Something the Trump administration should probably think about.

Trump is about to be back in the White House, so tariffs are back on the menu. Actually they never left — Biden slapped huge tariffs on a variety of Chinese products, including electric vehicles, chips, and other stuff. But Trump is contemplating tariffs that are far broader in scope — a 60% tariff on all Chinese-made products, and a 20% tariff on all imports from anywhere.

There’s a fundamental difference between targeted tariffs like Biden’s and blanket tariffs like Trump’s. I’m not sure whether Trump’s trade people, including Robert Lighthizer, are aware this difference or not, but it’s important. Like the fact that imports don’t subtract from GDP, it’s something that people who debate trade policy often seem not to understand. But that’s why you have me, your friendly neighborhood econ blogger, to explain it!

What is the purpose of tariffs?

First, let’s talk about two different things you might want tariffs to accomplish.

One goal of tariffs is to reduce U.S. dependence on China — or on the outside world in general — in a specific set of critical industries. For example, if China makes all the batteries, they can just decide to cut you off whenever they want to — as China just did to America’s top drone manufacturer, Skydio. Drones are a key weapon of modern war — perhaps the key weapon. And many drones are battery-powered. So if the U.S. imports all its batteries from China, it sort of puts the U.S. at China’s mercy. Thus, we might want to use tariffs to make sure that China doesn’t make all our batteries.

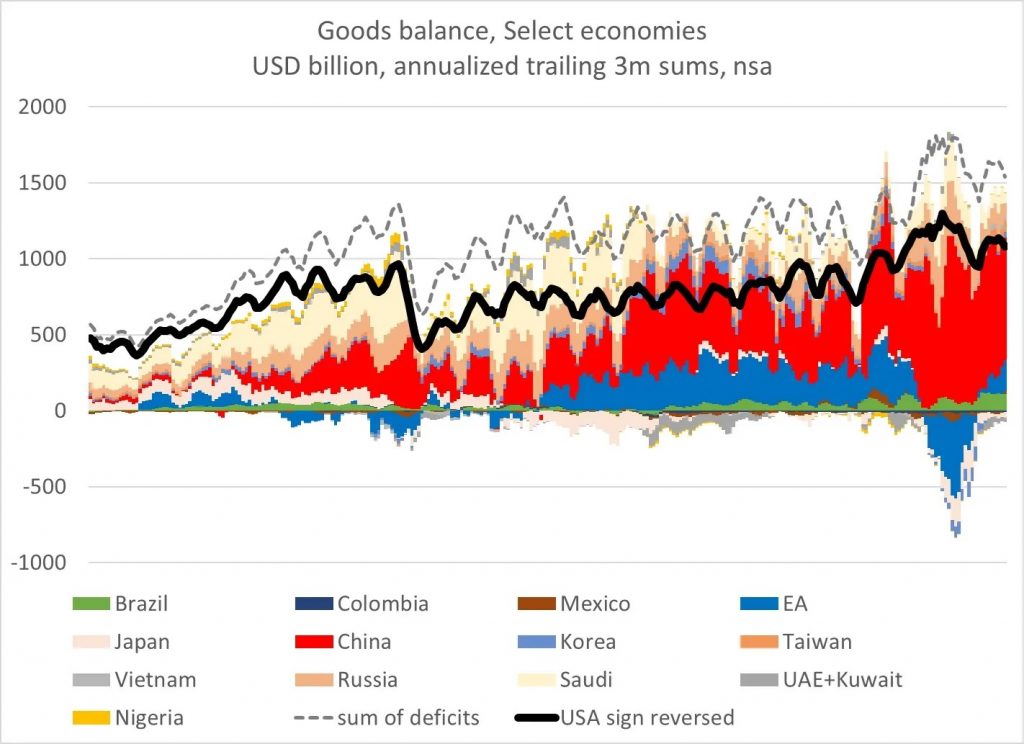

A second goal of tariffs is to reduce trade imbalances. The U.S. runs a very large trade deficit, and China runs a very large trade surplus. In fact, right now, all the countries in the world except the U.S. and China have largely balanced trade. China’s trade surplus accounts for the vast majority of all global trade surpluses, and America’s trade deficit accounts for the vast majority of global trade deficits:

Source: Brad Setser

A lot of countries have balanced trade because they run a trade deficit with China and a trade surplus with America. That doesn’t mean they’re buying stuff from China, slapping a new label on it, and selling it on to America. But what it does mean is that America is the world’s main “country that buys more than it sells”, while China is the world’s main “country that sells more than it buys”.

