For those of us worried about America’s ability to manufacture things, there’s no shortage of worrying indicators to point to. Manufacturing employment has fallen by a third from its peak in 1979, even as the population has grown by nearly 50% over the same period. Storied manufacturing companies like Boeing and Intel are struggling. From machine tools to industrial robots to consumer electronics, the list of American industries where manufacturing capability has been hollowed out is long.

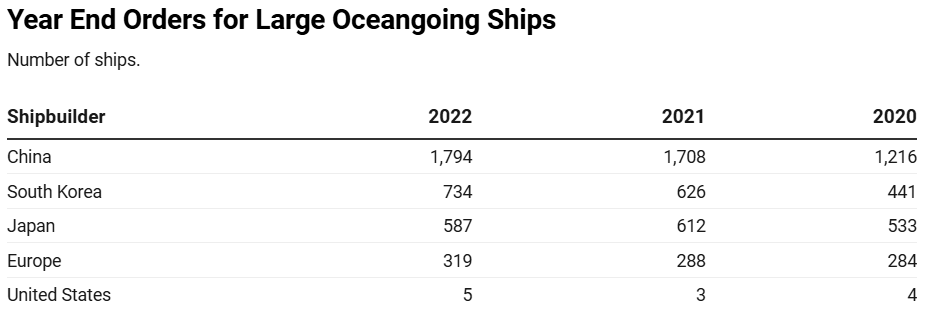

Another worrying indicator is shipbuilding capacity. Commercial shipbuilding in the U.S. is virtually nonexistent: in 2022, the U.S. built just five oceangoing commercial ships, compared to China’s 1,794 and South Korea’s 734. The U.S. Navy estimates that China’s shipbuilding capacity is 232 times our own. It costs roughly twice as much to build a ship in the U.S. as it does elsewhere. The commercial shipbuilders that do exist only survive thanks to protectionist laws like the Jones Act, which serve to prop up an industry which is uncompetitive internationally. As a result, the U.S. annually imports over 4 trillion dollars worth of goods, 40% of which are delivered by ship (more than by any other mode of transportation), but those ships are overwhelmingly built elsewhere.

Source: CRS | Get the data | Created with Datawrapper

In many cases, American manufacturing woes are a story of dominance (or at least success) followed by decline and stagnation. But with shipbuilding the story is different: U.S. shipbuilders have struggled to compete in the commercial market since roughly the Civil War. Outside of a few narrow windows, the U.S. has never been a major force in international shipping. The situation we face today, with U.S. ships costing at least twice as much to build as ships built elsewhere, is not a recent development; it’s been the norm for at least the past 100 years.

Golden age and decline of US shipping

To find a competitive American shipbuilding industry, you need to go back prior to the Civil War, to the era of wooden ship construction. The period from 1840 to 1860 is considered the golden age of American shipbuilding. Thanks to an enormous abundance of wood, and a long tradition of wooden shipbuilding, the U.S. built some of the fastest ships in the world in the form of packet ships and their descendants, clipper ships. When gold was discovered in California in 1848, most of it was brought back east via clipper ship. U.S. shipbuilding was commercially competitive enough that on the eve of the Civil War, roughly 2/3rds of America’s foreign trade was carried on U.S. ships.

