Falling property prices and mortgage approvals since last autumn are the start of a sustained correction in the housing market, in our view. An average of the Nationwide and Halifax measures showed prices in January down 3.5% from last summer’s peak, the biggest drop over an equivalent period since 2009. And approvals ended last year at the lowest level since 2009, excluding the pandemic period.

These moves are the consequence of several adverse forces. Mortgage rates have increased significantly, household real incomes are falling, affordability remains stretched, and demand is probably suffering from some potential buyers delaying purchases in expectation of further price falls.

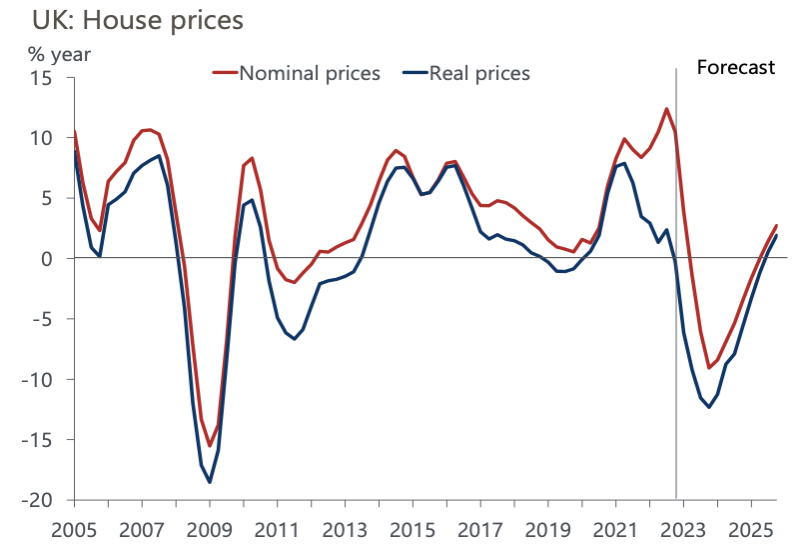

We expect a peak-to-trough drop in prices of 10%-15%. In cash terms, this would take values only back to the level in mid-2021, but high inflation means the real-terms fall will be more substantial (Chart 1).

Chart 1: We expect a sizeable, real terms fall in house prices, though less severe than in 2008-2009

While we don’t anticipate a crash, a downturn in the housing market is one factor behind our view that the UK economy will be in recession for part of this year. A weaker housing market will likely have a direct effect on the economy via less construction activity. Lower prices will squeeze builders’ margins, leading to some projects becoming increasingly unviable and being shelved.

Certainly, the sharp drop in housing transactions in the early stages of the 2008-2009 recession was followed by household goods sales falling sharply. However, the correlation between the two series between 2010 and 2019 was weak, and probably partly a consequence of a persistently lower level of sales, post-financial crisis. And household goods sales account for only around 6% of total consumer spending.

Moreover, unlike the last time house prices fell on a sustained basis in the late 2000s, we don’t expect the impact on households’ wealth to be compounded this time by falling equity prices and financial wealth.

Developments in another potential channel from the housing market to consumer spending – housing equity withdrawal (HEW) – also suggest a more muted effect than in the past. HEW involves homeowners using rising house values as collateral for personal loans or freeing up cash by trading down their property. This was an important prop to consumption during the UK economy’s expansion in the 2000s, with HEW peaking at the equivalent of 7.5% of nominal household incomes in 2003.

But HEW has been heavily negative since the financial crisis, bar a few quarters during the pandemic, despite a strong rise in house prices. In other words, households have put more money into the housing market, for example, through house deposits or overpaying mortgages, than they have taken out through re-mortgaging. This probably reflects tighter, post-crisis, mortgage regulation, a sharp decline in interest-only home loans and more financially cautious households.

A housing market downturn is likely to result in HEW becoming more negative, as structural factors that have held it down are magnified by a fall in house prices. But that HEW has offered no sustained positive impulse to consumption for over a decade means a drag from this source should be much less than during the last downturn in the late 2000s and early 2010s.

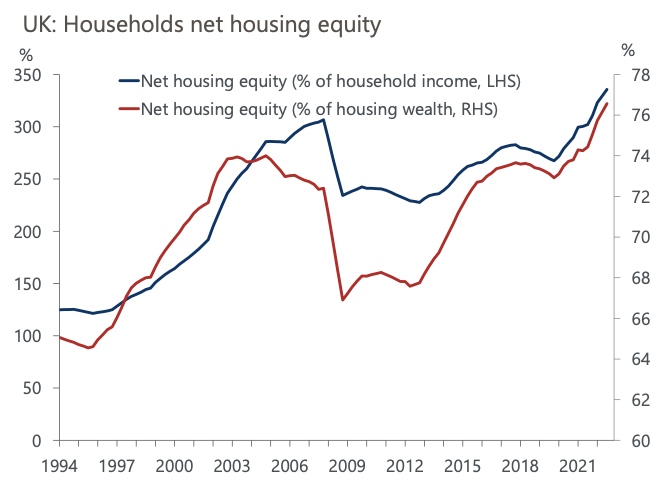

Homeowners have entered the current downturn with an unusually high level of housing equity. This should also soften the impact of falling prices on consumption compared to previous cycles, by reducing pressure on some households to reduce their spending to repay some debt. As of Q3 2022, households’ aggregate housing equity (i.e., housing wealth net of mortgage debt) stood at a record high relative to both gross housing wealth and incomes (Chart 2).

This reduces the risk of negative equity and should limit the number of households who, faced with an expiring fixed-rate mortgage and little or no equity in their home, are forced to revert to their lender’s – typically more expensive – standard variable rate.

Chart 2: Rapid rises in house prices boosted net housing equity in 2022 to a record high

Higher equity levels may also give some borrowers more flexibility to switch temporarily to interest-only mortgages. Of course, this shouldn’t disguise the fact that mortgagees are experiencing, or set to experience, a major rise in debt-servicing costs. But the backdrop to this could have been a lot worse if equity levels had begun at a much lower level.

Still, a sustained fall in prices has consequences for the banking sector, and consequently, the wider economy. Falling property values risk initiating a negative feedback loop in which lenders respond by tightening credit supply, reinforcing the housing market downturn, and eroding borrowers’ confidence and creditworthiness. Indeed, the BoE’s latest credit conditions survey showed the balance of lenders at the close of 2022 reporting the highest fall in the availability of secured credit to households since Q3 2008, excluding the pandemic period.

However, the UK banking sector is far better capitalised now than in the run-up to the financial crisis. And lenders have been stress tested by the BoE against a much bigger – 31% – peak-to-trough fall in prices than we’re forecasting. What’s more, our expectation of a modest peak in unemployment should keep forced sales down. Lastly, our Banking Sector Risk Index (BSRI) suggests that UK banks are less vulnerable to housing market crashes than lenders in many other major economies.