Balance sheets show the trade-off between resilience and optimisation

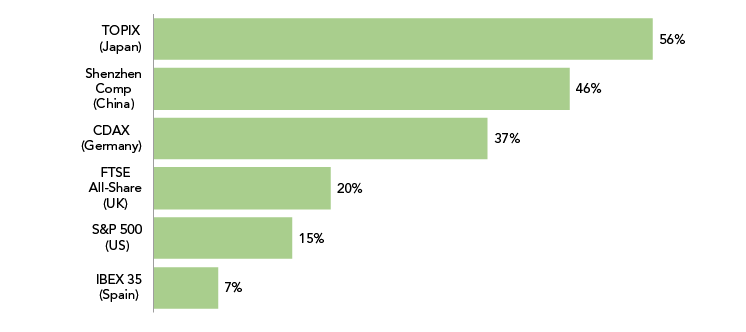

% of companies with net cash

Source: CLSA, Factset as at 21 April 2020

As we highlighted last month, coronavirus is especially dangerous for patients with pre-existing conditions. This is true as much in the corporate world as it is for human beings. The unprecedented and unorthodox nature of the shock should not be allowed to disguise the fact it has revealed a shocking level of fragility amongst public and private companies across the globe.

This month’s chart demonstrates one proxy for fragility, the percentage of companies with net cash balance sheets. Debt magnifies the impact of outcomes, cash on hand dampens them. If you came into this with cash, the probability of your business needing life support is reduced.

Unbeknownst to many shareholders, corporate management have been engaged in a previously implicit, but now very explicit, trade-off between optimisation and resilience.

The story of boardrooms for the last couple of decades has been one of globalisation, financial engineering and shareholder value.

Companies have strived for, and investors have encouraged, operating leaner, faster, more efficiently. From complicated global supply chains to the relentless shedding of ‘non-core’ assets or the outsourcing boom.

Management have been highly incentivised to ride this gravy train with incentive plans tied to return on equity and earnings per share. What an easy win – pay out all your cash, borrow cheap, buyback shares. Stock markets loved it. What could possibly go wrong?

COVID-19 revealed all the flaws. To use the major US airlines as an example, they have spent $43bn on buybacks in the last six years whilst increasing their total debt. The four CEOs pocketed $430m between them[1]. The industry just needed a US government bailout of $25bn and is raising equity.

Corporates, particularly in the US, have become highly evolved to operate in a globalised, stable economy. But the opposite of efficiency is not inefficiency: it is robustness. Highly evolved for one environment, means less adaptable to another: cockroaches outlived dinosaurs.

In the future robustness will be prioritised. That means holding more cash and inventory on hand. It means shorter, local supply chains, diversified suppliers and re-shoring manufacturing; de-globalisation. Companies will care more about other stakeholders, running with less debt and lower shareholder payouts. In a sentence, as Margaret Heffernan put it: ‘just in case over just in time’.

So what does that mean for investors? All of these things are bad for corporate profit margins, but good for ensuring the business can survive another crisis.

The gold star for prudence goes to The All England Lawn Tennis Club which has purchased pandemic insurance for Wimbledon for 17 consecutive years at a cost of £1.5m per annum. This super conservative policy will net a £115m payout just when they need it[2].

Lastly, this is corporate Japan’s ‘I told you so’ moment, having been long criticised for considering a range of stakeholders and for large cash balances, now they look quite clever! At a time when we are seeing unprepared companies make forced dividend cuts across the world, Japan has become a shining beacon of safe income yielding a handsomely covered and growing 2.8%[3] which is why it remains a key part of our portfolio.

1. Ben Hunt ‘Do the Right Thing’

2. BBC News

3. Factset