Many people want to reduce those imbalances. Some people believe (probably correctly) that these big trade deficits hurt U.S. manufacturing, because they rob American manufacturers of key markets overseas. Others believe that global trade imbalances lead to various other economic problems — for example, Michael Pettis, who believes imbalances drive inequality. Still others simply view trade deficits as a “loss” and trade surpluses as a “win”.1 Reducing America’s trade deficit was one of the major goals of Trump’s first term in office.

In fact, both broad tariffs and targeted tariffs have a very hard time reducing trade deficits. But targeted tariffs are capable of reducing U.S. dependencies in specific areas like batteries — in fact, they’re better than broad tariffs for this purpose. Let me explain.

Why broad tariffs struggle to reduce trade deficits

There are actually two reasons that broad tariffs, like the ones Trump is proposing, have difficulty reducing trade deficits.

The first reason is exchange rate adjustment.

When you trade stuff internationally, you have to swap currencies. As anyone who has traveled overseas knows, to buy Chinese goods, you need yuan.2 So if you’re an American, you need to swap your dollars for yuan in order to buy stuff from China. The price at which dollars and yuan get swapped for each other is called the exchange rate.

When the U.S. puts tariffs on China, that reduces U.S. demand for Chinese goods. And that reduces U.S. demand for Chinese yuan, because when Americans don’t need to buy as much Chinese stuff, they don’t need as much yuan.

And when demand for yuan goes down, the price of yuan, in terms of dollars, goes down. This is just basic Econ 101, supply-and-demand stuff. The dollar appreciates in value and the yuan depreciates in value. This is called “exchange rate adjustment”.

Exchange rate adjustment partially cancels out the effect of the tariffs. When tariffs make the yuan get cheaper for Americans, that makes Chinese goods cheaper for American customers. And when tariffs make the dollar get more expensive for Chinese people, that makes American goods get more expensive for Chinese customers.

This doesn’t completely cancel out the effect of tariffs, but it partially cancels it out. It’s like if the government put taxes on pizza, pizza restaurants would cut their prices in response, in order to reduce the number of people who stop eating pizza.

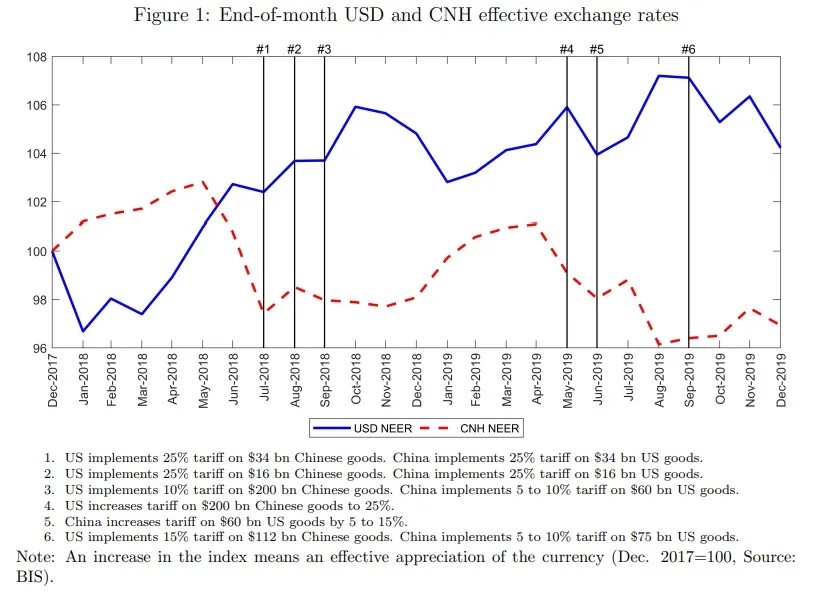

Of course in the real world, there are more than just two currencies, and more than just two countries trading with each other. But if you look at the data, it’s not hard to see the impact of Trump’s tariffs on China in his first term. In this chart from Jeanne and Son (2023), the blue line is the price of the dollar, while the red line is the price of the yuan:

Source: Jeanne and Son (2023)

You can see that when Trump put tariffs on many Chinese goods, the dollar got stronger (in fact, it got stronger a little before the tariffs officially went into effect, because people knew the tariffs were about to go into effect), and the yuan got weaker. China’s tariffs were less impactful, partly because China buys relatively little from the U.S. in the first place. Jeanne and Son guess that “approximately 22 percent of the dollar appreciation and 65 percent of the renminbi depreciation observed in 2018-19 can be ascribed to the tariffs implemented by the US[.]”

