its deposits.

- Second, banks are better capitalized now than they were prior to the GFC. Tier 1 capital is 8.6% of total assets for community banks, up from 6.7% in the GFC, and 10.8% for regional and national banks versus 9.6% in the GFC.

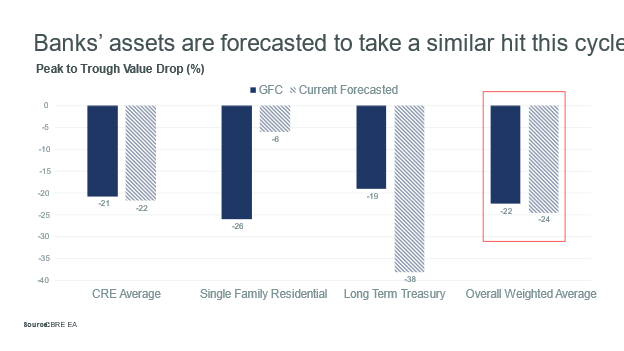

- Third, the Fed has provided almost limitless liquidity to the banking sector. Importantly, the Fed has accepted Treasuries held by banks as collateral at par value, not today’s much lower market value.

Vast amounts of economic and corporate data are highly accessible in the United States. We have downloaded the balance sheets of approximately 4,800 banks, and examined their exposure to real estate, liquid capital, and so on. Using our model to predict likely losses, we expect about 250 banks to fail, representing about 1.5% of total bank assets. While large, these losses are dwarfed by both the GFC (nearly 470 bank failures representing 2.8% of assets) and especially the 1990’s Savings & Loan Crisis (more than 1600 bank failures and 9% of assets).

Chart 2

The problem is that capital market events, such as bank failures, often trigger feedback loops that can be unpredictable. Central banks responded to the GFC by cutting interest rates to zero. Their capacity to follow this playbook, if needed, is hampered by the resilience of the US economy, which is showing signs of reacceleration that could prompt the Fed to further raise, rather than cut, interest rates.

For the time being, the market is quiet. There is no deposit flight, and community and regional banks are working through their real estate losses and shedding non-performing loans. The share price of large banks has recovered, but the community banks are still heavily discounted (Chart 2). However, signs of stress remain. Banks are using the Fed’s discount window at the highest level since the GFC, although they are borrowing only 12% of what they did back then. But usage of the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) (Chart 3) is also creeping up and is now at 30% of the level during the GFC. We are monitoring this carefully, particularly with the Fed considering further rate increases if the economy does not cool. With respect to banking stability, it only seems quiet on the Western Front!

Chart 3