A bold prediction, to say the least.

If you looked at Europe in the mid-1600s, you would probably think something along the lines of “Wow, these guys are not going to make it.” Even though the region was already seeing economic growth from colonialism and the expansion of global trade, much of it had also just been devastated by the Thirty Years War, which killed around a fifth of Germany’s population alone. That war, which involved most of the region’s major powers opportunistically sending in mercenary armies who committed untold atrocities on regular people, came on the heels of a century and a half of brutal religious wars and schisms. Politically, Europe was hopelessly fragmented among a vast number of polities, principalities, feudal possessions, proto-states, and so on. And the whole region was menaced externally by the Ottoman Empire, whose proxy pirates were known to enslave Europeans and seize coastal European towns.

We all know how the story goes after that. Just two centuries later, Europe was on top of the world, having invented industrial technology and modern science, consolidated under a few powerful empires, conquered most of the world, and seen growth in living standards unrivaled since the dawn of history.

Europe’s rapid rise from the ashes of centuries of division, war, and poverty provides a vivid demonstration of how a civilization’s potential is not baked into its cultural or historical DNA. Regions that seem dysfunctional are capable of rapid rises.

Just a few years ago, there were few regions of the world that seemed as dysfunctional as the Middle East. Some Middle Eastern countries had oil wealth, but overall living standards were mediocre and pretty stagnant, and there was little domestic technology or competitive industry to speak of. Authoritarianism was everywhere, and strict religious values had produced persistent social inequalities. And most importantly, the whole region was mired in a seemingly intractable morass of wars. The conflicts in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Libya, and elsewhere claimed millions of lives, and displaced more millions. Dictators, rebels, religious zealots, and proxy militias sent by great powers and regional powers alike battled it out on the bloody sands for decades.

And yet when I look at the Middle East today, I’m strangely hopeful. I don’t know if the region is primed for global ascendance the way Europe was in the mid-1600s, but I anticipate significantly better days ahead, for a number of reasons. The most important are the decline of war and the green energy transition, while the demographic transition will also be helpful.

