If certain criteria are met, this writer thinks so.

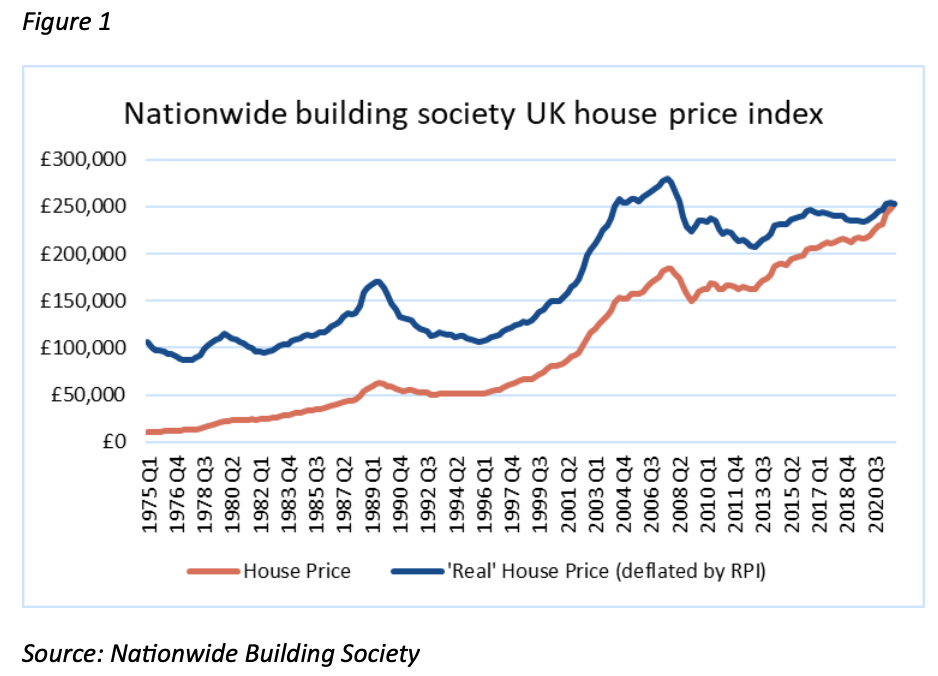

For those who are persuaded that we are still in the early stages of an inflationary resurgence, rather than the mature phase of an inflation spike, the search continues for protective assets. Residential property – meaning the composite of the dwelling and the land on which it sits – has long enjoyed a preferential status in the public mind, as the cornerstone of a household wealth portfolio. A lazy and complacent post-War belief in the resilience of housing assets during recessions and crises was shaken when UK average house prices fell by 37% in real terms between the second quarter of 1989 and the fourth quarter of 1995 (figure 1). The reputation of residential property was dealt a second blow in 2008 when the sub-prime segment of the US housing finance market exploded, triggering a devastating global financial crisis (GFC). Real UK house prices fell again: a 26% drop from third quarter 2007 to first quarter 2013.