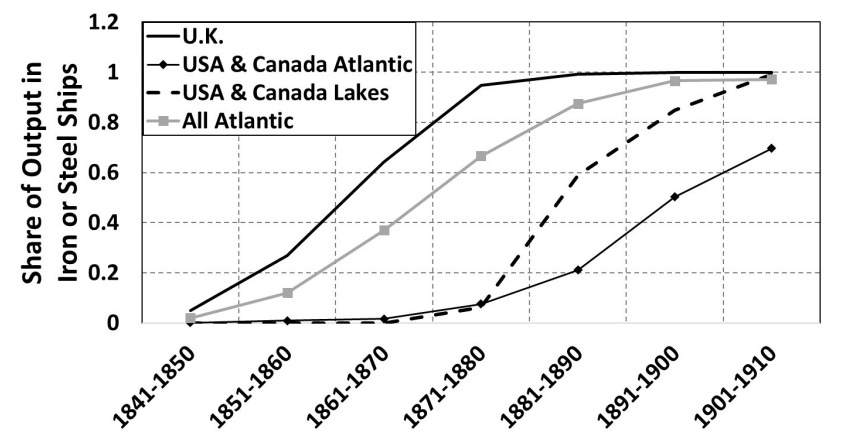

But the wooden ships the U.S. was so adept at building were already in the process of being displaced by iron, steel, and steam. This process did take time. While the first steamships were built at the end of the 18th century, sail-powered wooden ships remained superior for ocean transport for decades. Early steam engines were large, bulky, and comparatively inefficient, and the huge volume of coal required to feed them forced steamships to stop mid-journey at coaling stations, and to be equipped with sails in case coal ran out. Early steamships were also slow, traveling roughly half as fast as the American clippers. But over time, steamship technology improved with inventions like the screw propeller and the compound engine, and the advantage of sail-powered wooden ships was slowly whittled away. By the 1860s, it was clear the future of oceanic shipping was in steam-powered metal ships.

But American shipbuilders were reluctant to transition to building steamships. They were experts in wooden ships, a technology that was still improving, and building a steam-powered metal ship required a totally different set of skills (more akin to what was needed to build a locomotive). Additionally, Britain had what seemed like an insurmountable lead given its proficiency in ironmaking and steam engine construction, a lead U.S. shipbuilders were reluctant to challenge. Thus, despite being the birthplace of the river steamboat, the US lagged behind in the construction of ocean-going steamships. Construction of sail-powered schooners used for coastal trade in the U.S. didn’t peak until the early 20th century, and in 1905 73% of the US’s ships engaged in foreign trade were sail-powered, compared to less than 20% of Britain’s.

By the end of the Civil War, foreign-built steamships were faster and more efficient than U.S. ships for all but the lowest valued cargoes, and by the 1890s the US was essentially no longer competitive as a commercial shipbuilder. By the turn of the century, the fraction of foreign trade carried on American ships had fallen to just 8%, and British shipbuilding output per worker was twice that of the U.S. But while it was not competitive internationally, U.S. shipbuilding continued to flourish as it built ships to serve its domestic market for shipping on rivers, the Great Lakes, and along the coasts. This market was protected from foreign competition by strict cabotage laws, dating from 1817, which required that trade between US ports be done with US-built vessels. While such cabotage laws were common in the early 19th century, by the early 20th century most other countries had relaxed them, leaving the American laws the strictest in the world. These cabotage laws ensured that even as the U.S. retreated from international competition, it continued to have a large shipbuilding industry that served the U.S. market. By the turn of the 20th century, the U.S. had ten times as much domestic shipping tonnage as international, giving it the second largest merchant marine in the world.

WW1 and WW2

But WW1 revealed the risk of having your imports and exports almost entirely carried by foreign ships. As the belligerents in the conflict requisitioned their cargo ships for military purposes and German submarines began to patrol the Atlantic, trade between the U.S. and Europe dried up, and goods piled up on U.S. docks for lack of ships to carry them. To address this, Congress passed the Shipping Act in 1916, which authorized the construction of a $50 million merchant marine fleet. When the U.S. entered the war in 1917, this was raised to an astounding $2.9 billion worth of ships ($71 billion in 2024 dollars).

Funneling these funds into new ship construction required building new shipyards, the largest and most impressive of which was at Hog Island in Pennsylvania; at its peak, Hog Island had 50 shipways and employed 41,000 workers. To accelerate ship production, Hog Island and other government shipyards build standardized ships out of prefabricated components which traveled to the shipyards from all over the country. This allowed ships to be built at unprecedented speed: between June and December of 1918, four government shipyards built as much shipping tonnage as the entire world had produced in an average year before the war. But this speed didn’t come cheap, and the rapidly built ships were on average nearly three times the cost of similar ships built in Great Britain.

And while the construction was fast, it wasn’t fast enough. Of the 17.4 million tons of shipping contracted, only 600,000 of them (3.5%) were built prior to the armistice in 1918. But the U.S. continued to build emergency ships for years after the war was over. By the time the program ended in the early 1920s, the U.S. had one of the largest and most modern merchant fleets in the world, roughly 22% of all world shipping tonnage.

After the war, Congress also passed legislation aimed at strengthening its merchant marine, such as the Merchant Marine Act of 1920 (better known as the Jones Act), which strengthened existing cabotage protections. But this legislation did nothing to resolve the fundamental problems of the U.S. shipbuilding industry, which remained uncompetitive in spite of the huge wartime shipbuilding program. Britain remained the largest shipbuilder in the world, and while the U.S. had caught up in the cost of steel, its labor remained far more expensive. On top of this, the huge glut of ships produced during the war greatly reduced demand for new ships; as a result, between 1922 and 1928 not a single oceangoing ship was built in the US, and many shipyards closed their doors. The onset of the Great Depression in 1929 only made things worse.

