Literary critic Edmund Wilson posed just this question in a 1945 edition of New Yorker magazine. He was being disingenuous. He didn’t care one jot for Agatha Christie’s wildly successful detective fiction and was irritated that so many did. The last laugh is with Agatha. Forty-seven years after her death she remains one of the best-selling authors of all time. Adaptations of her work continue to grace our theatres, airwaves, televisions and cinemas, not least Kenneth Branagh’s Hercules Poirot mystery, “A Haunting in Venice” which will be released in September.

Given the undoubted popularity of Christie’s creations, it might seem perverse of me to raise Wilson’s question again. But I feel there is still scope for a serious discussion of Christie not just as a superlative constructor of complex plots, but as a chronicler of her times. Writing between 1921 and 1976, Christie was in many ways a mirror of the contemporary mores of her mass market audience, predominantly in the UK. But as her fame grew – and, with it, her ability to travel – her audience reached further afield.

In her works, we read the changing place of working women in society, the traumas of two wars, the Great Depression, changes in technology, tourism and fashion, and perhaps most profoundly, changes in how people casually referred to other races. Furthermore, she tells a lot about which authors were fashionable at the time, and as she became more confident in her craft, she gave us a window into that craft, and interactions with what we would now call “fandom.”

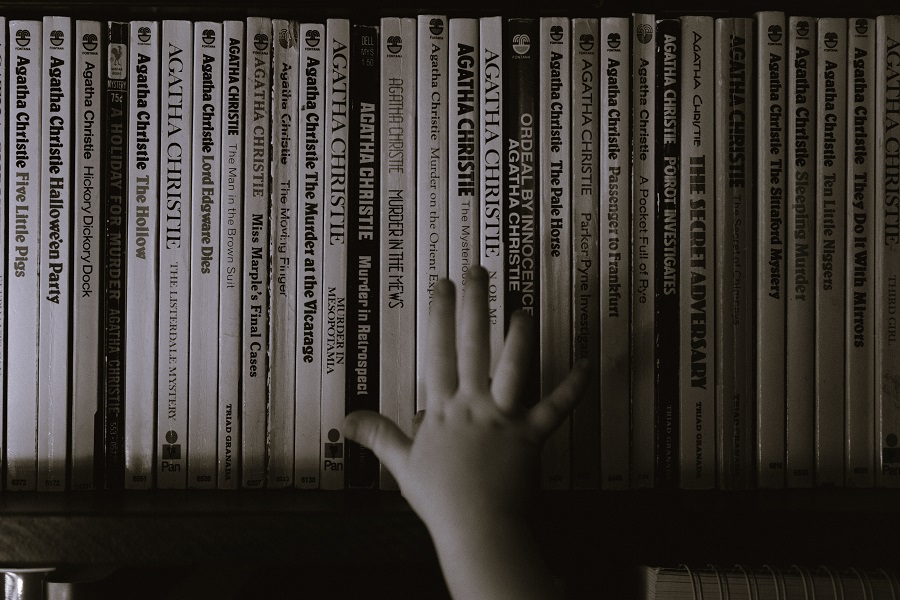

I started re-reading her detective novels, in order, at the start of the year, and have just finished the twenty-first, “Cards on the Table,” originally published in 1937. Here are some of my observations thus far.

The novels of the 1920s are very much those of an author trying to find her voice and mimicking the successful authors of her time. Many of her crime-capers, such as “The Secret of Chimneys,” “The Seven Dials Mystery,” or “Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?” have a sort of PG Wodehouse comic effect, not least the characters of Bundle Brent and Henry Bassington-Ffrench. However, Christie soon tires of this sort of pastiche, and settles into a more straightforward style by the 1930s.

Another early influence is Sir Arthur Conan-Doyle. In the early Hercules Poirot novels, she is very much playing with genre norms he created. Just as Sherlock Holmes has his amanuensis Dr Watson, Poirot has his Captain Hastings. But Christie soon tires of being constrained by the first-person diary style of narration and gets rid of Captain Hastings, despite his public popularity. She ships him off to Argentina and only reluctantly brings him back after the Stock Market Crash. But he is soon replaced by characters such as Colonel Race and the author Ariadne Oliver, both of whom Poirot respects intellectually. This allows us to see a kinder more reflective side of Poirot rather than has habitual mockery of Hastings. I often wonder how Christie would have reacted to the rather intellectually-challenged sidekick being present in practically every one of the David Suchet ITV Poirot dramas.