Just how much does this exchange rate movement cancel out the effect of the tariffs? In theory, it’s possible for it to cancel out 100%! Exchange rates are pretty flexible — it’s actually pretty easy for everyone involved to say “OK, tariffs made Chinese goods more expensive in America, so we’ll just say that the Chinese currency costs fewer dollars now, so the actual price of Chinese goods for Americans is the same, so everyone in America can just keep buying exactly the same amount as before. Good job everyone, glad we got that sorted out.” And remember that we’re not dealing with a free market here — China’s government will probably intentionally depreciate the yuan in order to avoid losing market share in export markets.

In reality, exchange rates only cancel out part of the effect of tariffs. There’s a bunch of stuff that prevents exchange rates from fully adjusting to the new tax — if you put a billion percent tariffs on everything, you’d probably mostly get rid of all trade, and thus you’d eliminate all trade imbalances. So it’s really an empirical question as to how much exchange rates cancel out tariffs. Jeanne and Son use a somewhat plausible theoretical model to arrive at a number of 30-35%. That’s a substantial decrease already, and I actually think the true number is likely to be higher, especially where China is concerned3. If all of the yuan’s movement against the dollar during this time were due to Trump’s tariffs, it would mean that exchange rate adjustment canceled out around 75% of the tariffs’ effect!

And this is not even the only reason broad tariffs struggle to reduce trade imbalances! There’s at least one more. Broad tariffs also raise costs for American manufacturers, without increasing costs for Chinese manufacturers.

Consider the market for cars. Car companies use a lot of steel and aluminum to make cars. When steel and aluminum get more expensive in America, that raises costs for American car companies. That makes them less competitive, both in the domestic market and abroad.

So if the U.S. puts broad tariffs on everything we import, that will include steel and aluminum. GM and Ford and Tesla will be paying higher prices for steel and aluminum because of the tariffs, so they’ll have to raise the prices of their cars. But BYD and other Chinese car companies won’t have higher costs, because the tariff only applies in America. So the Chinese car companies will gain a competitive edge against the American car companies. That will make Chinese car imports cheaper and American car exports more expensive.

In fact, we have good evidence that this happens. Lake and Liu (2022) study the effects of Bush-era tariffs on steel and aluminum, and found that they hurt steel-consuming industries like the auto industry:

President Bush imposed safeguard tariffs on steel in early 2002…[W]e analyze the local labor market employment effects of these tariffs depending on the local labor market’s reliance on steel as an input and as part of local production. The tariffs did not boost local steel employment but substantially depressed local employment in steel-consuming industries for many years after Bush removed the tariffs. The tariffs also led to a persistent exit of steel-intensive manufacturing establishments, suggesting a role for plant-level fixed entry costs in translating the temporary shock into persistent outcomes.

Lake and Liu are looking at employment outcomes, but the same effect will apply to trade balances too. Across-the-board tariffs make U.S.-made cars and semiconductors and washing machines and refrigerators and farm equipment and robots more expensive, because they raise the cost of imported inputs like steel, aluminum, photoresist, batteries, and so on. But foreign-made products can still get cheap inputs, because they aren’t paying tariffs.

Making American manufacturers pay higher costs than their foreign rivals will obviously cancel out some additional portion of the effect of tariffs on trade balances.

So between these two effects, we can expect Trump’s big “tariffs on everything” to have a disappointingly small effect on the U.S. trade deficit — not zero effect, but less than Trump would like. This is what happened in Trump’s first term, when the U.S. trade deficit didn’t shrink at all4 despite his tariffs:

Now, Trump’s tariffs did have some effect in shifting U.S. deficits away from China, as I’ll discuss in the next section. But in terms of cutting the U.S.’ total trade deficit with the rest of the world, they were a total bust. And when we think about exchange rate appreciation and intermediate goods, it’s not hard to see why that was the result.

