The year 2020 has been exceptional in its radical push for adaptation in social and economic norms globally. In the last 20 years, we have seen a rapid increase in the movement of people, goods and services around the world. The modern global supply chain has reached a high level of efficiency, bringing heightened economic interdependence between countries. Economic damage from the coronavirus pandemic has revealed the supply chain’s fragility and slowness to react to sudden disruptions. The need to establish a robust form of economic collaboration through modern technology, such as greater digitalisation and robotisation of the supply chain, is becoming ever more important as it is unclear when the ongoing pandemic will end – and whether another might not follow.

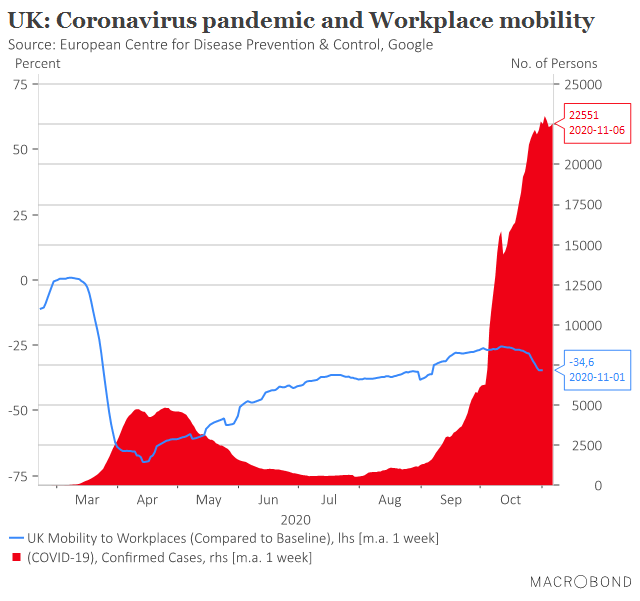

It has been a challenging period for many countries, including the UK, as dealing with the consequences of the pandemic went in parallel with negotiations on a trade agreement with the EU. Looking at how this year has gone might give a good indication to what we can expect in the coming year. The first chart shows how the spread of infection increased at the start of the pandemic in March, to then temporarily subside during the summer. By the end of the year, the UK and many other countries globally were amid a second wave that appears to be higher than the first. The blue line shows how the increase in infections affected mobility to work. Working from home has become a new norm for many people since early this year, and that looks unlikely to change any time soon.

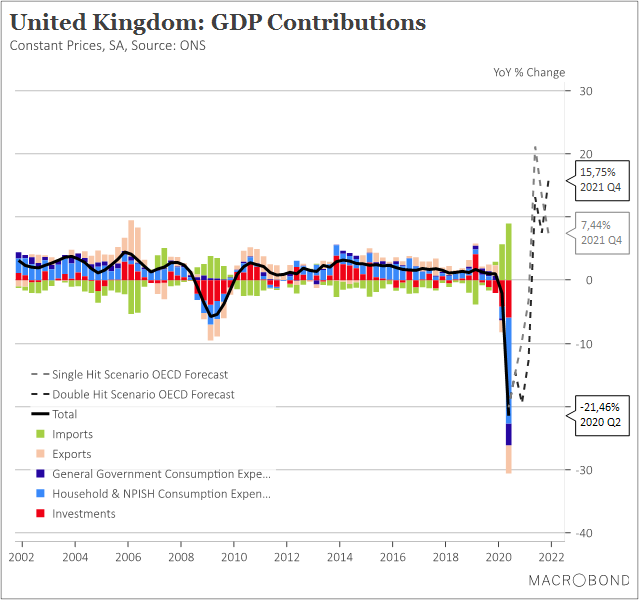

The economic consequences for the UK of the global covid-19 restrictions can be seen in the next chart. Second-quarter GDP figures reveal a serious blow to the economy as all components such as investment, trade, and consumption dropped to historic lows. According to the OECD GDP forecast, a single-hit scenario shows a significant recovery up until the end of 2021. The double-hit scenario in which a second outbreak occurs reveals a dimmer forecast of the economy, as the initial recovery up to Q1 2021 is milder, only picking up more steam later in the year.