Another rejection of Conan-Doyle comes even earlier: Christie very quickly rejects the “physical clue” style of detection. Accordingly, Poirot mocks his French counterpart in “Murder on the Links” and makes much of a clue of a piece of pipe. Not for him, crawling around on his hands and knees looking for a certain unique variety of cigarette ash. Rather, Poirot will detect using his “little grey cells” and psychological assessment. However, this means that we should be all the more focussed when a physical clue is presented, and especially when Christie takes the trouble to draw us a map or show us a letter (both of which occur in her first Mrs Marple novel “Murder at the Vicarage”). For those of us who still know how to play bridge, play close attention to the bridge scores in “Cards on the Table.”

Which other popular authors can we see in her 1920s novels? The action-adventures definitely show a familiarity with H Rider Haggard and John Buchan, not least in “The Man in the Brown Suit.” These breathless and somewhat implausible action-adventures have not fared well with modern readers, but were well-reviewed at the time, and tell us something about the popularity of colonial adventures at the time. This was still Imperial Britain at its height.

The 1920s novels are also rather dangerous and subversive in the same way that Evelyn Waugh was, and I do wonder if Christie read Waugh. They speak of soldiers home from World War One with trauma and a dangerous supply of decommissioned arms, and women who were once economically useful and now at a loose end. They also speak of aristocratic Bright Young Things set adrift by families that are asset-rich but cash-poor, and young women that are poorly educated but nonetheless intelligent. This is a world of social and financial turbulence. The early Tommy and Tuppence novel “The Secret Adversary” sees our Young Adventurers searching for work in the early twenties depression by placing an ad in the newspaper and eating at both the Lyons Corner House and The Ritz as money allows. Christie’s heroines are not passive and in need of rescuing. Rather they are smart, brave, mischievous and active. They bob their hair, wear make-up, short skirts and smoke, much to the distaste of old fogies like Captain Hastings. Agatha Christie is clearly on the side of the young women here, as she is a young attractive woman herself.

But there are dangers to this atomised life of adventure. And as we move further through the 1920s into the 1930s, we see the dangers of drug addiction, sexual obsession and sexual exploitation, not least in two of my personal favourite novels, “Peril at End House” and “The ABC Murders.”

As we move into the 1930s, Christie’s writing style settles into one of admirable clarity, brevity and a careful balancing of plot mechanics and psychological motivation. By the 1930s, now in her forties, Agatha is well aware that she is not only financially successful but critically acclaimed, and ranked with the very best of her genre. She finally feels able to comment on the detective genre, not by writing ponderous essays such as this, but by writing about her craft in the character of Ariadne Oliver, a middle-aged author of detective fiction with a messy flat, messy hair, a profusion of ideas, but a clear-eyed view on how hard it is to wrestle them to the ground and actually write a book. Her work is just that – work. Oliver/Christie is not romantic about it. And she is unashamed to talk about her financial motives for churning out a “Christie for Christmas.” Christie is no longer simply an author, but a cultural icon and a businesswoman.

All of this is to say that it rather makes me laugh when people think of Christie as writing safe, comfortable, twee novels set in English villages with quaint old-fashioned characters stuck in social aspic. That setting is valid in “The Mysterious Affair at Styles” and “The Murder at the Vicarage,” but it does not reflect the majority of her work in this period. And why should it when England was changing so violently around her. There are many characters in whom we see great fluctuations in wealth. In “Lord Edgeware Dies” Poirot examines the contents of a lady’s handbag and sees in them the ebb-and-flow of her finances reflected in the quality of what she owns. Nice, young, middle-class girls poorly educated (such as Christie) have to find work. Nice, young men must beg for jobs. The temptation for fraud and petty theft is ever-present, as is self-medicating with alcohol and cocaine.

We also see a more mainstream view of social change. The train is ever present as means of zipping around the country. I marvel at the punctuality of the network and how characters know the relevant ABC and Bradshaw Guide’s timetables by heart. We see the rise of mass tourism to seaside resorts in “The ABC Murders” as well as the rise of a more luxurious type of revitalised Grand Tour in “Murder on the Orient Express,” and “Murder in Mesopotamia.” Motor cars are new, exciting and dangerous. Airplanes likewise. Snobbish Englishmen decry the rise of the crass new money American tourist, and Christie likewise exploits this snobbery with characters that mimic and subvert the trope.

Moving from transport to marriage, while Christie remained rather socially conservative throughout her life, with “Papa Poirot” making many a match, she evidently thought deeply about divorce. In this period, we see her marry, then divorce, and have to fight in court for the custody of her only child given the traumatic fugue state she entered when her husband left her. In novels of this period, we therefore see characters motivated by a desire to remarry but thwarted by the constraints of the Catholic Church (Lord Edgeware Dies) and by the British law at the time preventing divorce from a mentally ill spouse (Three Act Tragedy). The novels of the 1920s and 1930s also show us how Agatha Christie viewed ageing, and the rather alarming anonymity that came with turning from a twenty-something to her mid-forties. As the novels progress the Bright Young Women are seen as people to admire but from the outside. Agatha identifies more with the middle-aged women of her novels, in ways that are painful – the first wife that the husband is tiring of as he seeks a younger companion – and even in the rather portly Ariadne Oliver struggling to get into her little sports car, and self-mockingly conceding that her readers might be rather disappointed to actually meet her.