Why targeted tariffs can successfully reduce specific U.S. dependencies

I don’t mean to suggest that tariffs are ineffectual — far from it. Targeted tariffs on specific imported products are actually very good at shifting demand away from those imports.

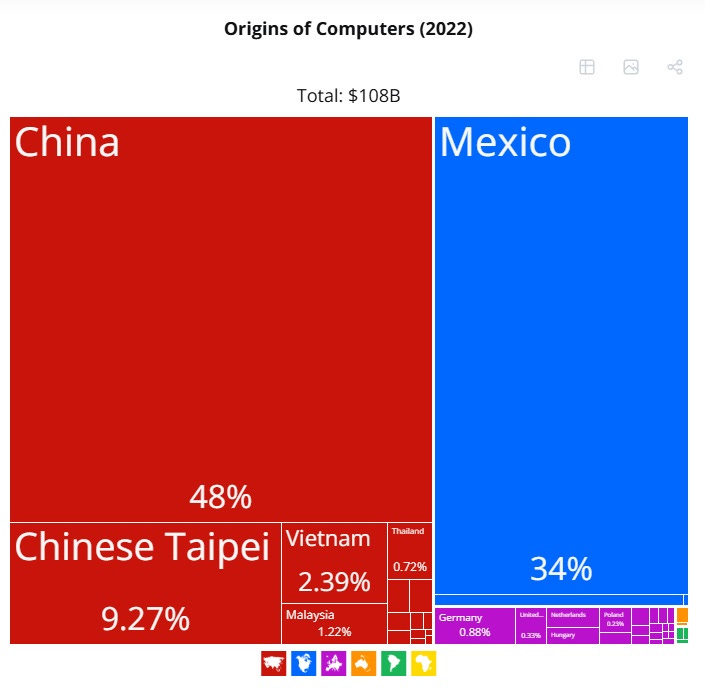

Suppose we put a 1000% tariff on Chinese-made computers. In 2022, the U.S. bought $51 billion worth of computers from China — about 9.4% of our total imports from China. Supposed we used tariffs to increase the price of Chinese computers by 10x. Americans would stop buying any computers from China, and would instead buy computers made in America, Mexico, and maybe Taiwan and Vietnam. In fact, Mexico, Taiwan, and Vietnam are currently our biggest foreign sources of computers besides China, and along with local American factories, they’re probably perfectly capable of ramping up production to meet our needs:

Source: OEC. Note: “Chinese Taipei” is a fake name for Taiwan, which the OEC uses in order to avoid offending the government of China.

Now at this point you may say “Well, but the Mexican-made computers and the Vietnamese-made computers will have a bunch of Chinese chips and screens in them, so we’ll still be importing stuff from China.” And you’re absolutely right! America currently has no good way of assessing how many Chinese components are in the finished goods that we import. Similarly, if we taxed imports of Chinese batteries, we wouldn’t currently be able to apply those tariffs to Chinese-made batteries contained in Mexican-made cars or Vietnamese-made phones.

But suppose we improved our data so that we did know which parts came from where. Then we could use tariffs to completely eliminate Chinese manufacturers from our chip supply chain, or our battery supply chain, or whatever.

And targeted tariffs are much more effective than broad tariffs at accomplishing the goal of securing specific supply chains. One reason is that targeted tariffs don’t have nearly as big an effect on exchange rates as broad tariffs.

If you put a 1000% tariff on Chinese computers, that only affects 9.4% of the U.S. demand for Chinese goods. That’s not going to have a huge effect on exchange rates. U.S. demand for Chinese goods overall won’t fall much, but it will shift to other stuff — plastic, clothes, broadcasting equipment, machinery, or whatever. Whereas if you put a tariff on all Chinese goods — the plastics and the clothes and the broadcasting equipment and the machinery and everything else — the exchange rate will shift by much more, which will cancel out a big chunk of the impact on any specific imported good.

Also, targeted tariffs avoid the problem of intermediate goods that I talked about in the previous section. Yes, if you put a 1000% tariff on Chinese batteries, that will hurt American EV manufacturers. But if you think the battery supply chain is more strategic than the EV supply chain — maybe because batteries also go in drones — then maybe this is OK. Targeted tariffs are like a scalpel that allows you to slice out exactly the types of imports you don’t want, while leaving the less strategically important stuff intact.

