Russia’s invasion of Ukraine last year caused oil and gas prices to surge, triggering a cost of living crisis in many countries, including the UK.

To pay for support for households and businesses experiencing this energy price crisis, the government introduced an additional 25% levy on oil and gas extraction from 26 May 2022. This was increased again in the 2022 Autumn Statement to 35% from January 1 2023. Proposals were also put forward for a separate 45% electricity generator levy.

But recent bumper earnings announcements from large oil and gas companies have called into question how effective these taxes really are.

In 2022, Shell’s annual income to shareholders increased by 211% from US$20 billion (£16.5 billion) to US$42 billion. Similarly, BP reported a 215% rise in profits to US$28 billion, from US$13 billion in 2021. But the UK taxes these companies pay are extremely small compared to the overall amount they pay globally.

Over the winter months, ongoing media reports have detailed how many people are being forced to choose between heating and eating. This raises questions of fairness and has led to calls for further increases in windfall taxes for these companies.

But my research into the UK taxes these companies pay versus the profits they are making right now shows that even larger windfall taxes for energy companies may not make a massive difference to the amounts generated from recent record profits.

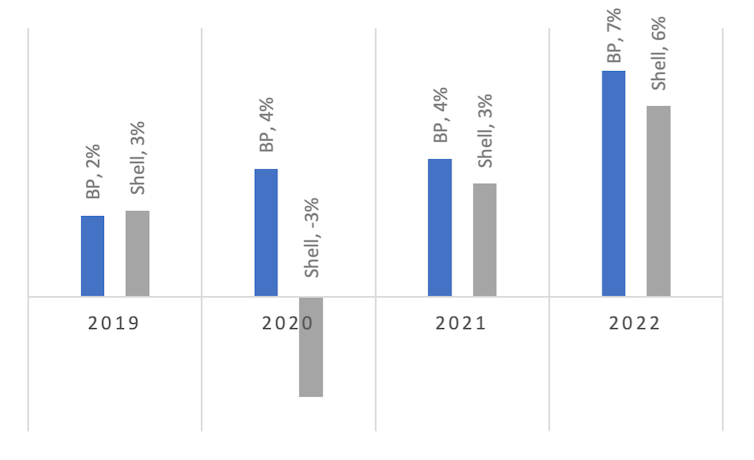

It’s possible to get some idea of this by broadly comparing Shell and BP’s reported profits with their tax contributions. The chart below shows the ratio of taxation to revenue paid by these companies between 2019 and 2022. There have been substantial fluctuations across the years, including a significant jump between 2021 and 2022, suggesting these companies did pay more tax in 2022 – after the 25% windfall tax was introduced.

Revenues made versus taxes paid globally

But it would be wrong to attribute this change to the introduction of this windfall tax in the UK. Although Shell and BP have headquarters in London, they are multinational companies operating in many countries with different fiscal regimes.

UK operations accounted for only 10% of BP’s total revenues from oil and natural gas exploration and production activities in 2021, while Shell’s revenue share was 13% for the whole of Europe. (BP’s financial statements include separate figures for UK, while Shell reports only European figures.)

The tax collected by the UK government doesn’t even come close to these companies’ total global taxes. BP paid the UK only 5% (US$302 million) of its US$6 billion global tax contributions from oil and natural gas exploration and production activities in 2021, while Shell’s tax contribution in Europe was only 2% – or US$473 million of its global US$7.5 billion tax contributions.

Of course, we are still talking about substantial amounts of money. But the income from these levies is unlikely to be enough to offset the £69 billion the UK is likely to spend on energy support schemes.

Tax breaks

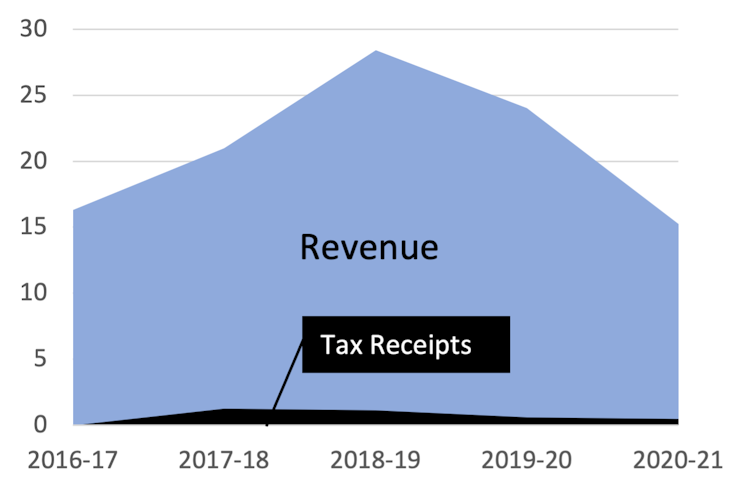

Historically, tax collections from oil and gas producers look quite low compared to their revenues. This chart provides an idea of the vast difference over time:

Tax collected versus revenues from oil and gas extraction in the UK

This is primarily because of generous allowances and reliefs from the UK government. The tax regime for oil and gas production differs from standard corporate taxation in the UK. Companies are liable to higher tax rates and it is “ring-fenced”. This means the extraction of gas and oil is isolated from most of the energy company’s other activities.

So, if such a company makes £100 million in taxable profits from oil and gas extraction in the UK, on paper it would be liable to pay £40 million in ordinary taxes and a further £35 million under the oil and gas levy (after the uplift from 1 January 2023).

The oil companies can be exempt from this liability completely through reliefs and allowances. If this company chooses to invest all its profits (£100 million) in more extraction activities, it would not have to pay £75 million and would receive further allowances to offset future profits the following year, which would total £16.4 million – or even £34.25 million if it invests these profits in decarbonisation activities.

Furthermore, these allowances are not built into the electricity generator levy, showing that the UK government prioritises continued extraction of oil and gas in favour of renewable energy – as I explain in an upcoming paper on this topic.

Why use windfall taxes?

Although there have been many academic studies examining the effects of windfall taxes, the structure of these taxes can differ. As such, there are mixed opinions on whether current levies on oil and gas producers actually work.

Having said that, many experts are against one-off windfall taxes because they could distort a company’s investment decisions (by making other, unaffected parts of the business seem more attractive) and can also increase risk for investors. This is supported by evidence from the UK, where former prime minister Tony Blair’s windfall tax on privatised utility companies was found to have a negative impact on investor confidence and caused these firms to employ fewer people.

So, it might wiser for the UK to move away from hastily introduced windfall taxes towards a more long-term strategy that would help achieve energy security through fiscal stability instead of costly tax allowances and reliefs.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.