To try and support the merchant marine and reignite shipbuilding employment during the depths of the depression, in 1936 Congress passed another Merchant Marine Act, which amongst its provisions included an extremely generous subsidy for American shipbuilders. These shipbuilders could receive a Construction Differential Subsidy (CDS) that covered the difference between American and foreign costs, up to 50% of the cost of the ship; in other words, it assumed that U.S. ships were roughly twice as expensive as ships built elsewhere.

Shortly after this act was passed, the U.S. once again became embroiled in a global conflict that demanded it quickly build a large volume of ships. WW2 largely recapitulated the American experience during WW1, but at a far larger scale. The need to deliver huge amounts of cargoes to Europe, and to replace ships being sunk by German submarines, drove the U.S. to build ships in previously-unimaginable numbers. During the war the U.S. built over 5,000 ships at over 100 shipyards, most of which (2,700) were Liberty Ships. At its peak, the American shipbuilding machine was able to produce the entire pre-war commercial shipping tonnage in just three years.

As in WW1, this shipbuilding feat was achieved by using industrialized methods of construction, most notably large block construction. Instead of building a ship up piece by piece, components would first be assembled into large blocks, which would then be attached together using welding (replacing the older, traditional method of riveting). This enabled extremely rapid ship construction: by end of the war, Liberty Ships took on average just 50 days to complete.

And as with WW1, this exercise in rapid shipbuilding came at a cost. While American shipbuilding efficiency greatly improved during the war (man-hours per Liberty Ship fell from 1.1 million to just 486,000 on average), this was still far less efficient than the British, who could build a liberty-type ship with just 336,000 man-hours. Only a handful of the most productive U.S. yards could match British productivity.

Once again, the U.S. emerged from the conflict with an enormous merchant marine. While after WW1 it had amassed 22% of global shipping tonnage, the enormous scale of the WW2 shipbuilding machine meant that when the war ended the U.S. had 60% of the world’s shipping tonnage.

Post WW2

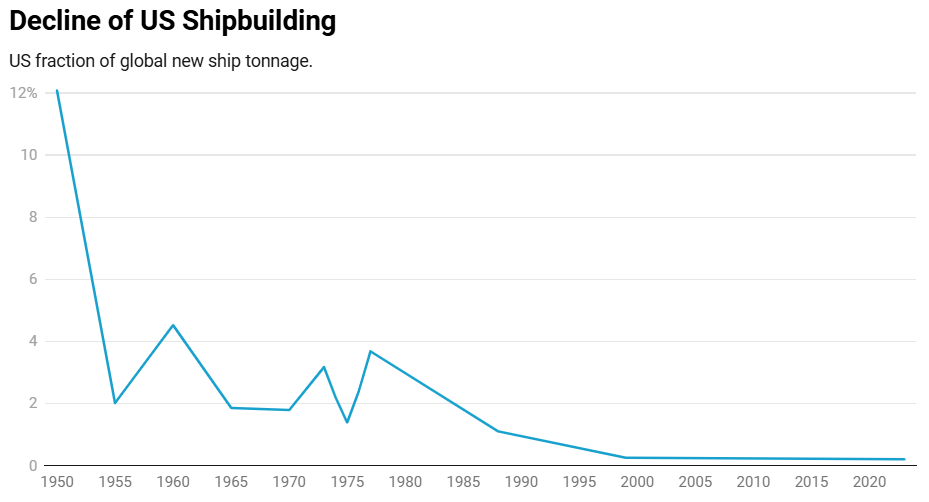

But the U.S. again failed to transform its enormous shipbuilding effort into a successful commercial shipbuilding industry. The huge fleet of cargo ships was quickly sold off to foreign countries and private shipowners. Within three years, Britain, France, Germany and Denmark had completely or nearly completely replaced their wartime cargo ship losses with U.S.-built ships, and the American-owned fraction of global shipping tonnage had fallen to 48%. While the U.S. could have used the opportunity to jumpstart its commercial shipbuilding industry, it chose not to. Even at peak Liberty Ship production the U.S. had not been able to produce ships as efficiently as Britain in terms of labor hours, and after the war both American steel and American labor were far more expensive than in Britain. The U.S. dismantled or mothballed its emergency shipyards, and shipbuilders mostly abandoned the large-block style construction, returning to pre-war methods. Protected by its generous subsidies and often blocked by union rules, American builders had little incentive to try and overcome its labor and material disadvantages with novel, efficient techniques, and U.S.-built ships remained far more expensive than ships built elsewhere. By 1950, the U.S. was once again a marginal producer of commercial cargo ships.