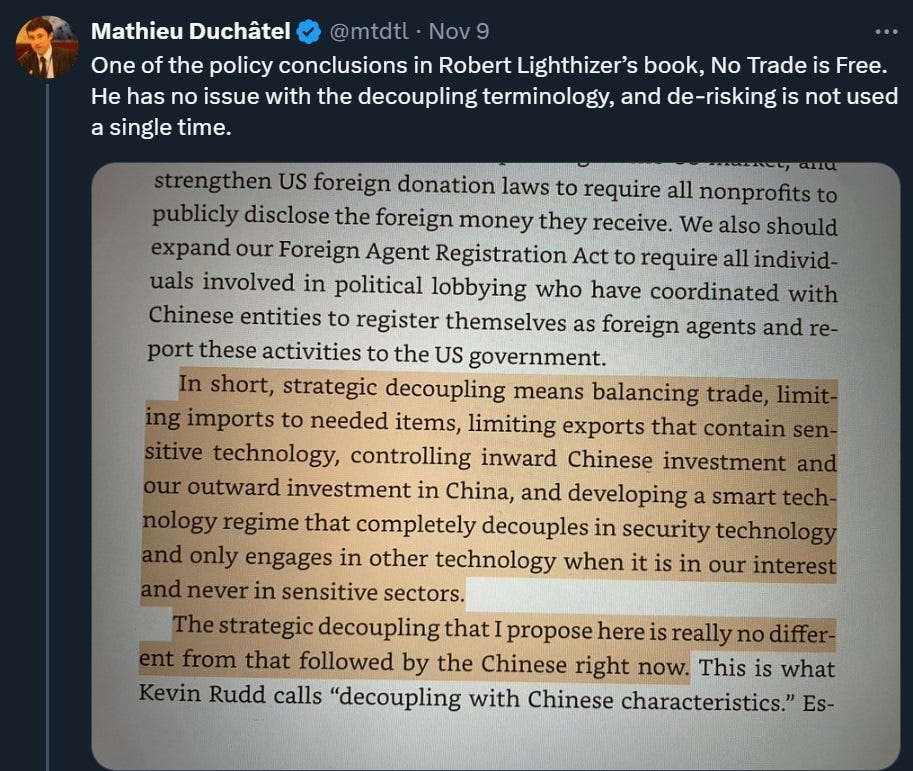

So while targeted tariffs won’t reduce trade deficits, they’re very effective if your goal is to secure certain strategic supply chains. Fortunately, Robert Lighthizer is probably thinking about this, as evidenced by this passage from his book, No Trade is Free:

But this means that Trump’s 20% tariff on all imports from all countries would actually weaken the effect of his 60% tariffs on China! If we only tax Chinese imports, we can shift demand away from China to other countries. But if we tax imports from everywhere, the dollar will appreciate, which will cancel out some of the impact of the China tariffs.

So if what the U.S. wants is to reduce its bilateral trade deficit with China, it shouldn’t put tariffs on imports from other countries. Trump’s 20% across-the-board tariff idea wouldn’t reduce our trade deficit meaningfully, but it would make it harder to shift our supply chain out of China.

So how do you reduce global trade imbalances?

Anyway, that’s all well and good. But suppose we really do want to reduce the U.S. trade deficit. How do we do that? And how do we do it without kneecapping our own manufacturers?

I’ll write a lot more about this, but the short answer is to reduce trade deficits, you need to depreciate the U.S. dollar. Remember how a more expensive dollar makes U.S. exports uncompetitive while encouraging Americans to buy more foreign-made products? Well, if you’re going to reduce the trade deficit, you need to counteract that somehow.

Stephen Miran of Hudson Bay Capital has a good post explaining that the real problem here is the U.S. dollar’s status as the world’s reserve currency. Here, from X, is the upshot:

The truth is that the “strong dollar” is probably the root cause of America’s chronic, persistent trade deficits. U.S. leaders have a choice — a strong dollar, or a strong manufacturing and export sector. So far, we’ve always chosen the former. If Trump really wants to get rid of the U.S. trade deficit, he’s going to have to dump this long-standing policy. But that’s a topic for another day.

This article was originally published in Noahpinion and is republished here with permission.