In 2012, one of the first companies I invested in as a defensive value investor was Centrica, the company behind British Gas.

It seemed like a good idea at the time. Centrica was a leading player in the defensive utilities sector, with a track record of growth and the best brand name a UK-based electricity and gas supplier could hope to have.

But the investment did not work out well.

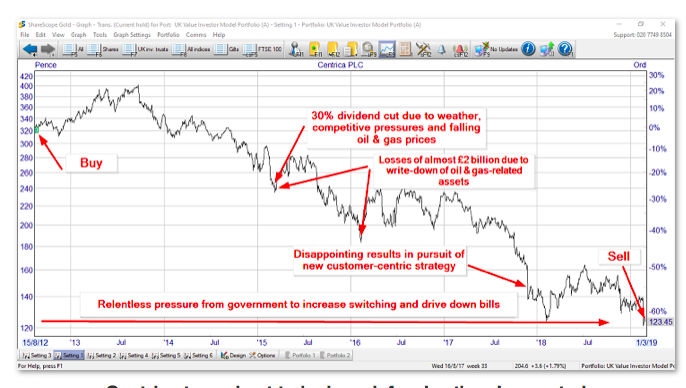

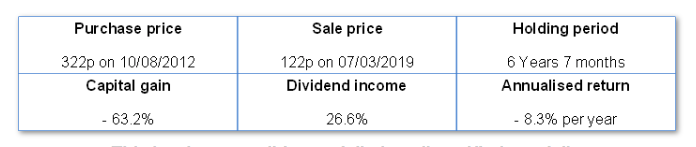

Over a period of almost seven years, Centrica’s shares have lost more than half their value and, even with a tailwind from regular dividends, the investment has lost value at an annualised rate of 8% per year.

In this post-sale review I want to focus on:

(1) Why I bought Centrica in 2012,

(2) why I wouldn’t have bought Centrica if my now much stricter investment criteria were in place in 2012, and

(3) why I’ve finally decided to sell Centrica

But before I begin, here’s a quick snapshot of how Centrica’s share price performed:

Centrica turned out to be less defensive than I expected

And here’s a summary of the final results:

This is why a sensible portfolio is a diversified portfolio

Why I bought Centrica in 2012

Centrica joined my model portfolio and my personal portfolio at a time when the company was very much on the up.

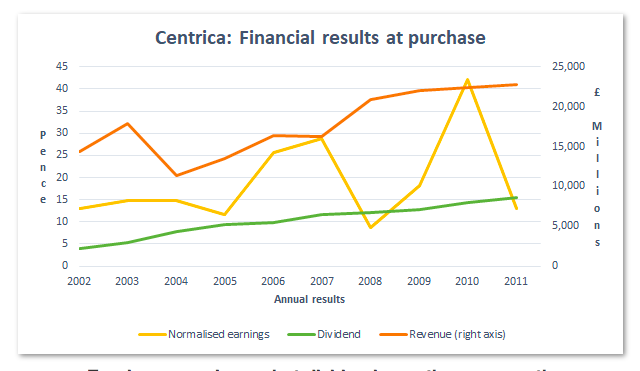

Over the previous decade, Centrica’s revenues per share had grown by an average of 4% per year while the capital employed in the company (representing assets such as gas-fired power stations, wind farms and British Gas vans) grew by an average of about 11% per year.

Perhaps more importantly, the company had grown its dividend progressively by around 14% per year.

For a FTSE 100 company operating in the defensive Gas, Water & Multiutilities sector that was an impressive rate of growth, which you can see in the chart below (showing the three key numbers I looked at back in 2012: total revenues, normalised earnings and dividends per share).

Earnings were lumpy but dividend growth was smooth

Along with this track record of impressive growth, Centrica was also available to purchase at what looked like an attractive price.

Its dividend yield was a very healthy 5%, which compared well to the FTSE 100’s 3.8% yield. Given its above average growth record, the company also had a reasonable PE10 ratio (share price to ten-year average earnings) of 16.3, only slightly higher than the FTSE 100’s 13.7.

Despite this alluring combination of consistent high growth and high dividend yield, Centrica and its share price soon found themselves headed into a long downward spiral.