But the large block construction techniques the U.S. developed to build ships quickly didn’t die. Instead, they were brought to Japan by Elmer Hann, a former superintendent at a Kaiser shipyard during the war, now employed by Daniel Ludwig’s National Bulk Carriers. Ludwig wanted to build tankers of unprecedented size, which brought him to the Japanese shipyards at Kure, which had built the enormous battleship Yamato and emerged from the war largely intact. Hann brought his experience with large-block construction, and the Japanese quickly adopted and improved on the techniques, combining them with detailed assembly drawings used in aircraft manufacturing, group technology, and statistical process control methods introduced to Japan by Edwards Deming. Along with support from the Japanese government, large block construction technology allowed Japanese shipbuilding to rapidly improve, and by the end of the 1950s Japan had overtaken Britain as the largest shipbuilder in the world.

In the U.S., on the other hand, commercial shipbuilding continued to decline. Domestic shipping on rivers and coasts, previously the source of the lion’s share of demand for US-built ships, was facing increasingly stiff competition from trucking. Prior to WW2, there had been roughly 400 ships serving the U.S. coastal trade; after the war it fell to 100 and did not recover. To try and prop up the industry, the U.S. passed laws like Public Law 664 (which required half of all certain government-financed cargos, such as food aid, to be carried on U.S. ships), but these did little to change the overall trajectory of the industry.

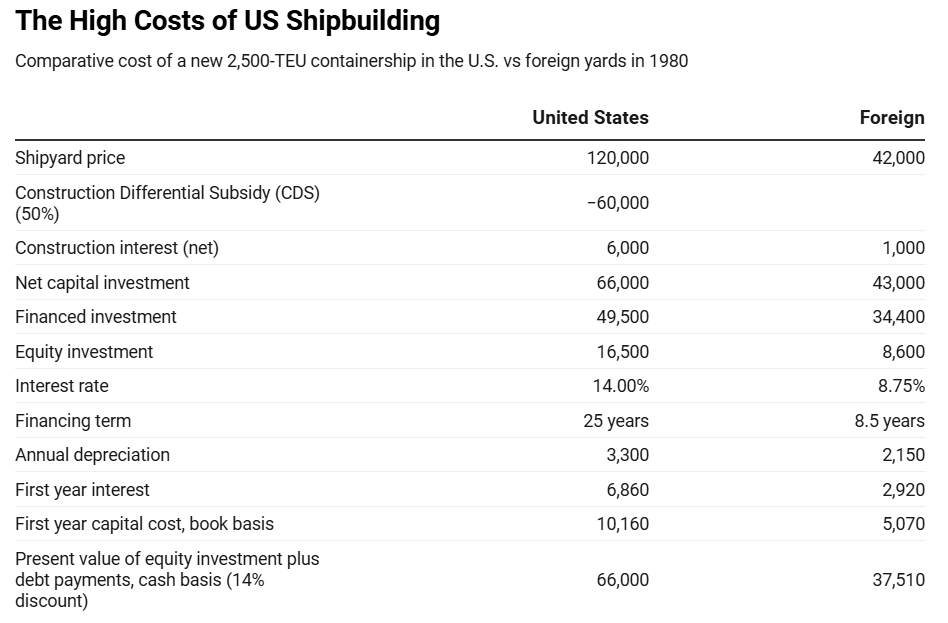

In the 1970s, there was a major attempt to reverse this decline in US shipping and shipbuilding, with the Merchant Marine Act of 1970. The act authorized funds for constructing more than 300 ships over a 10-year period, and extended the 1936 subsidies to encompass more types of ships. To try and incentivize shipbuilders to make their operations more competitive and efficient, subsidies were planned to gradually be reduced over time, from 50% of the cost of a ship down to 33%. The 1970 Act also led to the creation of the National Shipbuilding Research Program, which studied ways to reduce ship costs and construction times.

The result was “the largest peacetime shipbuilding program in U.S. history.” Shipbuilders spent more than a billion dollars modernizing their yards and making capital improvements. Japanese shipbuilding practices were studied, and Japanese shipbuilding firms were engaged to help bring their techniques back to the U.S. A large number of commercial ships were built: some of them, like the recently-invented Liquified Natural Gas carriers, without any subsidies at all. For a brief time, the U.S. was the second largest commercial shipbuilder in the world behind Japan.