Middle Easterners are getting tired of war

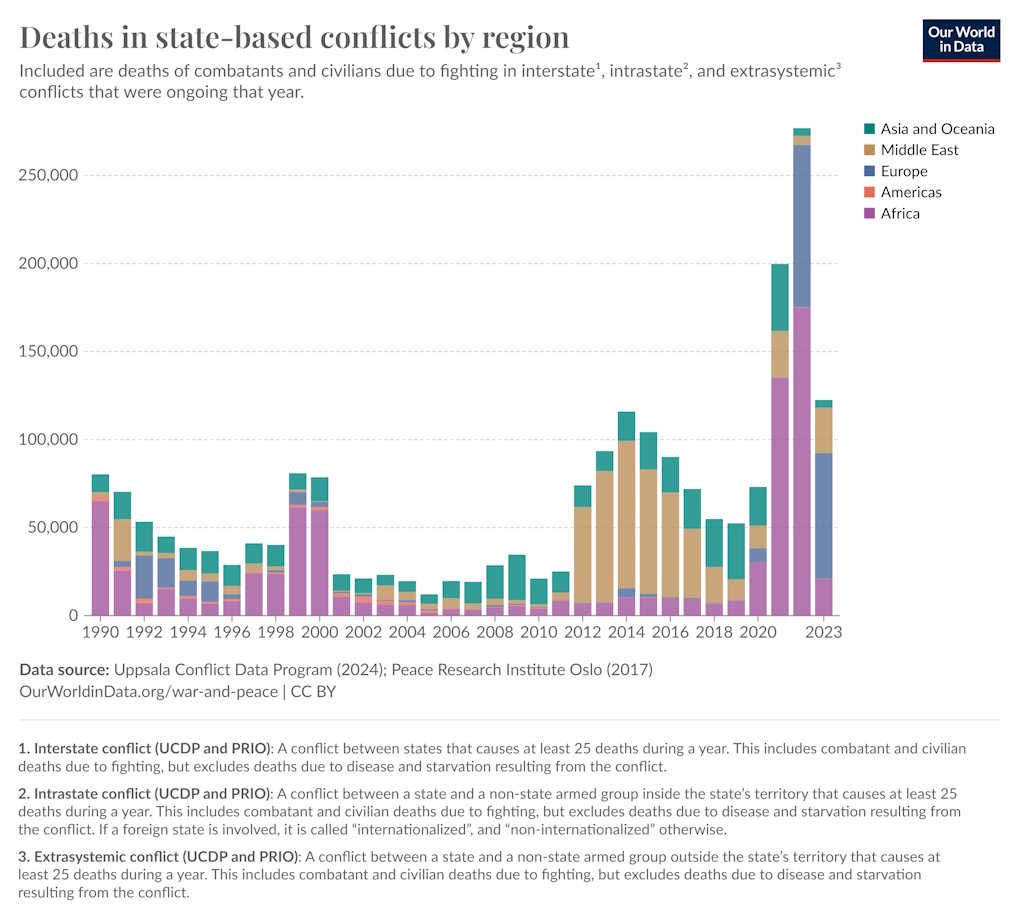

Seven or eight years ago, the Middle East was the center of global warfare — most of the war deaths in the world were happening in the Middle East. But by the 2020s, most of the region’s wars had calmed down to a greater or lesser degree, and other places had become much more violent:

The big news this week, of course, was a ceasefire deal between Israel and Hamas in Gaza. In fact, I’m pessimistic that this deal will hold, and the question of Gaza’s independence — and of Palestine in general — is still unresolved.

But elsewhere, reasons for optimism are stronger. Syria is now largely at peace, after rebels suddenly overthrew Assad’s regime in December. While it’s still early days, the most important rebel group has signaled that its regime will be a relatively moderate, pluralistic, tolerant one, rather than an Islamist theocracy like the Taliban. That might just signal a desire to be accepted by the West, but it also probably stems from the Syrian people being utterly tired of civil war and sectarian strife.

Meanwhile, Lebanon is looking more peaceful and stable, after an Israeli campaign decapitated Hezbollah’s leadership and forced Hezbollah to withdraw from border regions. The Lebanese state has begun to assert its power, and the country’s new president has promised to disarm Hezbollah. Even if he can’t keep that promise, the country will certainly benefit from supreme power no longer being held by an unaccountable militia that constantly insists on provoking wars with Lebanon’s neighbor to the south.

Syria and Lebanon aren’t the only place where peace is creeping in. Iraq is more stable and peaceful than at any point since the U.S. invasion in 2003. ISIS has been defeated. The war in Libya has died down to a large degree. Only in Yemen does war still rage, with the Houthis continuing to attack international shipping and repress the local population.

Besides sheer exhaustion, the Middle East’s sudden experiment with peace has been helped by the retreat of meddlesome powers. A number of the wars were being caused, or at least exacerbated, by Iranian meddling via proxy militias. But with the overthrow of Assad and the devastation of Hezbollah and Hamas, Iran is fast running out of effective proxies. Domestic unrest and Israeli military superiority appear to have helped tie Iran’s hands as well. Meanwhile, Russia, which was intervening heavily in Syria and a bit in Libya, has had its attention drawn elsewhere, and so is now mostly incapable of causing trouble. The U.S.’ role in the region shifted from destructive (the Iraq War) to constructive (helping to defeat ISIS), but overall the U.S. is also less invested in the region than before.

This doesn’t mean the Middle East is about to become a peaceful place, but the fact that it’s moving in that direction suggests that the region’s people are simply fed up with endless, grinding war. That could set the stage for a rapid economic and social recovery, once people and regimes start turning their attentions to more constructive pursuits.