Over the next few years, a combination of falling oil prices, increasing competition and regulatory change produced a 30% dividend cut, losses of almost £2 billion and earnings which are still barely above zero today.

This raises (at least) two questions:

(1) Was it obvious in 2012 that Centrica was about to run into these problems?

(2) Did Centrica face these challenges from a position of strength or weakness (since strong companies can often benefit from industry headwinds at the expense of weaker competitors)?

Regarding the first question:

I don’t like to invest on the basis of what oil and gas prices may or may not do because they are too unpredictable. So falling commodity prices were not an obvious threat in my opinion. Anyway, I would expect Centrica to be able to deal with this via hedging, as managing commodity price volatility is a basic necessity of its business.

As for increasing competition, I would expect a strong company to benefit from this as weaker competitors lose market share first or exit the market completely.

The same goes for regulatory headwinds, although I am gradually coming round to the idea that heavily regulated industries are more risky than they may at first appear.

That’s because regulators can and often do change the rules of the game quite drastically, and in ways that even a highly competitive company cannot easily cope with (online trading and gambling is currently a good example of this).

Rather than trying to predict the details of the future, I would rather invest in strong businesses which are better able to deal with an uncertain and hostile future than their competitors.

And that brings me to the second question (was Centrica in a position of strength or weakness?):

Well, 2012 was a long time ago and I think I’ve learned a lot since then.

As a result, my investment criteria have evolved to the point where they’re much more demanding than they were seven years ago.

Looking at the Centrica of 2012 using my current investment criteria highlights five major problems which meant the company was operating from a position of weakness, not strength.

Those five problems are what I want to focus on next.

Problem 1) Large recurring ‘exceptional’ expenses

Reported EPS were typically lower than normalised EPS (and sometimes negative)

Until recently I only looked at normalised or adjusted earnings. That’s because they focus on a company’s core business and ignore one-off ‘exceptional’ income or expense items such as gains on the sale of a business or losses from writing down the value of an acquired business.

I now realise that while this can be useful when looking at a single year, it’s a bad idea to focus on normalised earnings over a long period. That’s because the ignored exceptional items are (a) usually expenses rather than income and (b) add up over time.

In Centrica’s case, its normalised net profit for the ten-years leading up to 2011 came to £8.8 billion. However, reported net profits (which include exceptional costs) were just £6.5 billion. So looking at normalised profits essentially ignored £2.3 billion of expenses, which inflated Centrica’s ‘profits’ by 35%.

This obviously has a major impact on the company’s PE10 ratio, with normalised profits making the company appear far more attractively priced than its less flattering reported profits.

Lower reported profits wouldn’t have stopped me from investing in Centrica, but I would have demanded a significantly lower entry price (at least 35% lower) in order to offset the lower earnings.

Problem 2) Relatively weak profitability

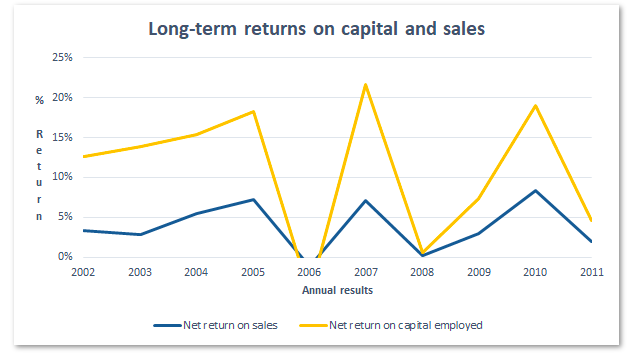

Weak profitability usually indicates a lack of pricing power or cost control

Back in 2012, I didn’t pay much attention to profitability. However, following problems at Tesco and other companies, I added return on capital employed (net profit as a percentage of shareholder and debtholder capital) to my investment checklist in 2014.

More recently, I’ve added return on sales (profit margins, i.e. net profit as a percentage of revenues) as a second profitability metric.

My rules for these two profitability ratios are simple:

Profitability rules

- Only invest in a company if its ten-year average return on capital employed is above 10%

- Only invest in a company if its ten-year average return on sales is above 5%

In 2012, Centrica had an average return on capital of 10.3% and an average return on sales of 3.6%, so its return on capital was barely above my 10% minimum while its return on sales was comfortably below my 5% threshold (I’m willing to allow some wiggle room with these rules, but only a little).