But the shipbuilding boom proved to be short-lived. The 1973 oil crisis caused shipments for oil to fall, and the market for tankers and LNG carriers collapsed. In some countries, tankers were sent immediately from the shipyard to the scrapyard without ever carrying cargo. And beyond the petroleum industry, demand for new ships dried up; global ship production fell from 34 million tons in 1975 to just over 13 million tons in 1980. Productivity improvement efforts were only partly successful. One Japanese shipbuilding executive who took part in the program noted that while productivity improved, it had not risen as much as was expected, and shipyards often struggled to adopt the new techniques. In one case, a shipyard building a ship from large block construction found the first two blocks didn’t fit together: parts were misaligned by up to 18 inches. Ship owners near-unanimously noted that the quality of U.S. ships was inferior to those built elsewhere. U.S. construction subsidies were quickly brought back to their full level, but this failed to stop the decline.

The fundamental problem with the construction subsidies is that even with them in place, buying a U.S. ship was still often a bad deal. The subsidies came with strings that made designing and building a ship more difficult, such as the design for the ship needing to be approved by the U.S. Navy. In one case, the Navy insisted that a ship be built with steam turbines instead of diesel engines, which added millions of dollars a year in operating costs. Because the American ships were more expensive to build, insurance on them was much higher, adding even more operating costs. And American ships also took much longer to build, tying up capital for longer periods and reducing return on investment.

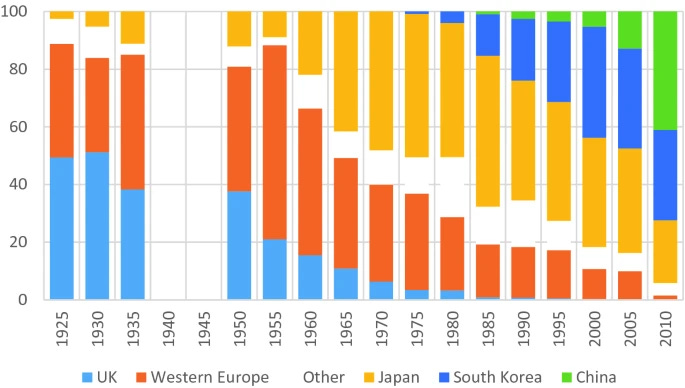

Source: Gibson 2000 | Get the data | Created with Datawrapper

In 1982, the already anemic commercial industry suffered another blow when the Reagan administration eliminated the Construction Differential Subsidy that had been on the books since 1936. Prior to this, the U.S. had been producing roughly 20 commercial vessels a year; over the next eight years, it built a total of five commercial vessels.

During the tail end of the 20th century, American shipbuilding continued to struggle. In the late 1980s, the Navy ordered two new fleet oilers, which two different shipbuilding companies failed to complete; after 5 years and $450 million spent, the two unfinished hulls were placed in layup and never completed. In the 1990s, following the end of the Cold War and reduction in defense spending, a new government financing program for shipbuilders inspired some naval shipbuilders to try and enter the commercial game. When Newport News (a builder of aircraft carriers and nuclear submarines) tried to build several tankers for Greek shipowner Eletson, discrepancies during construction were so severe that Eletson canceled its contract; eventually, half of the ships were completed at twice the original estimate. Another naval shipbuilder, Ingalls, tried to build two cruise ships during this period, but soon they were so far behind schedule and so over budget that the unfinished hulls had to be towed to Germany to completed, requiring a special Jones Act waiver to allow them to serve U.S. ports once they were finished.

Source: Shipbuilding History | Get the data | Created with Datawrapper

Around this time, American shipbuilders decided that their real problem was not high costs or poor productivity, but foreign subsidies that were artificially depressing foreign building costs. U.S. shipbuilders thus began to loudly complain about the unfairness of foreign subsidies, in the hopes that the government would reinstate a more generous subsidy program. Much to their dismay, President Clinton was instead able to secure an agreement with OECD countries to jointly remove shipbuilding subsidies and level the playing field. American shipbuilders (who still had government subsidies in the form of generous mortgage financing programs) quickly decided that subsidies “weren’t so bad after all,” and immediately pivoted to campaigning against the agreement; in the end, the agreement went forward without the U.S.