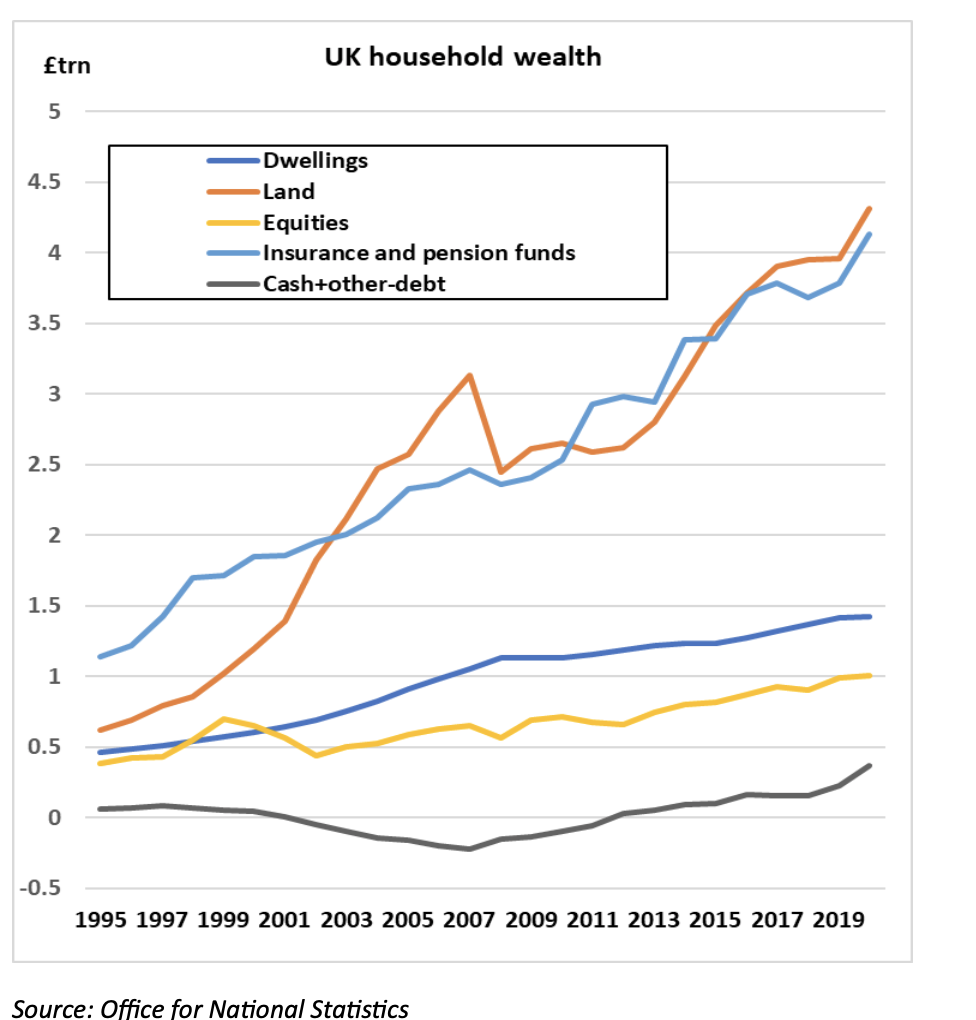

The rollercoaster ride for property owners since the late-1980s helped to propel a diversification of household wealth into financial assets, whose share rose to 61% in 1998. The bursting of the tech-focused millennium equity market bubble sent the pendulum swinging the other way, regenerating the appeal of tangible assets, whose share peaked at 59% in 2007. Then, the GFC hammered land valuations, setting the scene for another rebalancing towards financial wealth.

“Favourable trends in asset prices have been sustained by central bank policies of financial repression”

As figure 2 illustrates, despite the equity market debacles of 2000 and 2008, pension and insurance funds have delivered a remarkably smooth accumulation of wealth for their beneficiaries over the past 35 years. The secret of their success, arguably, lies in the prevalence of a negative contemporaneous correlation between bond and equity returns, meaning that a blended portfolio of bonds and equities would weather most market shocks. However, this stellar performance was achieved in the special circumstances of secular disinflation, falling nominal interest rates and a rising share of factor incomes accruing to entrepreneurs. Latterly, favourable trends in asset prices have been sustained by central bank policies of financial repression, whereby nominal government bond yields and corporate credit spreads are restrained and credit defaults, suppressed. Over the past 12 years, land valuations have been carried along by the same fair winds.

The conventional wisdom on real estate resilience in the face of generalised inflation is based on two key assumptions. First, that income growth will adjust to higher price inflation – either in a pay bargaining framework or a formal indexation process. Second, that property valuations will increase in the context of rising incomes and higher replacement (rebuilding) costs. The underlying assertion is that real estate is either a superior asset or a neutral asset, but it is not an inferior asset. Across the broad spectrum of the income distribution (but not at the upper extreme), as households become richer, they upgrade their housing requirements at least in line with their incomes.

Figure 2

However, there is a third important consideration: the relative outlook for real estate assets as compared to financial assets. To the extent that a transition to higher inflation is (more) damaging to real returns on fixed income securities and equity investments, then real estate is favoured as an alternative and protective asset. The argument is that, quite apart from owner-occupier property, real estate assets should form a significant component of an investment portfolio in inflationary times. My former colleague, Yvan Berthoux, has demonstrated, in a US context, that switching 20% out of equities into housing assets in a conventional (60% equity, 40% bond) portfolio lowers annualised returns minimally, while sharply reducing volatility and maximum drawdowns over 6 and 12 months.

Analytical arguments for the protective attributes of real estate assets and statistical studies of long historical time series performance offer encouragement but fall short of the threshold of proof that real estate, and specifically residential housing assets, will prove a good inflation hedge over the next few years.

My expectation is that they will, provided that four conditions hold, to a greater or lesser degree.

First, that real interest rates remain very low, preferably negative. The public finances of most Western democracies have been wrecked by their responses to the pandemic. The restoration of some semblance of order in public finances requires that economic recovery boosts tax revenues and enables public supports to be withdrawn. The last thing that the UK – or US – government needs is a jump in borrowing costs. Policies of financial repression are likely to remain in force, notwithstanding the embarrassing resurgence of inflation.

Second, that the pace of wage inflation matches or exceeds that of consumer price inflation. Pleas for wage restraint from central bankers and politicians are likely to fall on deaf ears. The reality on the ground is that skill shortages abound, that an army of older workers has left the labour force during the pandemic and that large corporate profitability is extraordinarily strong. A little-understood aspect of the pandemic is that, for every £1bn added to the government’s budget deficit, about £300m ended up in corporate coffers. Companies are paying up for scarce staff because they can afford to do so.

Third, that risk assets suffer another price correction. The timing of the next equity market correction is anyone’s guess. However, the combination of historically high valuations – though possibly not quite as absurd as in 2000 – the threat to corporate profitability from escalating energy, materials and labour costs, geopolitical concerns and tightening credit conditions looks a potent concoction.

Fourth, that the real return on government and corporate bonds remains negative. This is the flipside of financial repression. For the government to stabilise its finances requires that its bond holders lose money in real terms. This has already started to happen, and the longer the duration of bonds held, the greater the likely erosion of the investment.

Are real estate assets the new bonds?