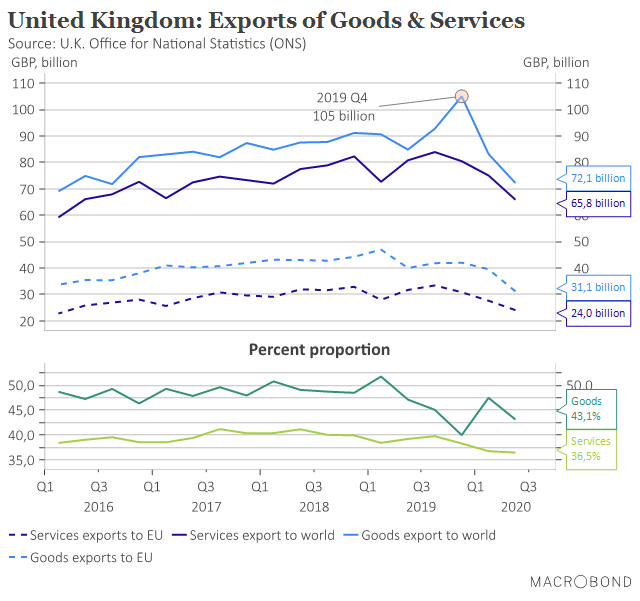

Of course, it also comes down to how the UK manages to secure trade deals with the EU and with other countries. As seen in the chart, exports of goods to the world amounted to £105bn in Q4 2019 before dropping in 2020. A large portion of these goods are imported by the EU, which represents around 43.1% of the total. The value of exported services is also considerable, at around 36.5% of UK exports globally.

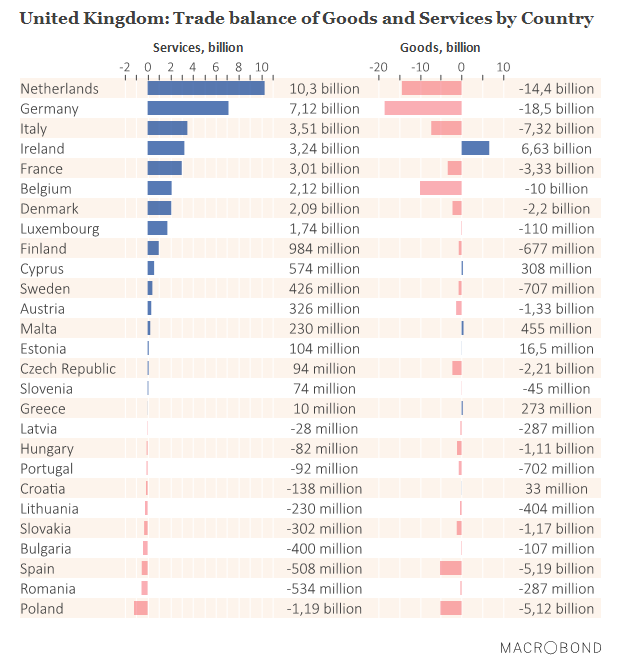

The trade balance between the UK and each individual EU country shows a surplus with most countries in terms of services, but a deficit with many countries in terms of goods. Only Ireland imports significantly more goods than it exports to the UK. The last chart shows that the Netherlands and Germany top the import of services list while also remaining the largest exporters of goods to the UK.

The pace of UK economic recovery next year will be contingent on two factors. It is crucial not only how we mitigate the impact from the ongoing pandemic but also to a large extent whether trade will continue to be uninterrupted after Brexit. For a growing number of countries, protectionist policies have been urged as a solution against external shocks. There are certain challenges accompanying such policies that usually do not adhere to contemporary global economic trends. The goal for the UK and the global economy is to strengthen the durability and adaptability of the supply chain with smart modern technology and diversification. This is something the coronavirus pandemic will accelerate as our work interactions become more digital and production more automated.