There are two main problems with low profitability:

First, mediocre returns on capital suggests some combination of:

(a) a lack of pricing power (where customers refuse to pay a higher price for the company’s products or services),

(b) an inefficiently run business (for which management are usually to blame) and

(c) unattractive prices paid for past acquisitions (which isn’t so much of a problem as long as management don’t overpay for future acquisitions).

Second, thin returns on sales mean the company has a thin margin of safety between income and expenses. The problem here is that relatively minor downward pressure on income from customers or competitors, or upward pressure on expenses from suppliers, can have a major impact on profits.

In short, Centrica’s mediocre returns on capital and thin profit margins would have put a very large question mark over its entry into the model portfolio.

However, as Warren Buffett has said, there’s rarely one cockroach in the kitchen, and companies that produce low returns on capital often have a hard time growing their capital base.

Problem 3) An ongoing need for large capital investments

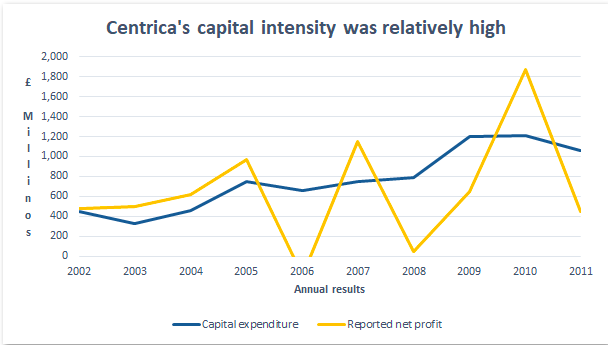

Centrica typically spent more on capex than it made in profit

As an integrated energy company, Centrica was and is active in the exploration, production, storage and processing of oil and gas, as well as the generation and distribution of electricity. These activities all require large, expensive physical assets such as gas-fired power plants, oil rigs and more.

In order to maintain and grow this asset base, the company spent more than £7.5 billion on property, plant and equipment (i.e. capital expenses) in the ten-years from 2002 to 2011. During this period the company’s reported net profits came to just over £6.5 billion, so more was spent on capital investments than was made in profit.

This makes Centrica a capital-intensive business by the definition I use today (i.e. where 10yr average capex exceeds 10yr average profits), and I would rather avoid capital-intensive businesses where possible.

Capital-intensity rule

- Be wary of companies whose ten-year total capital expenses exceed their ten-year total net profits

While this wouldn’t have been reason enough to avoid Centrica, it would have been another ‘warning light’.

It’s a warning light because companies with high capex requirements often find it difficult to grow at an acceptable pace due to the cost of expanding an enormous capital asset base.

But if that’s the case, how did Centrica manage to grow its dividend by around 14% per year over the ten years to 2012?

Problem 4) Growth driven by acquisitions

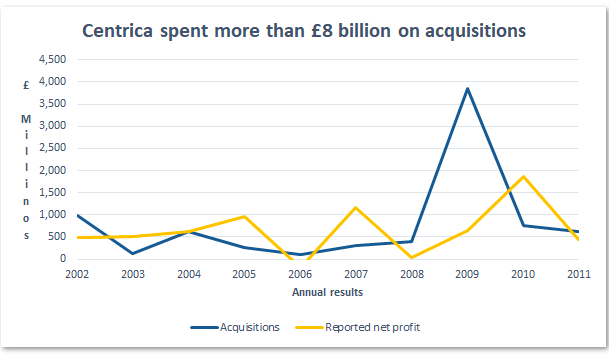

Centrica spent more on acquisitions than it made in profit

One easy way to grow a capital intensive company is to borrow money and use it to buy other companies. This can be exciting for management and can, for a time, drive rapid growth in revenues, earnings and dividends.

In Centrica’s case it spent more than £8 billion in cash on acquisitions between 2002 and 2011, compared to net profits generated over that period of £6.5 billion.