But in spite of its various tribulations, American commercial shipbuilding was steadily improving. Studies in the early 2000s noted that American shipbuilding productivity was improving over time, with labor productivity increasing by roughly 30% between the early 1990s and the early 2000s. Unfortunately, foreign shipyard productivity was increasing as fast or faster, leaving the U.S.’s relative position as an uncompetitive shipbuilder unchanged. In the early 1970s, the U.S. produced 3% of commercial shipping tonnage. By 1988 that had fallen to 1.1%, and by 1999 it had reached 0.25%.

Source: Davies 2010, CRS 2023, Brown 1989 | Get the data | Created with Datawrapper

This roughly brings us to the modern day. The U.S. continues to produce an insignificant fraction of commercial ships, and the shipbuilding industry it does have is propped up by some of the most restrictive protectionist laws in the world. American ship costs and construction times are far higher than those around the world, and markets that once provided a healthy amount of work for shipbuilders (such as inland and coastal trade) have greatly declined. The number of active shipyards has continued to fall, and the yards that do exist mostly do either naval work or build vessels to support offshore oil drilling. The cost and expense of building American ships, along with the protectionist laws that prevent the use of foreign-built ships, have had a variety of downstream effects, from creating barriers to offshore wind farm construction to failing to insufficient dredging of our channels and waterways.

Notably, these struggles haven’t prevented the U.S. from being a major shipbuilding innovator. Many of the most important advances in ship technology, such as nuclear-powered ships, container ships, LNG carriers, ore/bulk/oil carriers, and large-block construction were all developed in the U.S. But in turning these innovations into competitive industries, America has come up short.

Conclusion

What’s behind the US’s long history of being unable to compete commercially? In looking at the history of US shipbuilding, two major trends stand out. The first is the high cost of inputs, particularly labor and steel. Shipbuilding is labor intensive, and we see a repeated pattern of it moving to countries with low-cost labor: from Britain to Japan, then to Korea, then to China. The U.S., on the other hand, has never been able to leverage low-cost labor: as early as the early 19th century, U.S. labor costs were higher than British costs, and remained so into the 1950s. And while it’s theoretically possible to offset your high-cost labor by being more productive, low-labor cost countries have historically been able to rapidly improve their productivity, making this a difficult race to win. Japan worked diligently to adopt and improve the methods of large block construction and statistical process control, and as Korea grew its shipbuilding industry, it went to considerable efforts to import those technologies and best practices.

We see something similar with steel. While the U.S. competed successfully in the international market when ships were made from wood (which was cheap in the U.S.), it began to struggle when the technology shifted to iron and steel, which in the mid-19th century could be made more cheaply in Britain. Similarly, in the 1970s Japanese steel was cheaper than U.S. steel, and in the 1980s Korean steel was significantly cheaper than U.S. steel. The high cost of U.S. inputs is thus a considerable barrier to successfully competing in the shipbuilding market.

The other notable trend visible in American shipbuilding is cultural. The successful shipbuilding countries often have a strong desire to make their shipbuilding industries internationally competitive. In their book on the history of Japanese shipbuilding, Chida and Davies note that following WWII Japan had a “burning zeal” to make its shipyards competitive with the best in the world, and diligently worked at improving its processes. Korea likewise was strongly motivated to make its shipbuilding industry a successful exporter. One British shipbuilder noted that “if a Japanese shipbuilder said the price was 10, all you would need to do was take that to a Korean shipbuilder and they would bid 9 without looking at the specification or anything else.” It’s notable that successful shipbuilding countries are often island countries or (like Korea) effectively islands that are highly dependent on imports and exports.

The U.S., on the other hand, never appears to have been strongly motivated to make its shipbuilding industry an international success. Historically it has been isolationist, trading much more with itself than it has with other countries. Shipbuilding policies have long been much more focused on sheltering the industry from competition rather than driving to make it successful. Shipbuilding unions have often resisted dramatic changes in shipping and shipbuilding technology. Best practice transfer efforts often appear half-hearted. A Japanese shipbuilding executive noted that if ships were behind schedule, American yards were inclined to throw more labor at the problem, where Japanese yards would ask for the reason behind the delays and resolve the fundamental issues. A recurring theme in The Abandoned Ocean, a history of U.S. maritime policy, is that the U.S. has never been able to marshall the political will to remake its industry along more competitive lines.

Historically, the U.S. has been able to marshall major shipbuilding in times of dire emergency, such as during the world wars, and perhaps it will be able to do so again. But it now faces a potential naval adversary, in the form of China, with dramatically higher shipbuilding capacity, at a time when shipbuilding capability is lower than it’s ever been. The picture is not pretty, and it should concern us all.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.