Geography, technology, and demographics are all on the Middle East’s side

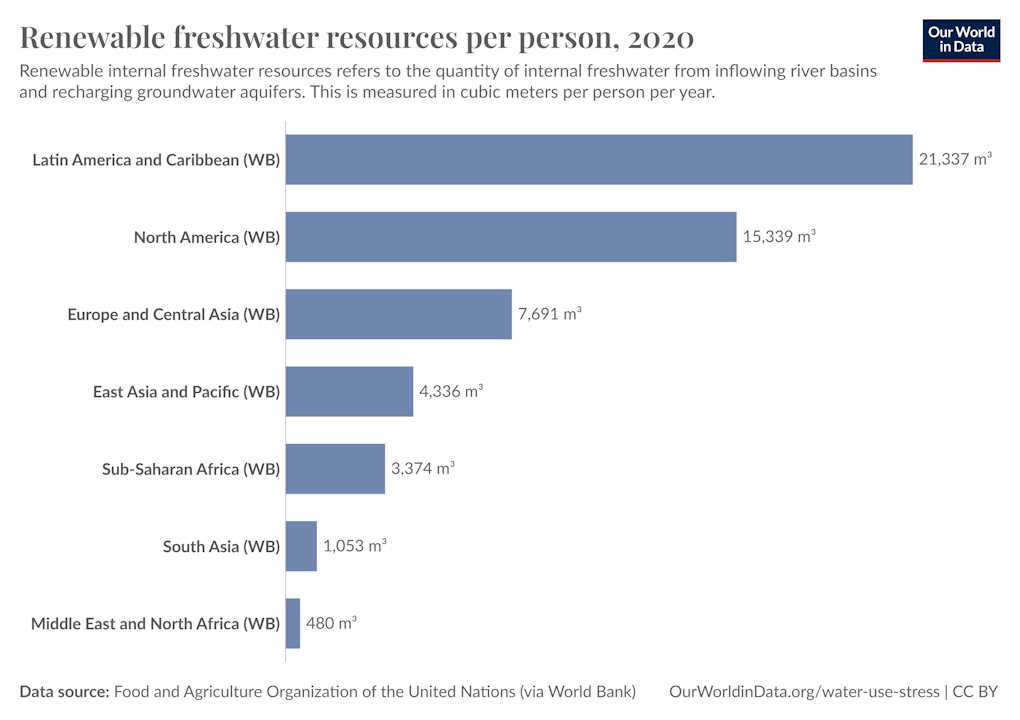

Geography has been a curse for the Middle East for a long time. The region is basically a giant desert, with fewer water resources than anywhere else on Earth:

This seems like a hard constraint on development, but technological innovation is changing the game. As Hannah Ritchie reports, improvements in energy efficiency mean that large-scale desalination is a lot more feasible than it used to be.

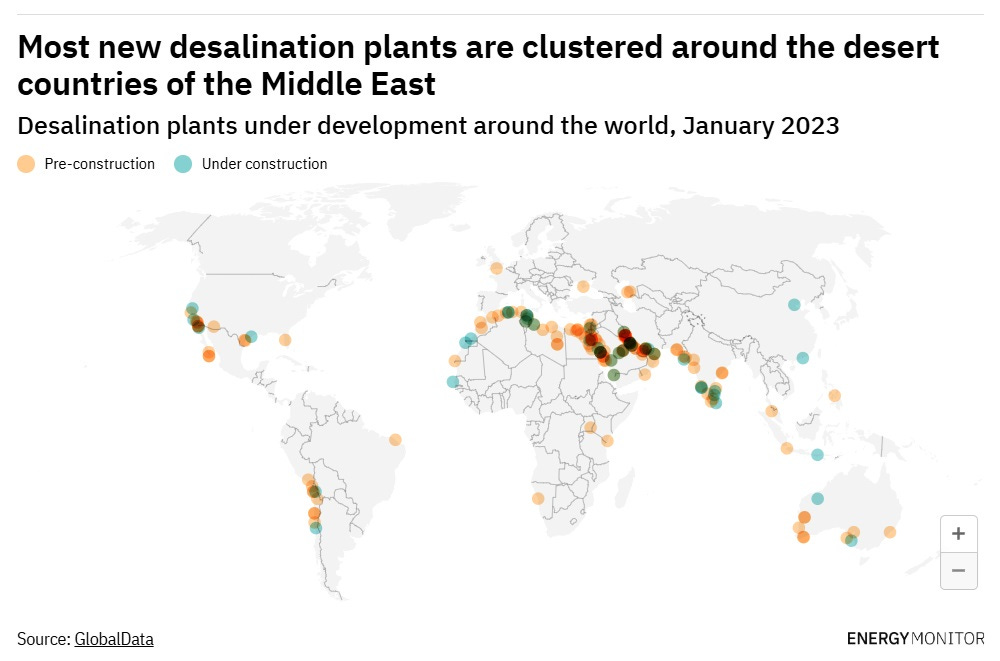

And the Middle East is building a ton of desalination plants:

As Ritchie writes, desalination is very cheap for providing drinking water, but still not feasible for large-scale use in agriculture. But Israel has shown that it can help a lot, because household wastewater can be used for growing crops.

And desalination might soon get even more powerful, because the advent of cheap solar power mean that electricity is about to get much cheaper — especially in sunny areas with a lot of available land, like the Middle East. Casey Handmer has crunched some numbers and found that large-scale solar-powered desalination could soon alleviate much of the water scarcity in America’s southwest; the Middle East isn’t that different.

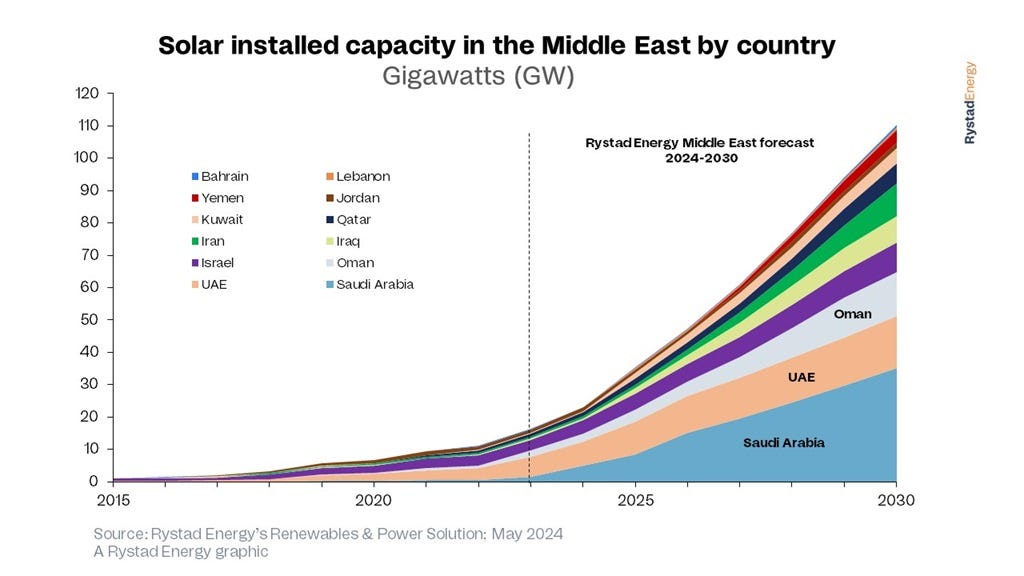

In fact, the advent of cheap solar power is just generally a huge opportunity for a sunny, dry region like the Middle East. Investment in solar is booming:

This will give the Middle East even cheaper electricity than it currently enjoys from oil. And that cheap electricity will allow it to produce a lot of other export goods — especially things that are electricity-intensive to produce, like ammonia and aluminum. Right now, if you want to make something electricity-intensive, you go to China, with its ultra-cheap coal power. In two decades, there’s a good chance you’ll go to the Middle East instead, with its cheap abundant solar power.

This is especially true of Europe, which is located close by, and which could definitely benefit from some cheap energy and other industrial inputs. In the days of the Roman Empire, trade between the Middle East and Europe sustained an economy that was the envy of the world; the advent of cheap solar could lead to another such economic partnership between the regions.

Meanwhile, the dawn of the green energy age is also the end of the age of oil. Petroleum will always been needed for chemical feedstocks, so the Middle East won’t lose its oil industry, but the rise of electric cars will put a huge dent in oil revenues. Fortunately, this could have some salutary consequences for the political economy of the region.