This breaks my rule for acquisitions:

Acquisition rule

- Only invest in companies where ten-year total acquisition spend is less than ten-year total net profits

With highly acquisitive companies, the risks are that:

(1) The shiny new acquired businesses get all the attention while the existing ‘cash cow’ core business suffers from underinvestment;

(2) cash is siphoned out of good businesses in order to support underperforming acquired businesses (to help management avoid losing face), and

(3) the entire company becomes more complex, more inefficient and harder to manage.

As with thin profit margins, this degree of acquisitiveness would have been reason enough to avoid Centrica. In addition, Centrica was suffering from one final problem which is common among highly acquisitive companies:

Problem 5) Large financial obligations

Companies with high levels of debt are almost always worth avoiding and that’s what I’ve tried to do since at least 2008.

However, what constitutes a ‘high level’ of debt is subjective and may vary from one investor to the next, or one company to the next.

In my case, my standards for prudent levels of debt have evolved over the years and are much tougher today than they were in 2012.

Here are my latest rules on corporate debts, including defined benefit pension schemes: Debt rules

- Only invest in defensive companies where total borrowings are less than five-times the company’s ten-year average net profits

- Only invest in cyclical companies where total borrowings are less than four-times the company’s ten-year average net profits

- Only invest in companies where total borrowings plus total pension liabilities are less than ten-times the company’s ten-year average net profits

In mid-2012, Centrica had total borrowings of £4.2 billion compared to ten-year average net profits of £0.7 billion. That gave the company a debt ratio of 6.4, comfortably above my 5.0 limit for defensive sector stocks.

Once again, this alone would have been reason enough to avoid Centrica.

But there was one final cockroach in this particular kitchen. Centrica also has a substantial defined benefit pension plan, which in 2012 had total liabilities of £4.4 billion. This gave the company a combined debt and pension ratio of 13.0, well above my preferred limit of 10.0.

Five good reasons not to buy Centrica in 2012

In summary then, the Centrica of 2012:

(1) Had large recurring ‘exceptional’ costs and was not earnings as much as I originally thought;

(2) had very thin profit margins;

(3) was quite capital intensive;

(4) had grown largely by acquisition and

(5) was excessively indebted especially given its fairly substantial pension liability.

So while I did invest in Centrica in 2012 and I did suffer a prolonged period of negative returns from this investment, I’m confident that with my updated investment process there is zero chance this sort of company will ever get into the portfolio again.

Why I’m selling Centrica now

As Centrica’s performance has weakened and as my stock screen has evolved, Centrica has gradually slipped down the rankings.

It’s been on death row (i.e. one of the five lowest ranked holdings in the portfolio) since the middle of 2018, but I’ve held on because I wanted to see if it was able to turn things around, and because the contrarian in me hates to sell companies when they’re so obviously out of favour.

But enough is enough. Centrica meets almost none of my investment criteria.

If I continued to hold Centrica it would be a choice driven by fear of loss and speculative hopes of a rebound, and neither fear nor speculation are a sound basis for investment.

So for me, the only rational course of action is to sell up and reinvest the proceeds into a company that does meet my now much stiffer investment criteria.

More money has probably been lost by investors holding a stock they really did not want until they could ‘at least come out even’ than from any other single reason. If to these actual losses are added the profits that might have been made through the proper reinvestment of these funds, if such reinvestment had been made when the mistake was first realized, the cost of self-indulgence becomes truly tremendous.

– Phil Fisher

A core business in long-term decline

I am also much more negative about the long-term prospects for centrally generated and distributed gas and electricity than I was a few years ago.

I think that model is in long-term decline and will probably be largely replaced by some sort of decentralised, internet-like peer-to-peer energy network, where most people will be able to produce and consume electricity without much need for big power plants.

Centrica is trying to cope with this changing landscape, but if its core business is in long-term decline then I would class it as a ‘business transformation‘, and I don’t want to invest in transformations (because they usually don’t work).

In summary, I sold Centrica because it has become increasingly clear that the company does not fit my definition of a robust and highly competitive company operating in a market with good prospects for long-term growth.

The proceeds from the sale will, as usual, be reinvested into a new holding next month.

Article originally published here.

John is also the author of The Defensive Value Investor: A Complete Step-By-Step Guide to Building a High Yield, Low Risk Share Portfolio.

His website can be found at: www.ukvalueinvestor.com.