A close reading of Christie repays in a second way, by signalling the boundaries of what society has deemed permissible to say over the decades, both during Christie’s life, and after her death. I discovered this by mistake, as I have chronicled my linear reread on a community-hosted podcast I co-host. Joined by readers on either side of the Atlantic, with freshly minted paperbacks, and books inherited or purchased second-hand, we have found subtle and not so subtle changes made by publishers to character motivations, speech and indeed chapter titles. In one case, the entire motivation for the murder was changed to reflect differences in American and British divorce law as regards first wives deemed mentally ill.

As one might expect, most of these changes are to eliminate idiomatic speech that would today be considered hateful. It brings one up short to realise just how frequently such words are used in books that are so beloved. In the 1920s, Christie liberally uses the N-word, and the K-word in her novel, “The Man in the Brown Suit,” set in South Africa. In “Death in the Clouds” our two romantic leads bond over their likes and dislikes of seemingly trivial things, but we are shocked to see them bond over their mutual hatred of black people. Perhaps most notoriously, her 1939 novel was originally published as “Ten Little N-words” in the UK but was immediately changed to “And Then There Were None” for the US publication, presumably reflecting contemporary attitudes that the word was still acceptable in England but not in America. How awful. Antisemitism runs throughout the novels too. From the trope of incredibly rich but ruthless Jewish businesspeople, to crude physical caricatures of hooked noses and oily sallow skin. Jewish characters are often mistrusted and untrustworthy.

That said, Christie seems to have a shifting and rather slippery attitude toward racial caricatures and discrimination. In her early 1920s novels she idealises the handsome macho imperial adventurer that she might have read in Rider Haggard novels in her childhood. Her heroes are strong, silent types and women melt in their arms. Christie then married just such a handsome man after many proposals, but he resented her success, cheated on her, and she left him. She then married a younger archaeologist called Max Mallowan who seemed to enjoy her success and travelled widely in the Middle East. Her attitudes changed.

As early as Colonel Arbuthnot in “Murder on the Orient Express” this sort of imperial stalwart is now seen as rather stuffy and old-fashioned. They still utter their racist views but are often exposed as misguided for doing so. The same could be said of the desperately handsome south American adventurer, Major Despard, in “Cards on the Table.” He congratulates himself on being able to remember a black face, while later in the novel Colonel Race declares that Despard could not have murdered a man “because he is white.” Hercules Poirot roundly excoriates him for his assumptions. Moreover, in the same novel, the victim is the self-proclaimed Mephistopheles, Mr Shaitana. He is self-consciously, absurdly “other.” But he is not the murderer.

Christie seems to be saying the evil exists but it is not easily spotted with twirling moustaches. It’s fair to say that in her novels it is rarely the “other” that commits the crime. In fact, Christie often uses the readers prejudices against them, not least in “The Secret Adversary.” Rather, we are better off suspecting the upright members of the middle-class professions; doctors, dentists, vicars – oh, and never trust anyone who can act.

That said, there is probably a PhD to be written about selective censorship in the history of Christie publications, especially those that are over a hundred years old. By the post-WWII years, you can already see mass market paperbacks change chapter titles, most notably in the book I have just begun to read, “Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?” Here, a chapter called “The N-word in the Woodpile” is renamed to “A Wolf in the Manger” in contemporary paperbacks, but to “A Cuckoo in the Nest” in a recent audiobook. Comparing original to current paperbacks shows a lot of censorship of comments that are racist against black people, but all of the antisemitism is left in. A classic case of what David Baddiel so powerfully described in his recently published polemic “Jews Don’t Count.”

My own attitude toward the censorship of fiction is that I would far rather have the text as Agatha wrote it, with an explanatory note at the front or back. I am not sure it does anyone any good to airbrush history. In a country where we often celebrate our being on the “right side of history” in WWII, it brings the reader up short to see just how often and casually the best-selling author of the time used antisemitic tropes. Insofar as Christie reflects our own social history back to us, I would rather have this warning from history starkly laid out before us. When I read Christie, I take great enjoyment from seeing Poirot and Marple puzzle through her mysteries. But at the back of my mind, I always think of Sinclair Lewis’ “It Can’t Happen Here.” I don’t think that’s a bad thing.