There’s a well-known phenomenon in economics called the Resource Curse, where countries rich in natural resources like oil tend to grow more slowly over time. People argue back and forth over whether there’s a real causal relationship there, but the general preponderance of evidence seems to suggest that the Resource Curse is real.

The leading explanation for the pattern is that the availability of easy rents from mineral wealth allows wealthy rulers to avoid the hard work, financial expense, and political risk of building the kind of institutions necessary for true industrialization — high-quality education, good infrastructure, secure property rights, effective bureaucracies, and so on. Looking at the way aristocratic families, military dictators, and assorted theocrats have siphoned off the Middle East’s oil wealth and used it to fight wars, it’s easy to believe in that theory.

So as oil becomes a less important source of wealth for the Middle East, it could force the region’s regimes to get serious about industrialization. Cheap sunlight is a healthier endowment than cheap oil, because solar power is harder to monopolize by seizing control of a few oil fields. Many of the Middle East’s wars have been fought at least partially over those fields; when solar eclipses oil, one impetus for conflict will diminish greatly.

On top of all that, the Middle East already has some seeds of development in place — the rich Gulf states, and Israel. The Gulf countries can easily provide all of the necessary financing for Middle Eastern economic development, including solar power, industrial buildouts, technological upgrading, infrastructure, and so on. The Israeli technology industry, meanwhile, could invest throughout the region and turn it into a hub for both software and green technology — provided Israel can make a durable, lasting peace with the nearby Arab countries.

And unlike many regions of the world, the Middle East has very favorable demographics. Unlike most of sub-Saharan Africa, it’s not experiencing a destabilizing population explosion.

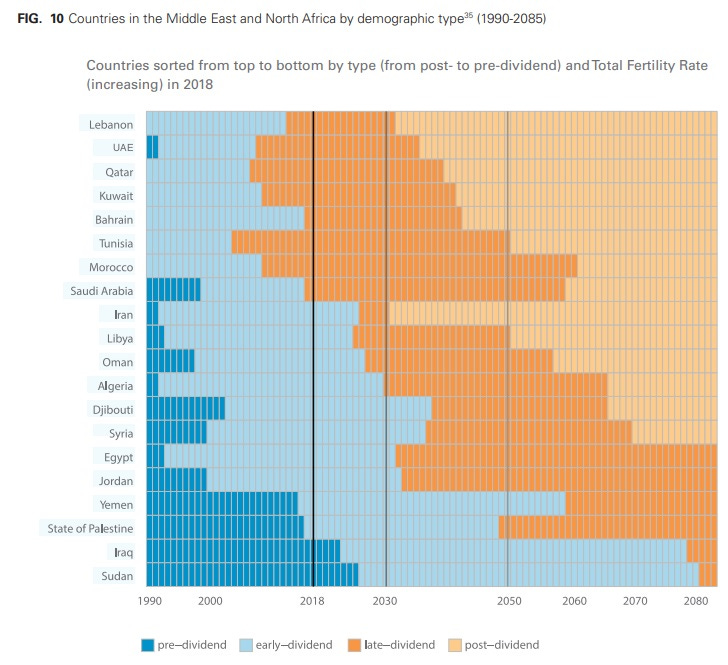

But at the same time, Middle Eastern fertility is still significantly above that of industrialized regions like Europe and East Asia. In other words, its fertility is in the perfect goldilocks region for growth. This is known as the demographic dividend — the period of time when adults have fewer children to look after, but don’t yet have a lot of aged parents to care for, and are thus free to go work in the market. A 2019 report by UNICEF found that most Middle Eastern countries are either experiencing this dividend right now, or soon will be:

In other words, with solar power rising and oil becoming less important, and with its demographics in a favorable position, the Middle East is primed for an economic and political reinvention. The green energy transition may not be quite as momentous an event for the Middle East as the Industrial Revolution was for Europe, but it’s still going to be a big deal.

Half a century from now, the desert may bloom, and the region may be a powerhouse of green energy, industry, and software, rather than the playground of oil sheikhs, warlords, and hyper-religious madmen. I know it’s a bold prediction, but stranger things have happened.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.