Insofar as age has been an issue in the race for the Democratic presidential nomination, the focus has been the advancing years of two of the frontrunners.

Seventy-six-year-old Joe Biden’s circuitous soliloquies and memory lapses leave many wondering if he is fit to be a candidate, let alone the President. Similar questions are asked about Bernie Sanders, 78, who recently had to take time off after being hospitalised by a heart attack. At 70, Elizabeth Warren campaigns with a bounciness that means her boomer status avoids too much scrutiny.

For all the understandable focus on how old is too old, however, the real generational battle is among the voters, not the candidates.

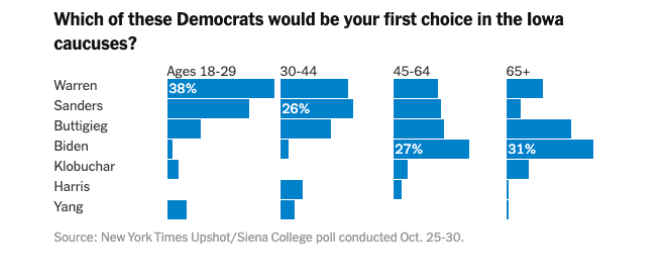

A New York Times/Siena College Iowa poll published last week illustrated the point well. Among likely caucus-goers of all ages in the crucial state, it is a four-horse race, with Warren on 22%, Sanders on 19%, Buttigieg on 18% and Biden on 17%. But, as the graph below illustrates, that race looks very different when you break it down by age. (Astonishingly, Biden is on just 3% among under-45s.)

The results in national polls point to a less pronounced version of the same trend. Biden, for example led a Washington Post-ABC poll released on Sunday on 28%. Among under 50s, however, he sits on just 17%.

Arguably more interesting than Iowa caucusgoers’ preferred candidates were the responses to the poll’s more general question on whether they were more likely to support a candidate who promises to bring “politics in Washington back to normal” or one promising “fundamental systemic change to American society”. 85% per cent of under-30s opted for fundamental change; 70% of over-65s wanted a return to normalcy.

Related to generational considerations is the notion of electability — an already slippery concept made even elusive by Trump’s victory in 2016. And Democrats are no closer to agreeing not just on who is the best person to beat Trump, but exactly what that challenge looks like.

Biden, the frontrunner for the first portion of the race, still leads in national polls but his chances of securing the nomination appear to diminish with every underwhelming campaign event. The former Vice-President is the ‘bump in the road’ candidate, whose account of the last three years is of an un-American aberration, a crease to be ironed out.

For Warren, the Trump question is essentially about political economy. 2016 was evidence that something in the economy, and the rules of that economy, has gone wrong. Success, she argues, lies in rewiring a short-circuited version of capitalism. Andrew Yang’s diagnosis is similar, albeit with a particular focus on industrial decline and automation.

Other candidates see the challenge as spiritual. The idea that Trump reflects a sickness that goes deeper than America’s economic or political health is most explicitly embraced by the zany guru to the stars Marianne Williamson. A more serious envoy for this message is Cory Booker, the senator from New Jersey who prides himself on seeing the big picture and is fond of soaring rhetoric that hasn’t translated into success in the polls.

For Sanders, Trump is as much a blueprint as a challenge. The self-styled socialist from Vermont embraces a left-wing version of the President’s populist style most unapologetically. Not shy of paranoid accounts of a biased media and criticisms of his own party, he is the candidate for socialism with Trumpian characteristics.

Other candidates blend these approaches with mixed results. Kamala Harris’s triangulation has seemed insincere. Pete Buttigieg’s and Amy Klobuchar’s centrist pitches less so.

It is easy for candidates to get caught between riding the wave of discontent among younger voters and reassuring older moderates. The difficulty of squaring this particular circle is evident in Elizabeth Warren’s promise of Medicare for All. The policy is a prerequisite for a candidate appealing to the younger left wing of the party; but as the Massachusetts senator fleshes out her plan to pay for universal healthcare, a drastic overhaul of US healthcare is starting to look like an albatross around her neck.

For now, the candidate who leads the polls is the one who has unequivocally taken the side of older voters, but for how long can that last? Democrats surely stand the best chance of winning with someone that has the ability to both